Sarcoidosis is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown etiology characterized by multi-organ involvement. End-organ disease consists of granulomatous inflammation, which if left untreated or not resolved spontaneously, leads to permanent fibrosis and end-organ dysfunction. Cardiac involvement and fibrosis in sarcoidosis occur in 5-10% of cases and is becoming increasingly diagnosed. This is due to increased clinical awareness among clinicians and new diagnostic modalities, since magnetic resonance imaging and positron-emission tomography are emerging as “gold standard” tools replacing endomyocardial biopsy. Despite this progress, isolated cardiac sarcoidosis is difficult to differentiate from other causes of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Cardiac fibrosis leads to congestive heart failure, arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Immunosuppressives (mostly corticosteroids) are used for the treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis. Implantable devices like a cardioverter-defibrillator may be warranted in order to prevent sudden cardiac death. In this article current trends in the pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of cardiac sarcoidosis will be reviewed focusing on published research and latest guidelines. Lastly, a management algorithm is proposed.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease of unknown etiology manifesting frequently as a mild or even asymptomatic pulmonary disease (Costabel, 2001; Yamamoto et al., 1992). Despite its generally benign nature, sarcoidosis may progress to organ fibrosis and impairment with poor prognosis including death (Swigris et al., 2011; Viskum and Vestbo, 1993). The first case of heart involvement in sarcoidosis was reported by Bernstein in 1929 in a 52-year-old tailor dying from heart failure (Bernstein, 1929). Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is considered to be the second most common cause of death in sarcoidosis patients globally and the first among Japanese sarcoidosis patients (Iwai et al., 1994). The pathology consists of granulomatous inflammation of the pericardium, myocardium and endocardium with patchy, multifocal involvement (Roberts et al., 1977). Clinically manifest CS occurs in 3-10% of patients with sarcoidosis in America and Europe, though its prevalence from certain autopsy studies is estimated to be up to 25% (Iwai et al., 1993; Perry and Vuitch, 1995; Silverman et al., 1978). CS manifests with ventricular arrhythmia, high grade block, sudden death or symptoms of heart failure most commonly presented with a rather acute onset (Birnie et al., 2016). In certain studies, almost one third of patients with CS did not have a diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis (Nery et al., 2014a; Tung et al., 2015). The diagnosis of CS remains a challenge, although the evolution of modern imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET), as well as the application of clinical guidelines have led to increased diagnosis rates (Birnie et al., 2014; Mc Ardle et al., 2013). Recognition of patients who will need an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator is paramount. Corticosteroids are considered the standard of care for CS treatment, though there is no consensus regarding the dosage or the duration of treatment and the role of second line steroid-sparing agents (Nagai et al., 2015; Yazaki et al., 2001).

Epidemiological studies have added to our knowledge about sarcoidosis and its phenotypes, though accurately estimating the incidence and prevalence of the disease is challenging due to its considerable heterogeneity (Hunninghake et al., 1999). Most studies suggest an annual incidence of 1-30 per 100,000 (Arkema and Cozier, 2018; Ungprasert et al., 2016a), with the highest prevalence reported in Scandinavian countries and United States (US) African-Americans, and the lowest among Asians (James and Hosoda, 1994; Morimoto et al., 2008). In most but not all studies, sarcoidosis is found more common in women (Byg et al., 2003; Deubelbeiss et al., 2010; Erdal et al., 2012; Gribbin et al., 2006; Henke et al., 1986; Hillerdal et al., 1984; Parkes et al., 1985; Rybicki et al., 1997; Thomeer et al., 2001; Ungprasert et al., 2016b). Peak onset age is between 20 and 40 years old and a second peak is seen especially in women over 50 years old (Kowalska et al., 2014; Selroos, 1969). An increase in the mean age at diagnosis has been reported the last twenty years (Foreman et al., 2006; Sawahata et al., 2015). Sarcoidosis is generally considered a benign disease with an annual rate of mortality in USA estimated between 2-4 deaths per million (Gerke, 2014; Mirsaeidi et al., 2015). African Americans experience more multiorgan involvement, and notably, African American women die at a younger age than Caucasians (Cozier et al., 2011). A lower socioeconomic status has been associated with more severe disease and new organs involved (Rabin et al., 2001; Rabin, 2004). The prevalence of CS is not exactly recognized. As mentioned above, clinically evident CS has been noted in 3% to 10% of patients, although autopsy studies reported cardiac involvement in about one-fourth of cases in the United States , in Europe and in Japan (Baughman et al., 2001; Greulich et al., 2013; James et al., 1976; Judson et al., 2012). More recent data suggest that cardiac involvement is more common in male sarcoidosis patients (Martusewicz-Boros et al., 2016a). CS incidence and hospitalizations have been rising, as a result of the increasing recognition and interest for the disease, the development of new imaging techniques, and the publication of related guidelines (Okumura et al., 2004; Patel et al., 2009; Soejima and Yada, 2009). Interestingly, the rates of in-hospital mortality between 2005 and 2014 have been found decreased in one study (Patel et al., 2018).

