1 Department of Ultrasound, The First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, 150001 Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

2 Department of Interventional Radiology, Harbin Medical University Cancer Hospital, 150081 Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

3 Department of Radiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University, 150086 Harbin, Heilongjiang, China

Abstract

Ubiquitination plays a key role in various cancers, and F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7 (FBW7) is a tumor suppressor that targets several cancer-causing proteins for ubiquitination. This paper set out to pinpoint the role of FBW7 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

The target proteins of FBW7 and the expression of hromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 3 (CHD3) were analyzed in liver HCC (LIHC) samples using the BioSignal Data website. The effects of CHD3 and FBW7 on HCC cell viability, migration, invasion and stemness were investigated through cell counting kit (CCK)-8, wound healing, transwell and sphere formation assays. Detection on CHD3 and FBW7 expressions as well as their relationship was performed employing quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), immunoprecipitation, ubiquitination and western blot analyses.

The prediction of Ubibrowser revealed CHD3 as a target protein of FBW7. The data of starBase exhibited a higher expression level of CHD3 in LIHC samples relative to normal samples. CHD3 was upregulated in HCC cells. CHD3 knockdown inhibited HCC cell proliferation, migration, invasion, stemness and oxaliplatin sensitivity. FBW7 targeted CHD3 for ubiquitination. FBW7 overexpression restrained HCC cell migration, invasion and stemness, and attenuated the effects of overexpressed CHD3 on promoting migration, invasion, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance in HCC cells.

FBW7 overexpression suppresses HCC cell metastasis, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance via targeting CHD3 for ubiquitylation and degradation.

Keywords

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7

- chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 3

- ubiquitylation

- metastasis

- stemness

Resulting in more than 700,000 deaths per year, liver cancer ranks 5th in the most prevalent malignancies and 3rd in the cancer-related lethal factors globally, of which hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) as a subtype accounting for 80% of liver cancer cases worldwide in 2020 [1, 2, 3]. In recent years, HCC diagnosis and treatment benefit from the advancement of multimodal therapy, including liver transplantation, minimally invasive treatment and hepatectomy, with greatly improved overall therapeutic efficacy [4]. Nevertheless, most patients are diagnosed with middle and advanced HCC, for whom the tumor is not resectable and traditional chemotherapy/radiotherapy has limited benefit clinically, leading to a dismal prognosis and five-year survival rate below 10% [5, 6, 7]. Notably, because of the frequent recurrence and high metastasis of HCC [8], the molecular mechanisms are worthy of exploration. In addition, the epigenetics participate in cancer initiation through modulating the characteristics of stem cells [9, 10]. Therefore, we tried to explore the epigenetic mechanisms implicated in HCC, hoping to offer some helpful insights for HCC diagnosis and treatment.

As a modification at the post-translational level, ubiquitination extensively impacts different physiological processes, consisting of DNA damage response, cell proliferation, autophagy and apoptosis through diverse pathways [11]. Besides, the disorder of ubiquitination, which can cause the imbalance of cellular homeostasis, also influences multiple diseases containing cancers [12]. Hence, ubiquitination pathways are perceived as a potential therapeutic strategy for tumors. Ubiquitination is mediated via a cascade of three enzymes. Mechanically, ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1) ATP-dependently activates the ubiquitin (a protein consisting of 76-amino acids) which is then transferred to the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and in conjunction with the ubiquitin ligases (E3s) binding to specific proteins, thereby modifying the target molecules [13]. Belonging to the F-box protein family, F-box and WD repeat domain containing 7 (FBW7) is an E3 described as the substrate recognition element of the S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 (SKP1)-cullin 1 (CUL1)-F-box protein (SCF) ubiquitin ligase complex [14, 15]. FBW7 can attenuate tumor and target numerous oncogenic proteins for ubiquitination and degradation [16, 17]. Furthermore, FBW7 can repress HCC cell invasion, and control differentiation, multipotency, self-renewal and survival in varied stem cells, including those of the liver [18]. However, the regulation of FBW7 on ubiquitination during the development of HCC remains unknown.

Prediction of target proteins of FBW7 was completed by Ubibrowser (http://ubibrowser.ncpsb.org.cn/ubibrowser/). After logging in the website, the query protein was selected as E3, and the “FBW7” was input. Then the “Explore” button was clicked, “Continue” button was chosen, and results were obtained.

Analysis of chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 3 (CHD3) expression in 374 liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC) and 50 normal samples was conducted on starBase (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/), where we logged in, selected “Pan-Cancer”, clicked “Gene Differential Expression”, input “CHD3”, and chose “LIHC” to obtain results.

Culture (humidity, 95% air, 5% CO2, 37 °C) of HCC cell lines HCCLM3 (SCSP-5093, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai, China) and HepG2 (SCSP-510, Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai, China) as well as normal liver cell line HL-7702 (BFN608006124, Shanghai Cell Bank, Shanghai, China) was carried out with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; A4192101, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) incorporating 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, 16140063, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Mycoplasma tests were performed periodically by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to confirm that cells were not contaminated by mycoplasma, followed by authentication with short tandem repeat (STR) profiling.

