Academic Editor: Takatoshi Kasai

Intravenous morphine is a controversial treatment for acute

heart failure (AHF). This study aimed to evaluate and compare the efficacy of

intravenous morphine treatment vs. no morphine treatment in AHF

patients. Relevant research conducted before June 2020 was retrieved from

electronic databases. One unpublished study of our own was also included. Studies

were eligible for inclusion if they compared AHF patients treated with

intravenous morphine and patients who did not receive morphine. This

meta-analysis included three propensity-matched cohorts and two

retrospective analyses, involving a total of 149,967 patients

(intravenous-morphine group, n = 22,072; no-morphine group, n = 127,895).

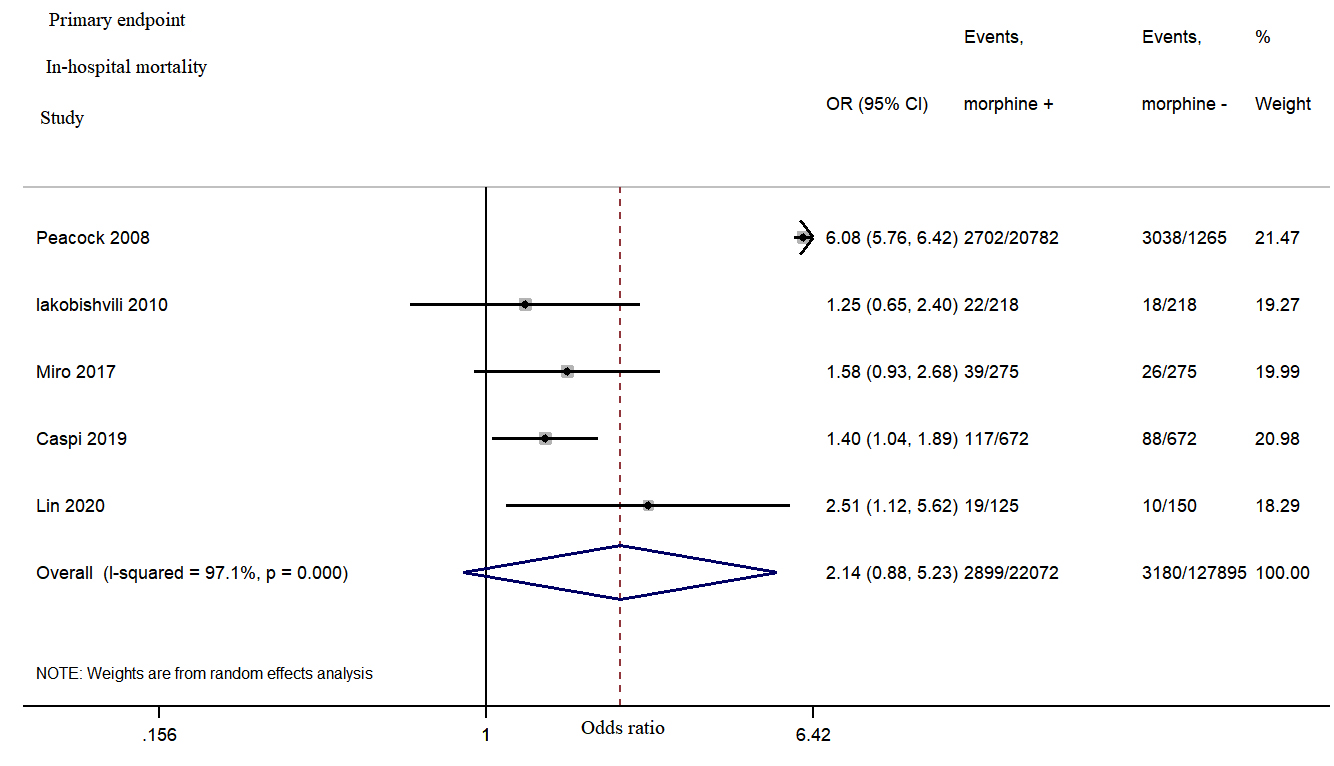

There was a non-significant increase in the in-hospital

mortality in the morphine group (combined odds ratio [OR] =

2.14, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.88–5.23, p = 0.095,

I

Acute heart failure (AHF) is defined as a sudden deterioration of cardiac function or the sudden onset of the symptoms and signs of heart failure [1]. AHF is a critical illness requiring prompt evaluation and treatment, as it typically leads to cardiogenic shock and is associated with a high risk of mortality [2]. For several decades, morphine has been recommended for the improvement of severe pulmonary edema in AHF based on a class-IIb level of evidence [3, 4]. However, intravenous morphine has been reported to produce adverse effects, such as nausea, hypotension, myocardial depression, and brainstem/respiratory center suppression (which increases the need for mechanical ventilation), in patients with AHF, thereby increasing the risk of poor clinical outcomes [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Although morphine has long been used to treat AHF patients, no consensus has yet been reached on the potential mortality risk of patients receiving morphine treatment.

Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis to evaluate and compare the clinical safety of intravenous morphine treatment in AHF patients.

We performed a comprehensive search of relevant publications in the following electronic databases: PubMed, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. We searched for studies conducted before June 2020. The following search terms were used: “intravenous morphine”, “morphine”, “opioids”, “acute heart failure”, “heart failure”, and “pulmonary edema”. In addition, we evaluated related publications, including review articles and editorials. One unpublished study of our own was also included in this meta-analysis. The present study was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42020207805).

Included papers required fulfillment of the following content criteria: (i)

patients with AHF, and (ii) intravenous morphine used in the