Significant research has not managed to establish a definite

etiology of sarcoidosis. Genetic, environmental, lifestyle and occupational risk

factors have been suggested, in order to explain the heterogeneity in disease

presentation and severity among different ethnic and racial groups (Abe et al., 1987; Berlin et al., 1997; Brennan et al., 1984; Cozier et al., 2012, 2013, 2015; Iannuzzi et al., 2007; Kucera et al., 2003; Martinetti et al., 1995; McGrath et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2004). The

general concept is of a gene-environment interaction, suggesting that sarcoidosis

results from the exposure of genetically susceptible individuals to specific

environmental agents (Chen and Moller, 2008; Verleden et al., 2001). The

human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, a group of related proteins that are

encoded by the major histocompatibility (MHC) gene complex in humans, has been

associated with sarcoidosis (Iannuzzi et al., 2007). The CD4

Clinical manifestations in sarcoidosis cohorts differ in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, type of onset and organ involvement (Cozier, 2016; Izumi, 1992; Jain et al., 2020; Lill et al., 2016; Loddenkemper et al., 1998; Pereira et al., 2014; Prasse et al., 2008; Siltzbach et al., 1974). Japanese patients are reported to have a much higher likelihood of ocular and cardiac disease than patients in the rest of the world, while uveitis and cutaneous involvement is more common in females than males (Birnbaum et al., 2011; Brito-Zerón et al., 2016; Pasadhika and Rosenbaum, 2015; Yanardag et al., 2003, 2013). Nevertheless, pulmonary disease is by far the most common organ involvement in sarcoidosis (Iannuzzi and Fontana, 2011; Neville et al., 1983; Rao and Dellaripa, 2013). Epidemiological studies have described the clinical heterogeneity of sarcoidosis highlighting the need for further clinical phenotyping – while a multidisciplinary approach should always be considered (Hattori et al., 2018; Judson et al., 2006; Kreider et al., 2005; Pietinalho et al., 1996; Reynolds, 2002; Rybicki and Iannuzzi, 2007). A large European multicenter study identified five CS-associated phenotype groups; cardiac involvement was part of the ocular-cardiac-cutaneous-central nervous system phenotype suggesting CS as a disease of the electrical conduction system of the heart (Schupp et al., 2018). In general, patients with cardiac sarcoidosis may have minimal extra cardiac disease or asymptomatic chest involvement (Nery et al., 2014b). Cardiac symptoms depend on the location, extent, and activity of the disease, and the most commonly observed manifestations are conduction abnormalities (including ventricular arrhythmias and atrio-ventricular blocks) and myocardiopathy leading to congestive heart failure (Terasaki et al., 2019). This is the case because the main cardiac compartments affected by CS are the intraventricular septum and the left ventricle myocardial wall, respectively.

Patients may present asymptomatically or experience palpitations,

syncope, or even sudden cardiac death. Ventricular arrhythmias such as premature

ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation

are caused by myocardial inflammation and fibrosis. Heart failure occurs as

inflammation and fibrosis progress, causing edema, cough and dyspnea that should

be differentiated from pulmonary disease. Decreased cardiac output may cause

oliguria, neurological signs, malaise, but also syncope, confusion, and decreased

levels of consciousness (Kandolin et al., 2011; Nery et al., 2013). Pulmonary

function testing may reveal obstructive and/or restrictive patterns as well as

TLCO (diffusing capacity of carbon monoxide) impairment. A recent study of 1,110

patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis reported that 10% of the cohort (25% of

which had an obstructive defect) had a mixed ventilatory defect. These patients

exhibited lower TLCO and suffered from stage IV sarcoidosis and higher mortality

compared to purely obstructive patients (Kouranos et al., 2020). Decreased

forced expiratory volume in 1

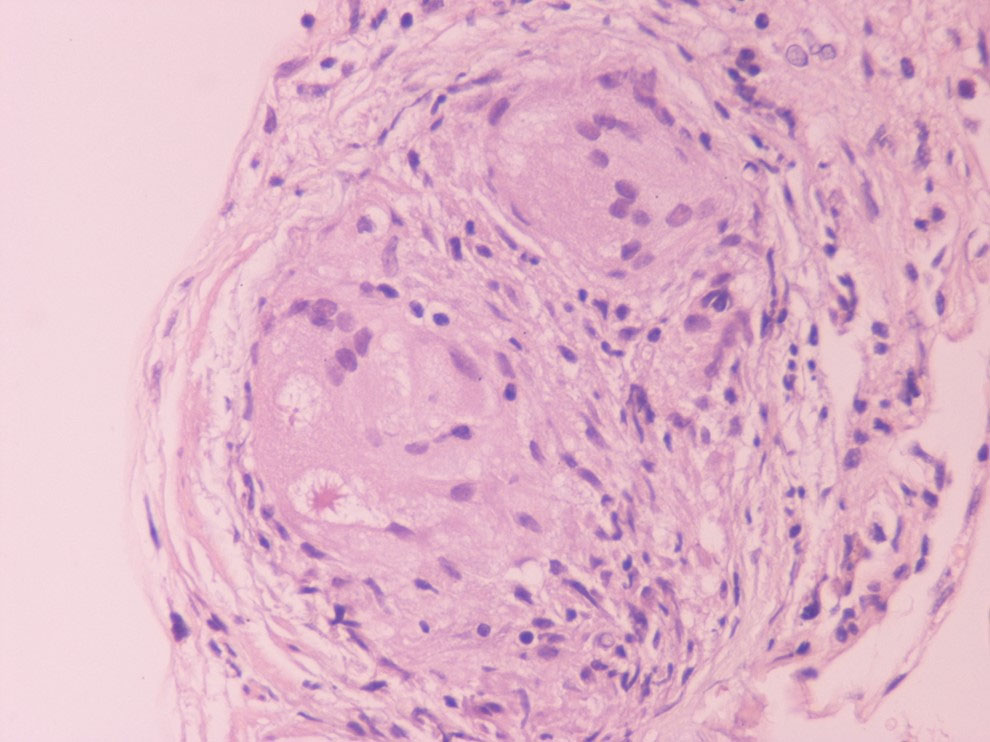

The incidence of progressive heart failure, arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) increases as CS becomes clinically recognizable; thus, early diagnosis and initiation of therapy is crucial to improve prognosis (Dubrey and Falk, 2010; Kim et al., 2009; Mantini et al., 2012; Pierre-Louis et al., 2009; Voortman et al., 2019). The classic triad of criteria establishing a diagnosis of sarcoidosis is 1) a compatible clinical and/or radiological picture; 2) histological evidence of noncaseating granulomas and 3) exclusion of other diseases (Costabel, 2001; Hunninghake et al., 1999). Diagnosis usually requires a multi-disciplinary approach, as almost any organ may be affected; sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, so establishing a CS diagnosis may be challenging (Bargagli and Prasse, 2018). Histological confirmation of CS cases is difficult, as endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) has low sensitivity (36%) due to the patchy nature of sarcoidosis and is also a procedure that is difficult to perform. Thus, cardiac sarcoidosis cannot be ruled out with a negative endomyocardial biopsy result (From et al., 2011; Uemura et al., 1999). Immunohistochemistry using anti-monoclonal antibody against P. acnes has even been suggested as a potential additive diagnostic tool given the low sensitivity of EMB (Asakawa et al., 2017). A more promising tool may be the recognition of increased lymphatic vessel counts on myocardial biopsy of CS subjects in the absence of granuloma, a finding that increases the sensitivity of EMB at 75% (Oe et al., 2019). Further, an immunohistochemical finding of increased dendritic cells along with decreased M2 among all macrophages in non-granulomatous sections of cardiac biopsy showed high specificity for cardiac sarcoidosis diagnosis, suggesting this phenotype as a histopathological surrogate for CS (Honda et al., 2016). A well-formed non-necrotizing granuloma in the heart is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.A well-formed non-necrotizing granuloma in the heart (Hematoxylin Eosin x400).

It is crucial for clinicians to screen for CS in all patients with extra cardiac sarcoidosis. Patients suspected of isolated CS without known sarcoidosis are less frequent; diagnosis in this case requires a high level of suspicion and exclusion of common diagnoses (mainly ischemic heart disease). The screening starts with a detailed history and physical examination and electrocardiogram (ECG) (Dubrey and Falk, 2010; Mantini et al., 2012). Patients with symptoms, an abnormal ECG, or cardiomegaly on chest x-ray without known risk factors should be referred for further testing. Transthoracic echocardiogram and 24h-holter monitoring may add additional information before the patient proceeds with subsequent advanced imaging (Kim et al., 2009). All patients with a pathologic ECG should be further investigated for CS, particularly those who experience clinical symptoms including palpitations, pre-syncope and syncope (From et al., 2011). Mehta et al. showed that the presence of cardiac symptoms (significant palpitations, syncope, or presyncope) and/or an abnormal cardiac test in known sarcoidosis patients had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 87% for CS diagnosis (Mehta et al., 2008). Despite this, the absence of cardiac related symptoms does not exclude the diagnosis of CS, and data on whether and when patients with a negative initial work-up should be rescreened, are lacking (Birnie et al., 2014). Male sex, cardiac-related symptoms, ECG changes, serum NT-proBNP level, multiorgan involvement, and radiological pulmonary progression have been suggested as potential risk factors for cardiac sarcoidosis development (Darlington et al., 2014; Youssef et al., 2011).

The electrocardiogram (ECG) result is usually abnormal in patients with clinically evident disease and mostly normal in clinically silent CS. Abnormalities include various degrees of conduction block, such as isolated bundle branch block and fascicular block. Furthermore, QRS complex fragmentation, pathological Q waves (pseudo infarct pattern), ST changes and (rarely) epsilon waves can occur. These ECG findings in patients with extra cardiac sarcoidosis warrant further imaging studies to rule out cardiac sarcoidosis, with which they have shown significant association (Martusewicz-Boros et al., 2016b). Some patients are diagnosed with abnormal ECG features years after the onset of non-cardiac sarcoidosis; thus, ECG is essential for long-term follow-up. Other possible signals might be baseline heart rate and PR interval. Signal averaged ECG and Holter monitoring revealing late potentials might predict cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis (Yodogawa et al., 2018). Most studies show that Holter monitoring can be a predictor of cardiac involvement with sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 21% (Freeman et al., 2013). Holter is also useful to monitor response to treatment with immune-suppressives in conductive abnormalities in serial fashion (Padala et al., 2017). The exact place of Holter monitoring in the screening for CS is not clearly defined; however, it is certainly a comfortable, out-patient assessment follow-up tool in patients suspected of or diagnosed with CS.