treatment group (dosage

The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. The secondary endpoints were need for invasive mechanical ventilation and long-term mortality with follow-up durations ranging from 30 days to 12 months. We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) to assess the risk of bias of the included studies. The Begg’s funnel plot was used to evaluate publication bias.

We used STATA software (version 14.0; StatCorp, College Station, TX, USA) to

conduct the meta-analysis. The primary endpoint (in-hospital mortality) and

secondary endpoints (invasive mechanical ventilation and long-term mortality)

were calculated as combined odds ratios (OR) or hazard ratios (HR) with 95%

confidence intervals (CIs). The I

Initial screening identified 722 related studies through the different search engines. Of these, we excluded 303 duplicated articles, 414 articles that did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, and 1 article that was not written in English. Thus, three propensity-matched cohorts [7, 8, 9] and one retrospective analysis [6] were included. Additionally, we included our own unpublished study, “Correlations between Morphine Use and Adverse Outcomes in Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction with Acute Heart Failure: a retrospective study” which was a retrospective analysis available as a preprint on Research Square [10]. Thus, finally, a total of 149,967 patients were included (intravenous-morphine group, n = 22,072; no-morphine group, n = 127,895) as seen in Fig. 1. All studies provided the primary clinical endpoints, and 4 studies provided the secondary endpoint; 3 studies had follow-up durations ranging from 30 days to 12 months (Table 1, Ref. [6, 7, 8, 9, 10]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flow chart of the study-selection processes.

| Study | Year | Design | Participants | Primary endpoint (in-hospital mortality) | Secondary endpoint | Follow-up |

| Peacock WF, et al. [6] | 2008 | Retrospective analysis | Acute decompensated heart failure | 2702 (13.0%) vs. 3038 (2.4%), p = 0.001 | Mechanical ventilation | - |

| (a) morphine group, n = 20,782; EF% 35 (22, 50) | 3200 (15.4%) vs. 3544 (2.8%), p | |||||

| (b) no-morphine group, n = 126,580; EF% 35 (23, 53) | ||||||

| Iakobishvili Z, et al. [7] | 2010 | Prospective heart failure survey (score-matching analysis) | Acute decompensated heart failure | 22 (11.5%) vs. 18 (8.3%), p = 0.55 | No data available | - |

| (a) morphine group, n = 218; EF% 35 (35, 42) | ||||||

| (b) no-morphine group, n = 218; EF% 35 (25, 50) | ||||||

| Miró O, et al. [8] | 2017 | Multicenter observational study (score-matching analysis) | Acute heart failure | 39 (14.2%) vs. 26 (9.1%), p = 0.083 | Mechanical ventilation | 30 days |

| (a) morphine group, n = 275; NYHA III–IV% 32.1 | 8 (2.9%) vs. 12 (4.4%) , p = 0.5 | |||||