Similar to ECG, the trans-thoracic echocardiogram (TTE) result is oftenabnormal in manifested disease and normal in clinically silent CS (Kim et al., 2009). Though not pathognomonic, some findings are accepted as major and minor criteria in various diagnostic guidelines (Birnie et al., 2014; Hiraga et al., 1993; Judson et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2009; Terasaki et al., 2019). Echocardiography is not useful in screening for CS, due to its low sensitivity, around 25% in most studies (Kouranos et al., 2017). The most characteristic abnormality is basal interventricular thinning, and less often myocardial wall thickness, isolated wall motion abnormalities, LV and/or RV diastolic and systolic dysfunction and aneurysms are detected (Agarwal et al., 2014; Skold et al., 2002; Burstow et al., 1989; Sun et al., 2011). Newer techniques, including strain rate, might improve echocardiography sensitivity in CS diagnosis (Joyce et al., 2015; Murtagh et al., 2016).

Most biomarkers such as angiotensin-converting enzyme, neopterin

and troponin are elevated in patients with sarcoidosis; however, they lack

sensitivity and specificity and may be affected by concomitant drugs administered

(d’Alessandro et al., 2020; Kandolin et al., 2015; Vorselaars et al., 2015).

Hypercalciuria, increased serum chitotriosidase and BAL biomarkers (elevated

CD4

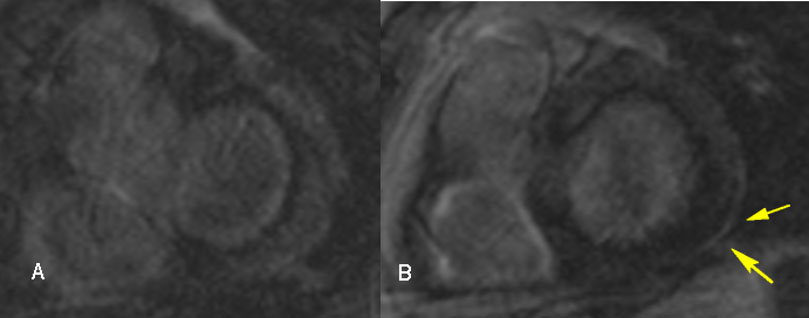

Recent studies have focused on the diagnostic and prognostic value of advanced cardiac imaging, trying to overcome the limitations of the aforementioned exams, in order to achieve an earlier diagnosis, at less advanced stages of the disease (Cheong et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009; Patel et al., 2009). CMR showing late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) is regarded as the study of choice for diagnosing cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis (Smedema et al., 2005). Apart from LGE, CMR may detect morphologic abnormalities (such as wall thinning and aneurysms) and functional parameters of cardiac chambers (LV and RV). LGE most commonly represents scar tissue, although inflammation may sometimes lead to extracellular expansion leading to LGE. In a study of 321 biopsy-proven sarcoidosis patients, CMR allowed the diagnosis of 44 patients with normal echocardiograms, as well as 15 asymptomatic patients. LGE may independently predict future adverse events, such as atrioventricular block (AVB), ventricular tachycardia (VT), sudden cardiac death (SCD) and heart failure (Nadel et al., 2015). Association of LGE on CMR with adverse cardiac outcomes is shown in other studies as well (Ichinose et al., 2008; Nagai et al., 2014). There is often a multifocal distribution, although a pattern of enhancement is not pathognomonic for CS (Cummings et al., 2009). LGE is mostly seen in basal segments, particularly of the septum and lateral wall, and usually in the midmyocardium and sub-epicardium (non-infarct pattern) as opposed to sub-endocardial scarring in the event of myocardial infarction. Few studies have focused on right ventricular involvement, suggesting that the RV free wall may also be involved in predicting adverse outcomes, particularly ventricular tachyarrhythmias (Crawford et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2011). The presence of LGE in patients with normal or near-normal LVEF greatly increases the likelihood of adverse events (Agoston-Coldea et al., 2016; Coleman et al., 2017; Ekström et al., 2016; Ise et al., 2014; Murtagh et al., 2016; Shafee et al., 2012; Yasuda et al., 2016). Remarkably, CMR identifies small regions of myocardial damage in subjects with preserved LV systolic function, allowing detection of “silent” CS (Pizarro et al., 2016). Interestingly, involvement of the RV in addition to the LV increases the risk of worse outcomes and all-cause mortality (Smedema et al., 2017). CMR with LGE is less sensitive regarding active myocardial inflammation; consequently, it may not properly guide immunosuppressive therapy. Moreover, CMR is not useful for extra-cardiac sarcoidosis compared to CT and PET-CT. Novel CMR techniques utilizing T1 and T2 mapping may allow detection of myocardial inflammation, suggesting a role in monitoring response to treatment (Crouser et al., 2014; Puntmann et al., 2017). The main value of CMR in the diagnostic algorithm of CS is its high negative predictive value, which exceeds 90% (Cheong et al., 2009). Representative CMR images of cardiac sarcoidosis are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Cardiac magnetic resonance images in a 54-year-old male with cardiac sarcoidosis, showing late gadolinium enhancement in the posterior-lateral left ventricle wall sub-epicardially (B, yellow arrows).

Neither CMR nor PET alone are positive in all CS cases. This is why when CMR is found normal – or is not available – further investigation with PET is warranted. Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) is a glucose analog that is useful in differentiating between normal and active inflammatory lesions (Pellegrino et al., 2005). In contrast to CMR which detects scar tissue, PET recognizes myocardial inflammation. FDG-PET testing should be performed at experienced centers (Birnie et al., 2014). Its use in assessing cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis requires extensive pre-imaging preparation to suppress physiologic glucose uptake by normal myocardium (Osborne et al., 2017). Although there are no specific imaging findings pathognomonic for CS diagnosis, focal or focal-on diffuse FDG uptake patterns suggest active CS (Ishimaru et al., 2005; Youssef et al., 2012). PET alone compared to Japanese guidelines showed 89% sensitivity and 78% specificity in diagnosing CS (Ishimaru et al., 2005). The presence of FDG uptake and perfusion defects on PET is associated with higher risk of VT or death. RV involvement on PET scan may be a marker of severe disease, a finding observed in CMR studies as well. FDG uptake serves as an excellent tool for early diagnosis and guiding therapy with a follow up approximately every 6 months (Blankstein et al., 2014). Abnormal tracer accumulation, initially considered a minor criterion for diagnosis, is now upgraded as a major criterion for diagnosis in recently published Japanese guidelines (Chareonthaitawee et al., 2017; Kumita et al., 2019; Terasaki and Yoshinaga, 2017; Wicks et al., 2018).

Given the high negative predictive value of CMR and the likelihood of 10-20% of false negatives with PET, CMR is given priority as initial diagnostic modality when CS is suspected in patients without contraindications for CMR testing. In a position statement, Slart et al. recommend the addition of FDG-PET to increase the diagnostic accuracy of CMR when disease is highly suspected (Slart et al., 2017). CMR and PET are therefore rather complementary, enabling imaging of the 2 different stages of the disease (i.e., fibrosis and inflammation); combination of the data is encouraged, especially if one of the tests yields inconclusive results (White et al., 2013). It should be noted that when CMR and/or PET reveal regional myocardial anomalies that may be due to sarcoidosis or atherosclerotic coronary artery disease, coronary angiography may be necessary to exclude significant coronary artery defects.

Three major guidelines exist for the diagnosis of CS. The first is the WASOG organ assessment tool published in 2014 and updated in the recent American Thoracic Society guidelines for sarcoidosis diagnosis (Crouser et al., 2020; Judson et al., 2014). The second is the HRS expert consensus statement in 2014 (Birnie et al., 2014) that suggested two diagnostic pathways: (a) histological diagnosis with the presence of noncaseating granulomas in myocardial tissue or (b) clinical diagnosis, as in histological diagnosis of extra cardiac sarcoidosis and one or more of the following clinical/imaging criteria: (1) cardiomyopathy and/or heart block, (2) unexplained sustained ventricular tachycardia, below 40%, (3) unexplained reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (4) Mobitz type II second-degree AV block or third-degree AV block, (5) late gadolinium enhancement on CMR in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis, (6) patchy uptake of cardiac FDG-PET in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis, or (7) positive gallium uptake in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis.

All of these criteria, as well as immunomodulatory treatment

responsive cardiomyopathy and/or AV block are considered features probable of

sarcoidosis and in particular cardiac involvement in ATS guidelines (Crouser et al., 2020). When these criteria are present in a patient with known extra

cardiac sarcoidosis, cardiac sarcoidosis is probable (

The third major guideline is the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare guidelines, initially described in 1993 and updated in 2017 with the following significant changes: (1) allowing diagnosis of isolated CS without a positive endomyocardial biopsy, (2) adding ventricular arrhythmia to the major criteria along with high-grade atrioventricular block and (3) moving abnormal ventricular wall anatomy, elevated myocardial uptake with FDG-PET and late gadolinium-enhanced CMR imaging to major criteria (Hiraga et al., 1993; Terasaki et al., 2019). Most recently, the Japanese Society of Nuclear Cardiology updated the recommendations regarding the 18FDG PET/CT use in diagnosis of CS (Ishimaru et al., 2005). The Japanese criteria may reflect the increased incidence of CS and its implications in Japan.

The latest ATS sarcoidosis guidelines recommend screening for cardiac sarcoidosis based solely on symptoms or signs and ECG, considering TTE and 24-hour Holter monitoring only in selected cases (conditional recommendation with low quality evidence). Patients with suspected cardiac involvement should undergo initial investigation with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, and/or PET when CMR is not available, to obtain diagnostic and prognostic information (Crouser et al., 2020). Major recommendations and guidelines are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

| 2016 JCS Guideline on Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiac Sarcoidosis | 2014 HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis |

| • Histological diagnosis | • Histological diagnosis |

| • Clinical diagnosis group when | |

| A. Epithelioid granulomas are found in organs other than the heart, and two or more major criteria or one major and two or more minor criteria | • Clinical diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis (probable CS) meaning histological diagnosis of extra cardiac sarcoidosis, exclusion of other diagnoses and one or more of |

| Major criteria | |

| 1. High-grade atrioventricular block (including complete atrioventricular block) or fatal ventricular arrhythmia (e.g., sustained ventricular tachycardia, and ventricular fibrillation) | 1. cardiomyopathy and/or heart block unexplained reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of less than 40% |

| 2. Basal thinning of the ventricular septum or abnormal ventricular wall anatomy (ventricular aneurysm, thinning of the middle or upper ventricular septum, regional ventricular wall thickening) | 2. unexplained sustained (spontaneous or induced) ventricular tachycardia |