| (b) no-morphine group, n = 275; NYHA III–IV% 33.5 | 30-day mortality | |||||

| OR = 1.66 (95% CI: 1.09–2.54) | ||||||

| Caspi O, et al. [9] | 2019 | Propensity matched cohort | Acute decompensated heart failure | 117 (17.4%) vs. 88 (13.4%), p = 0.083 | Mechanical ventilation | 12 months |

| (a) morphine group, n = 672 | 50 (7.4%) vs. 24 (3.6%), p = 0.003 | |||||

| (b) no-morphine group, n = 672 | 12-month mortality | |||||

| OR = 1.11 (95% CI: 0.93–1.33), p = 0.32 | ||||||

| Lin YW, et al. [10] | 2020 | Retrospective analysis | AMI with acute heart failure | 19 (15.2%) vs. 10 (6.67%), p = 0.035 | Mechanical ventilation | 12 months |

| (a) morphine group, n = 125; EF% 49.74 |

24 (19.2%) vs. 16 (10.67%), p = 0.031 | |||||

| (b) no-morphine group, n = 150; EF% 49.39 |

12-month mortality | |||||

| OR = 1.54 (95% CI: 0.55–4.3), p = 0.40 | ||||||

| AMI, acute myocardial infarction; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. | ||||||

There was a non-significant increase in the in-hospital

mortality in the morphine group (OR = 2.14, 95% CI: 0.88–5.23, p =

0.095, I

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Morphine use in acute heart failure was associated with a non-significant increase in the in-hospital mortality.