| 3. Left ventricular contractile dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction less than 50%) or focal ventricular wall asynergy | |

| 4. 67Ga citrate scintigraphy or FDG PET reveals abnormally high tracer accumulation in the heart | 3. Mobitz type II second-degree AV block or third-degree AV block |

| 5. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI reveals delayed contrast enhancement of the myocardium | |

| Minor criteria | |

| 1. Abnormal ECG findings: Ventricular arrhythmias (nonsustained ventricular tachycardia, multifocal or frequent premature ventricular contractions), bundle branch block, axis deviation, or abnormal Q waves | 4. patchy uptake of cardiac FDG-PET in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis |

| 2. Perfusion defects on myocardial perfusion scintigraphy (SPECT) | 5. late gadolinium enhancement on CMRI in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis |

| 3. Endomyocardial biopsy: Monocyte infiltration and moderate or severe myocardial interstitial fibrosis | |

| 4. When the patient shows clinical findings strongly suggestive of pulmonary or ophthalmic sarcoidosis; at least 2 of the five characteristic laboratory findings of sarcoidosis and clinical findings strongly suggest cardiac involvement | 6. positive gallium uptake in a pattern consistent with cardiac sarcoidosis |

| 2014 The WASOG Sarcoidosis Organ Assessment Instrument | 2020 Diagnosis and Detection of SarcoidosisAn Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline |

| Probable criteria | Probable criteria |

| 1. Treatment responsive Cardiomyopathy or atrioventricular nodal block | 1. Treatment-responsive CM or AVNB |

| 2. Reduced LVEF in the absence of other clinical risk factors | 2. Reduced LVEF with no risk factors (echo and MRI) |

| 3. Spontaneous or inducible sustained VT with no other risk factor | 3. Spontaneous/inducible VT with no risk factors |

| 4. Mobitz type II or 3rd degree heart block | 4. New-onset, third-degree AV block in young or middle-aged adults |

| 5. Patchy uptake on dedicated cardiac PET | 5. Increased inflammatory activity in heart (MRI, PET, and gallium) |

| 6. Delayed enhancement on CMR | |

| 7. Positive gallium uptake | |

| 8. Defect on perfusion scintigraphy or SPECT scan | |

| 9. T2 prolongation on CMR | |

| (FDG) PET = (Fluorodeoxyglucose) positron emission tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; ECG = electrocardiogram; SPECT = Single-photon emission computed tomography; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; VT = ventricular tachycardia; CM = cardiomyopathy; AVNB = atrioventricular node block; AV = atrioventricular | |

When cardiac sarcoidosis is diagnosed or suspected without systemic sarcoidosis diagnosis, the term isolated cardiac sarcoidosis is used (ICS). Since established criteria for diagnosing CS require either extra-cardiac biopsy confirmation or EMB confirmation (a method of limited sensitivity as already shown), the diagnosis of ICS represents a true clinical challenge. Previous reports describe ICS as responsible for 25-65% of total CS (Kandolin et al., 2015; Okada et al., 2018). More recent data using FDG-PET report a more modest prevalence for ICS (9% of total) (Giudicatti et al., 2020). Scarce data indicate that ICS presents with lower LVEF, more frequent VTs, and necessitate ICDs more frequently than CS with systemic sarcoidosis (Kron et al., 2015; Okada et al., 2018).

ICS is rarely diagnosed compared to other causes of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM), often in cardiac explants post-transplant (Chang et al., 2012). Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is an inherited disease caused by mutations in desmosome encoding genes. Although HRS 2019 guidelines have established criteria for ARVC diagnosis (inverted T and epsilon waves on ECG, myocardial biopsy with decreased myocytes, VT‘s of LBBB, CMR features and family history, among others), confusion with ICS still occurs (Towbin et al., 2019). Electrophysiology studies have shown that reduced LVEF, a significantly wider QRS, right-sided apical VT, and more inducible forms of monomorphic VT are mainly encountered in ICS (Dechering et al., 2013). Differential diagnosis between ICS and ARVC may only partly be aided by modern diagnostic modalities, as shown in small cohorts (Steckman et al., 2012). Left ventricle scar on CMR points to ICS, while solely RV fibrosis points to ARVC, although both of these clues are not pathognomonic (Macias et al., 2014). The FDG-PET CT scan may test positive in ARVC as well as in ICS, as shown by Protonotarios et al (Protonotarios et al., 2019). Hoogendoorn et al. applied electroanatomical voltage mapping in order to characterize RV scar characteristics and distribution in ICS and ARVC. The authors validated their results in a separate CS population with excellent sensitivity and specificity (Hoogendoorn et al., 2020). Undiagnosed ICS may warrant ICD placement or transplant, as in other causes of ACM. An algorithm including CMR, FDG-PET, electroanatomic mapping (and guided-EMB) in experienced centers may facilitate the diagnosis of ICS in the near future (Muser et al., 2018).

In CS, clinicians first need to answer the key question whether the disease is only myocardial or affects the conduction system. Secondly, the initiating dose of corticosteroids is significantly lower than the one originally administered a few decades ago. Thirdly, it remains questionable whether asymptomatic patients should be treated, since reducing the risk of future adverse events should be weighed along with the treatment’s side effects (Patel et al., 2009). There is a lack of evidence whether treatment should be started at the presence of active lesions or the presence of clinical symptomatology (Birnie et al., 2014; Soejima and Yada, 2009). Many experts recommend treatment of asymptomatic patients, to prevent disease progression to fibrosis (Doughan and Williams, 2006; Ohira et al., 2008; Orii et al., 2015; Shafee et al., 2012).