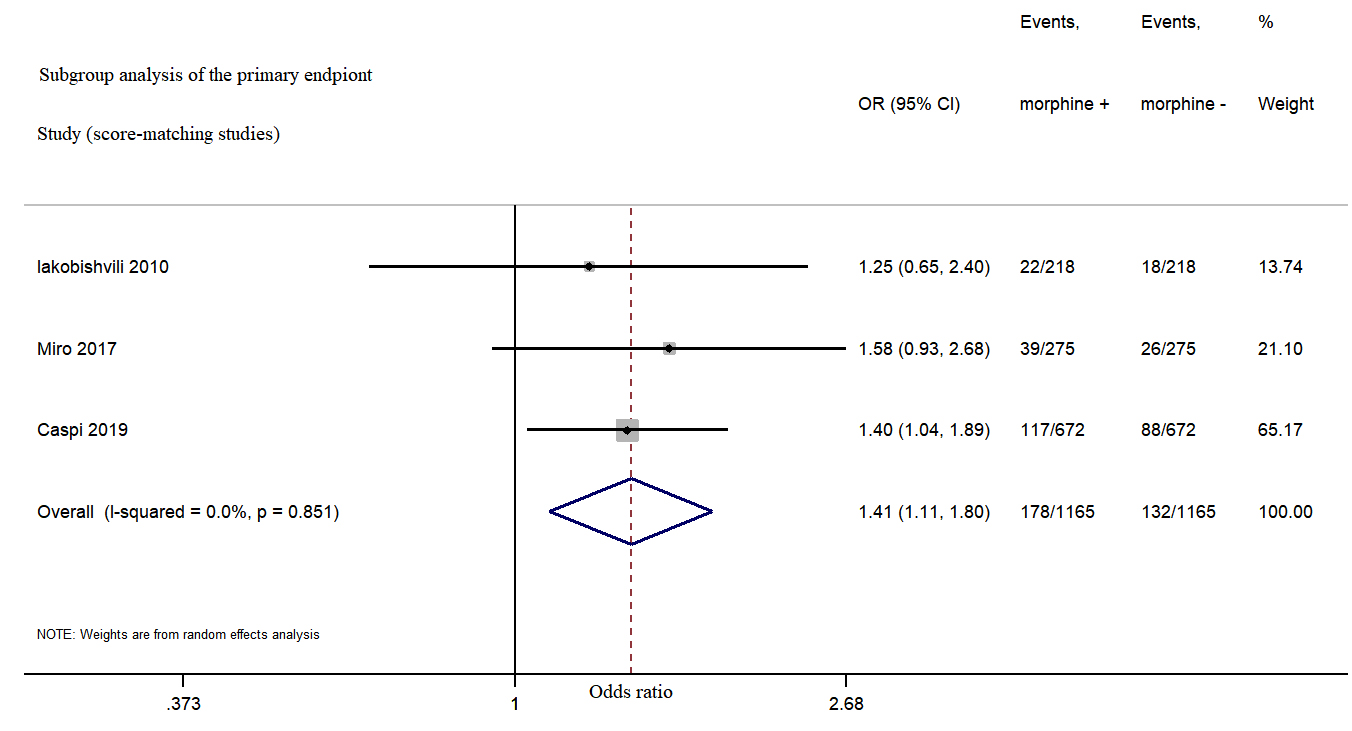

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Morphine use in acute heart failure increased in-hospital mortality from subgroup analysis.