Corticosteroids have been used for decades as first line treatment

of cardiac sarcoidosis (Aryal and Nathan, 2019; Grutters and van den Bosch, 2006). Steroid-sparing immunomodulators have been used or tested as second line

treatment for refractory disease. A large international multicenter registry

found that 26.4% of CS patients were on steroids alone, 22.6% were on steroids

and a steroid-sparing agent, and 9.7% were on steroid-sparing agent alone, with

methotrexate being the first steroid-sparing choice (Kron et al., 2017).

Retrospective studies have shown that corticosteroid treatment led to a reduction

in VT, reversal of atrioventricular block, improvement in left ventricular

ejection fraction and survival benefit (Banba et al., 2007; Furushima et al., 2004; Hulten et al., 2016; Kusano, 2013; Stees et al., 2011). Corticosteroid

therapy in cardiac sarcoidosis is mainly responsible for an improvement in

ejection fraction in patients with mild to moderate LV dysfunction, or in

patients with severe dysfunction and LVEF

Long-term use of high doses of corticosteroids adversely affects

patients’ quality of life and has been associated with life-threatening side

effects (Baughman et al., 2006; Cox et al., 2004; Nagai et al., 2014; Uthman et al., 2007). A prednisone dose of 40mg daily appears to be as effective and less

toxic than higher doses administered in the past. A commonly used initial dose

for those receiving prednisone only is 40mg daily, while for those patients

receiving an additional immunosuppressive agent, the initial dose is often

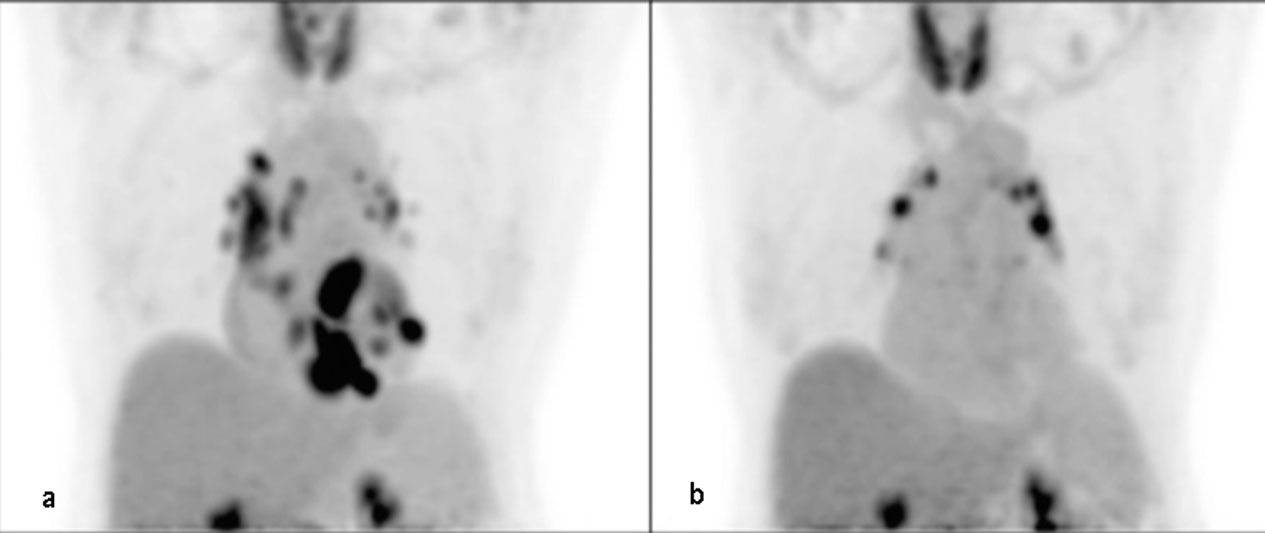

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.FDG-PET of a 63-year-old female on methotrexate for cardiac sarcoidosis before (a) and during (b) therapy with methotrexate for 2 years, exhibiting a significant decrease in FDG uptake in the heart suggesting adequate response to therapy. The scan continues to show FDG uptake in mediastinal lymph nodes (Bremer et al., 2018)

| Authors | Number of patients | Year of study | High dose Immunosuppresion | Tapering | Low dose Immunosuppresion |

| Yazaki et al., 2001 | 95 | 2001 | Prednisone 30-60 mg/d | Variable | Prednisone 5 to 15 mg/d |

| Chapelon-Abric et al., 2004 | 41 | 2004 | IV prednisolone 15mg/kg × 3d | Variable | Not reported |

| Chiu et al., 2005 | 43 | 2005 | Prednisone 60 mg | 2 months | Prednisone 10 mg/ d |

| Nagai et al., 2014 | 17, 67 | 2014, 2015 | Prednisone 30 to 40 mg/d | Variable | Prednisolone 5 to 15 mg/d |

| Ballul et al., 2019 | 36 | 2016 | Prednisone 60 mg/d | Not reported | Not reported |

| Fussner et al., 2018 | 91 | 2018 | Prednisone 40-60 mg/d | Variable | Variable |