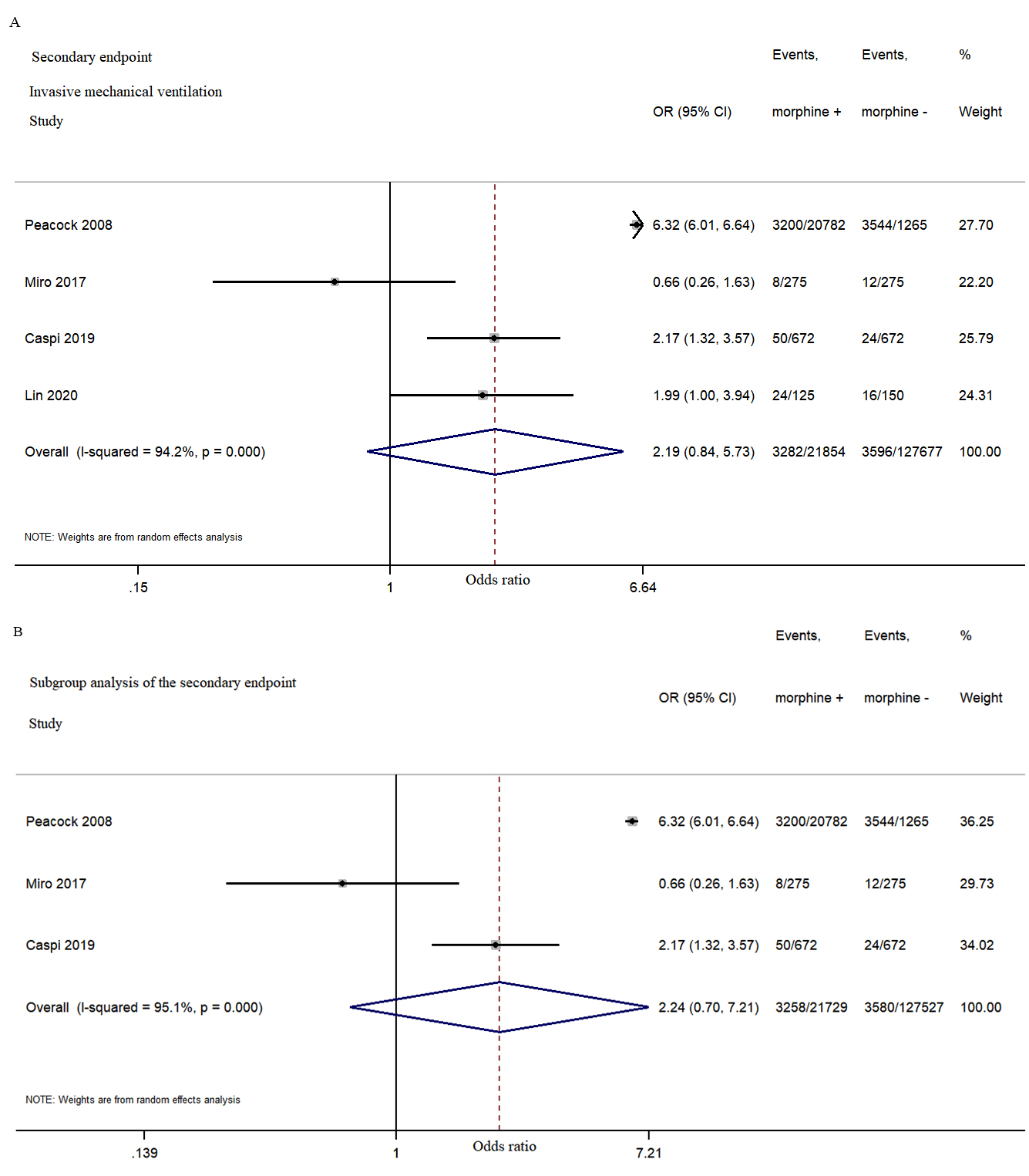

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Morphine use in acute heart failure did not significantly increased the rate of invasive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization. (A) The second endpoint study of invasive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization. (B) The subgroup analysis of the second endpoint.

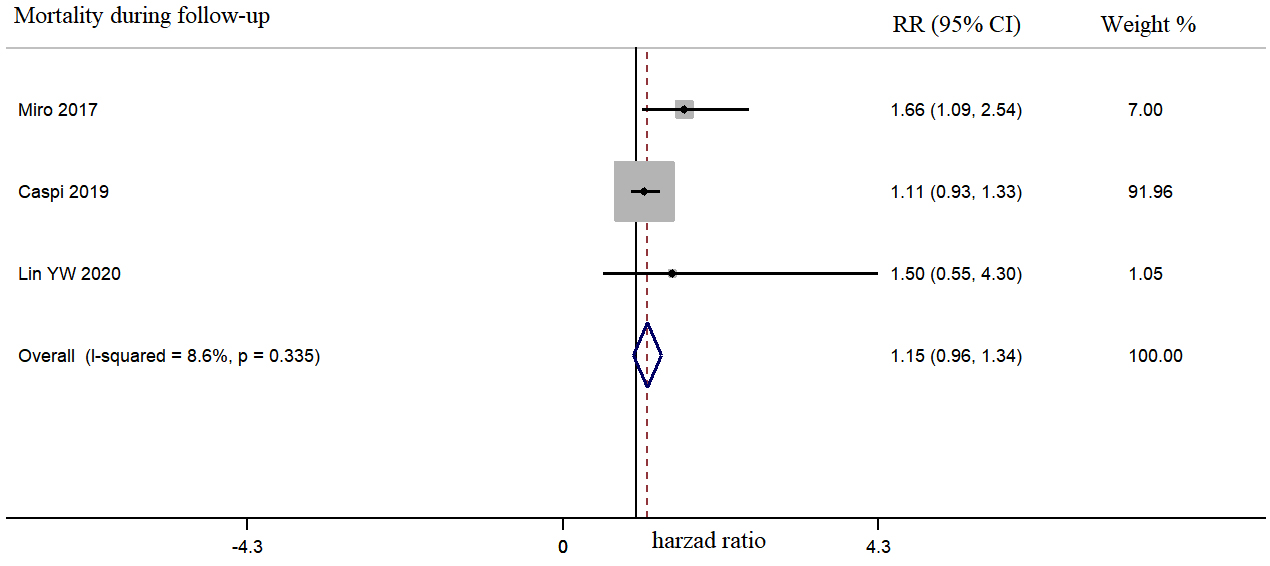

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Morphine use in acute heart failure was not associated with long-term mortality during a follow-up period of 30–365 days.