Corticosteroids and antiarrhythmic drugs are initiated together for VTs when active inflammation is evident (Jefic et al., 2009), while catheter ablation and cardioverter defibrillator implantation are suggested if VT cannot be controlled (Naruse et al., 2014; Segawa et al., 2016). Amiodarone and sotalol are classic choices, although VTs are frequently resistant. The potential side effects of amiodarone include pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis, so a long-term treatment is not indicated for young patients (Birnie et al., 2014). Ablation therapy can be an option in VTs refractory to medical therapy. Despite a successful ablation, the recurrence rate remains high, although the total arrythmia burden may be reduced in up to 88% of cases with few major procedure related complications (Muser et al., 2016; Okada et al., 2018; Papageorgiou et al., 2018). CMR and PET findings could help in selecting more suitable patients for ablation therapy (Sohn et al., 2018). Yalagudri et al. stratified sarcoidosis patients with unexplained VT by FDG-PET results. They found that patients with increased myocardial FDG uptake were treated with immunosuppression, antiarrhythmics, and received ICD placement. If they had recurrence and had increased myocardial FDG uptake on their repeat FDG-PET CT scan, their immunosuppression was intensified. Patients without myocardial FDG uptake on initial PET CT scan were treated with antiarrhythmics and ICD without immunosuppression; if they lacked good clinical response, they later underwent catheter ablation. 13/14 patients in the inflammation cohort remained free of VT at their last follow-up visit (mean 38.2 months). All 4 patients in the scar cohort, despite the use of ICD and antiarrhythmics, experienced VT recurrence and underwent catheter ablation (Yalagudri et al., 2017). This study illustrates the fact that myocardial disease is more responsive to immunosuppressive treatment while arrythmias, though also partially responsive, will need risk assessment and electrophysiology study for ICD placement. In a large series, all patients with atrioventricular block at presentation underwent device placement (Fussner et al., 2018). According to HRS statement, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) and cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (CRT-Ds) are the preferred options compared to conventional pacemakers for cardiac sarcoidosis patients presenting with heart block (Birnie et al., 2014). Heart transplantation is seldom indicated, but may be of use in young refractory cases with non-responsive ventricular tachycardia or severe heart failure (Fussner et al., 2018).

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is considered responsible for the

majority of deaths in cardiac sarcoidosis (Roberts et al., 1977). HRS 2014

guidelines highlight that in CS with conduction abnormalities, device

implantation and an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator are useful, along with

immunosuppression when 2

ICD is recommended in case of 1) spontaneous sustained ventricular

arrhythmias and 2) in cases of LVEF

Identifying patients at risk for SCD is difficult (Ekstrom et al., 2016; Mehta et al., 2011; Vignaux et al., 2002). CS patients who have had

sustained VT/ VF or LVEF

CS patients with AV block and preserved LV function are shown to carry a 9% risk of SCD and 24% risk of SCD/VT at 5 years (Nordenswan et al., 2018). This is in line with the above suggestion to implant an ICD when a pacemaker is recommended, even with preserved LVEF (Birnie et al., 2014). The 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline agreed with the recommendation for ICD implantation in cardiac sarcoidosis patients with an indication for pacing (Kusumoto et al., 2019). This recommendation includes patients with second- or third-degree AV block who are on antiarrhythmic or beta blocker therapy and immunosuppression.

EPS is recommended in relatively preserved LVEF. This is because it has not shown more predictive value than LVEF, whereas the inducibility of sustained ventricular arrhythmias is inversely correlated with LVEF (Aizer et al., 2005). We have already discussed the prognostic significance of CMR and PET on VAs, VTs, and SCD (Yasuda et al., 2016; Youssef et al., 2012).

A recent study showed that adverse cardiovascular events in cardiac

sarcoidosis (VA, SCD, and heart transplantation) occur even if LVEF is moderately

affected (Rosenthal et al., 2020). This is in accordance with other studies

showing that Electro-physiology study had good predictive value for future VA as

well in patients with LVEF

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Suggested management algorithm for patients with probable cardiac sarcoidosis. ATS, American thoracic society criteria, biopsy of extra cardiac site; ECG, electrocardiogram; CMR, cardiac magnetic resonance, PET, positron emission tomography; VA, ventricular arrythmias; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; EPS, electrophysiologic study; ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Cardiac sarcoidosis should be adequately recognized and treated in a timely fashion, since it represents the second most frequent cause of death from sarcoidosis. Cardiac sarcoidosis may be asymptomatic, present with conduction abnormalities/advanced blocks, tachyarrhythmias or heart failure, be the cause of sudden cardiac death, or be diagnosed post-mortem. The diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis has become significantly more facilitated in recent years, as new imaging modalities (CMR and FDG PET) obviate the need for endomyocardial biopsy and provide functional/prognostic information. Ischemic heart disease sometimes has to be excluded. Diagnosis of cardiac sarcoidosis isolated at the heart is puzzling, however. Treatment with corticosteroids as the gold standard is imperative.The recognition of patients in risk for arrhythmias is crucial; these latter may need further electrophysiological studies and device placement, with improved outcome. Monitoring of CS, diagnosing probable cases (especially of isolated cardiac sarcoidosis), and the management of clinically silent cases are issues that must be addressed in the future.

EM, AA, EA and IP equally contributed in drafting the manuscript.

We would like to express my gratitude to all those who helped me during the writing of this manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest statement.