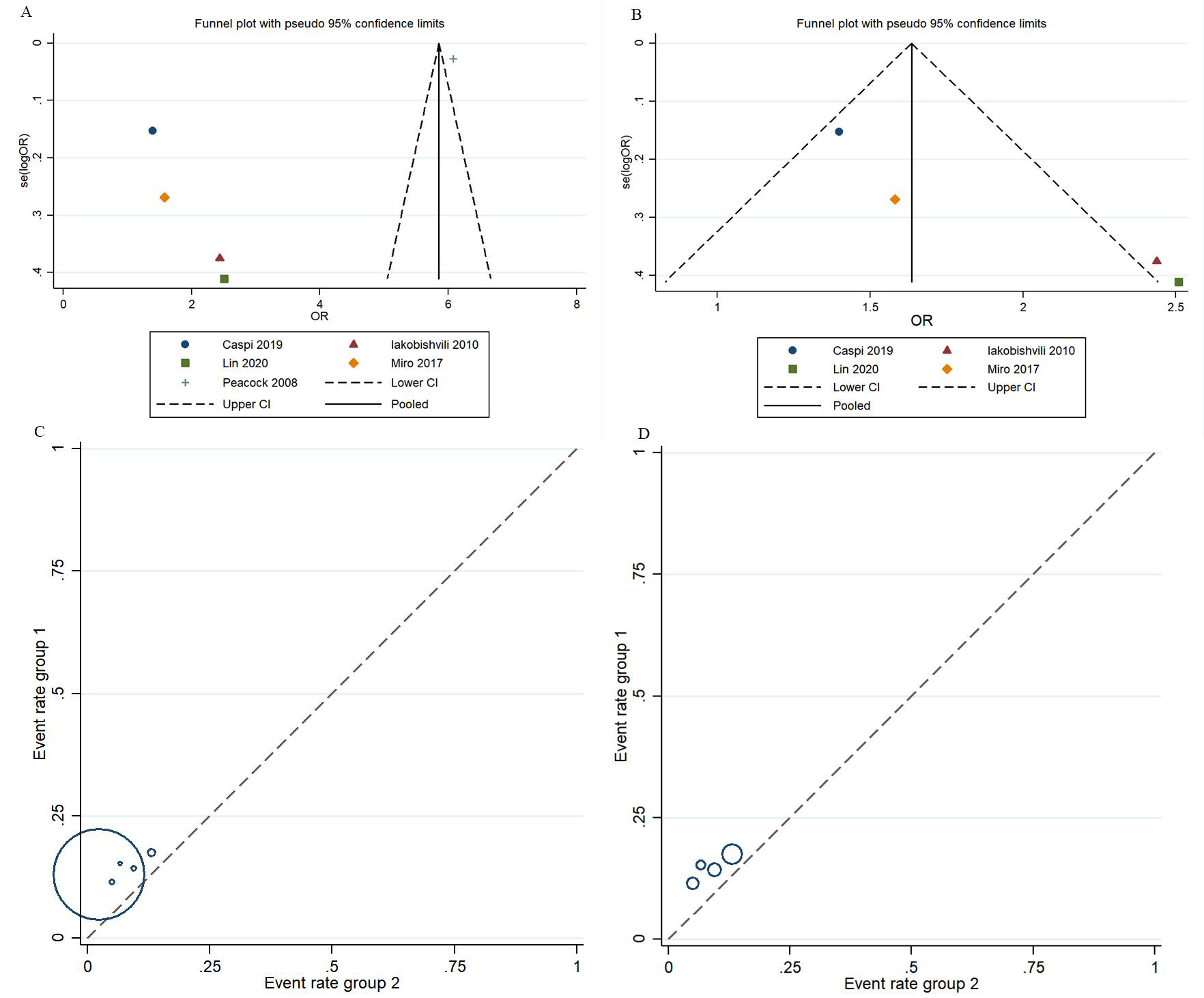

All included studies represented a low risk of bias in selective outcome

reporting and outcome assessment. The scores of NOS for study quality assessment

of included studies ranged from 7 to 9. However, the funnel plot asymmetry for in-hospital mortality and invasive mechanical ventilation indicated publication

bias (Fig. 6). Between-study heterogeneity in in-hospital

mortality was I

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.Assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies. (A,C) Public bias assessment for in-hospital mortality. (B,D) Public bias assessment for invasive mechanical ventilation.

This meta-analysis showed a trend for increased risk of in-hospital mortality in AHF patients who received intravenous morphine treatment as compared to AHF patients who were not treated with morphine from subgroup analysis.

Morphine can be a valuable treatment for AHF, especially in patients with acute pulmonary edema, because of its anti-anxiety, vasodilator, pain-relieving, and sedative properties [11]. However, the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology supports the use of morphine only for the palliative treatment of end-stage heart failure [12], while the European Society of Cardiology recommends the use of morphine only for patients with severe breathing difficulties or prominent pulmonary edema [2]. Morphine treatment in AHF has several potentially harmful effects, including vomiting (which leads to decreased drug absorption and an increased risk of apnea) [13], myocardial depression (which decreases the heart rate and cardiac output) [14, 15], respiratory depression (which increases the risk of invasive mechanical ventilation) [16, 17, 18], and attenuated platelet inhibition [19, 20, 21]. These adverse effects may increase the risk of death in patients receiving intravenous morphine.

Our meta-analysis showed a trend in the relationship between intravenous morphine treatment and in-hospital mortality in patients with AHF. Thus far, no randomized clinical trial has examined the benefit and safety of intravenous morphine in patients with AHF. In 2008, a review of five studies conducted between 1987 and 2003 showed that the use of morphine could worsen the condition of AHF patients [22]. Since then, the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) trial has shown that compared to no morphine treatment, the use of intravenous morphine in acute decompensated heart failure was independently associated with a higher risk of in-hospital death (13.00% vs. 2.40%, p = 0.001) [6]. However, Iakobishvili et al. [7] conducted propensity analysis and demonstrated that intravenous morphine was not associated with in-hospital death (OR = 1.2, p = 0.55), except in the case of patients with Killip class III–IV acute myocardial infarction (OR = 2.3, 95% CI: 1.5–3.5). Similar results were obtained using a propensity score-matched analysis based on the Epidemiology of Acute Heart Failure in Emergency Departments Registry. Specifically, the results showed that intravenous morphine treatment not only significantly increased in-hospital mortality (14.2% vs. 9.1%, OR = 1.65, p = 0.083), but was also significantly associated with 30-day mortality (20% vs. 12.7%, OR = 1.66, p = 0.017) in patients AHF [8]. These findings suggest that morphine treatment tended to aggravate adverse outcomes, but this result was not obvious. In a recent study by Caspi et al. [9], morphine administration was associated with in-hospital mortality (17.4% vs. 13.4%, OR = 1.43, p = 0.024) and showed a significant linear dose-response relationship with this outcome. The above results may be attributable to the adverse effects of intravenous morphine, which themselves depend on various factors such as morphine dosage, worse functional status, and advanced heart failure (New York Heart Association class III–IV).

Our analysis demonstrated that intravenous morphine was not positively correlated with an increased risk of invasive mechanical ventilation and long-time mortality. As significant heterogeneity persisted after subgroup analysis, it was not clear whether morphine use led to endotracheal intubation or whether invasive mechanical ventilation required morphine use as a sedative (the timing of morphine use was unclear in the ADHERE trial) [6]. However, other retrospective studies have reported that morphine use does increase the risk of endotracheal intubation [23].

Potential limitations of our meta-analysis should be considered. First, the included studies were real-world observational and retrospective studies. Therefore, in some studies, there were differences at baseline between the subjects who received morphine and those who did not. Accordingly, the subgroup analysis including score-matching studies was conducted to reduce the risk of selective bias and heterogeneity. Second, the subgroup analysis of dosage of morphine was unavailable, and the temporal relationship between morphine use and adverse reactions was unknown. Third, myocardial infarction can by itself portend risk of mortality and confuse research results. Finally, limited data on mechanical ventilation were included in the literature analyzed (only 4 studies measured invasive mechanical ventilation during hospitalization, and one of them was not published), and the causal relationship between morphine and mechanical ventilation remains unclear. These factors could have created additional heterogeneity. Despite the above limitations, we believe that our study strengths include our well-designed and strict systematic review methodology. Randomized controlled trials are required to further confirm these results.

The present study increases the awareness of the potential risk of mortality after intravenous morphine treatment in patients with AHF. Owing to the increased risk, routine use of morphine in AHF patients should involve a thoughtful discussion.

YWL, QLC and SHD designed, collected, analyzed and wrote this manuscript. JY, YC, HDL, SHD and XLP assisted in the conduct of study. QLC, and SHD was the principal investigator. JY, YC, HDL and XLP revised critically the paper and interpreted the data based on the study aims and statistical analysis. All authors read and approved this article for publication.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen People’s Hospital (SZLY2020034).

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

Supported by Shenzhen Key Medical Discipline Construction Fund (No. SZXK003 and No. SZXK059) and Sanming Project of Medicine in Shenzhen (No. SZSM201412012).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.