Short hairpin RNA CHD3 (shCHD3)

(5′-CCCAGAAGAGGAUUUGUCA-3′) was constructed on shRNA plasmid DNA (SHC004,

Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany), while mammalian promoter plasmid

vector (PP2356, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany) was applied in the construction of

CHD3 overexpression plasmid and FBW7 overexpression plasmid

(their sequences are listed in Supplementary File 1), with the empty

shRNA plasmid and the empty mammalian promoter plasmid as the negative controls,

respectively. Besides, pCMV-N-Myc (D2756, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai,

China) and pUC-CMV-N-Flag (D2722, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) served

as the vectors of Myc-FBW7 as well as Flag-CHD3. pCMV-HA-ubiquitin (Ub) plasmid

was bought from Ke Lei Biological Technology (kl-zl-0513, Shanghai, China).

Transfection of above plasmids into HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells was accomplished

through Lipo 2000 (11668500, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Firstly, cells were trypsinized (15090046, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA,

USA), seeded in 24-well plates (1

Following total RNA obtainment from cells with TRIzol kit

(12183555,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and cDNA synthesis using

SuperScript™ First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (11904018,

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), cDNA amplification was

completed with TB Green® Fast qPCR Mix (RR430S, Takara Biomedical

Technology, Beijing, China) in a StepOnePlus PCR system (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) under the conditions of 1 cycle of predenaturation

(30 s, 95 °C) as well as 40 cycles (5 s, 95 °C; 15 s, 60

°C). Synthesis of primer sequences by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China) is

displayed in Table 1.

| Target gene | Primers, 5 | |

| CHD3 | ||

| (F) | CCCTCACTGTGAGAAGGAG | |

| (R) | CCTTCTTCCTCTCCCTCCT | |

| FBW7 | ||

| (F) | AAGAGTTGTTAGCGGTTCTC | |

| (R) | CTGGCCTGTCTCAATATCC | |

| (F) | GAAGATCAAGATCATTGCTCCTC | |

| (R) | ATCCACATCTGCTGGAAGG | |

Abbreviation: F, Forward; R, Reverse.

Based on CCK-8 kit (C0040, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), we examined cell viability and toxicity. For cell viability, transfected cells experienced digestion, seeding in 96-well plates (2000/well), and 24/48/72/96 h cultivation, followed by culture (1 h, 37 °C) in CCK-8 solution (10 µL/well).

For cell toxicity, 5000 cells in the exponential growth phase underwent 24-h incubation in a 96-well plate (100 µL/well). As mentioned before, oxaliplatin (OXA; MZ3501-500MG, Mocan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was prepared and diluted in sterile saline (0.9%) [20]. Subsequently, different concentrations of OXA (0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 µM) were sequentially cultivated with cells (37 °C, humidity, 5% CO2, 24 h). Then, cells were further immersed in 10 µL/well CCK-8 solution (1–2 h, 37 °C).

Measurement of optical density (OD) value (450 nm, an enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay reader) was followed by cell viability data obtained using

the equation: Cell viability (%) = (average OD value of experimental group –

average OD value of blank control group)/(average OD value of negative control

group – average OD value of blank control group)

Cells (5

Suspension of the digested and PBS-washed cells was performed in the serum-free

medium. Later, 2

Seeded at 2

Following cell centrifugation (4 °C, 12,830

HEK-293 cells (Procell Life Science&Technology, Wuhan, China) were cultivated in Minimum Essential Medium (PM150467, Procell Life Science&Technology, Wuhan, China) incorporating 1% P/S and 10% FBS.

To explore the interaction between exogenous FBW7 and exogenous CHD3, HEK-293 cells transfected with Myc-FBW7 and Flag-CHD3 expression vectors underwent lysis in RIPA lysis buffer. The lysates experienced culture (4 °C, overnight) with BeyoMag™ Anti-Myc or Anti-Flag Magnetic Beads (P2118, P2115; Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China). With the application of an immunoprecipitation kit (ab206996, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), HEK-293 cells were lysed, and precleared by Protein A/G Sepharose® beads. The lysates were cultured with antibodies against FBW7 (1:400) or CHD3 (1:50) at 4 °C with gentle rocking overnight, for which rabbit Immunoglobulin G (IgG) (A7016, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) was the negative control. Next, Protein A/G Sepharose® beads were mixed with the antigen-antibody complex (4 °C, 1 h) to acquire antigen-antibody-bead complex. As for ubiquitination detection, the lysates of HEK-293 cells with transfection of Myc-FBW7 expression vector, Flag-CHD3 expression vectors as well as HA-Ub and treatment of MG-132 (S1748, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) were cultivated (4 °C, overnight) with the antibody against ubiquitinylated proteins (1:2000; Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and BeyoMag™ Anti-Flag Magnetic Beads (P2115, Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China).

Subsequently, all bound proteins above were eluted with the beads, and rinsed off in the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and finally heated at 90 °C for 5 min. The protein level was obtained by western blot. Image J (1.48v, NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was employed to analyze the band intensities.

Statistical data (form: means

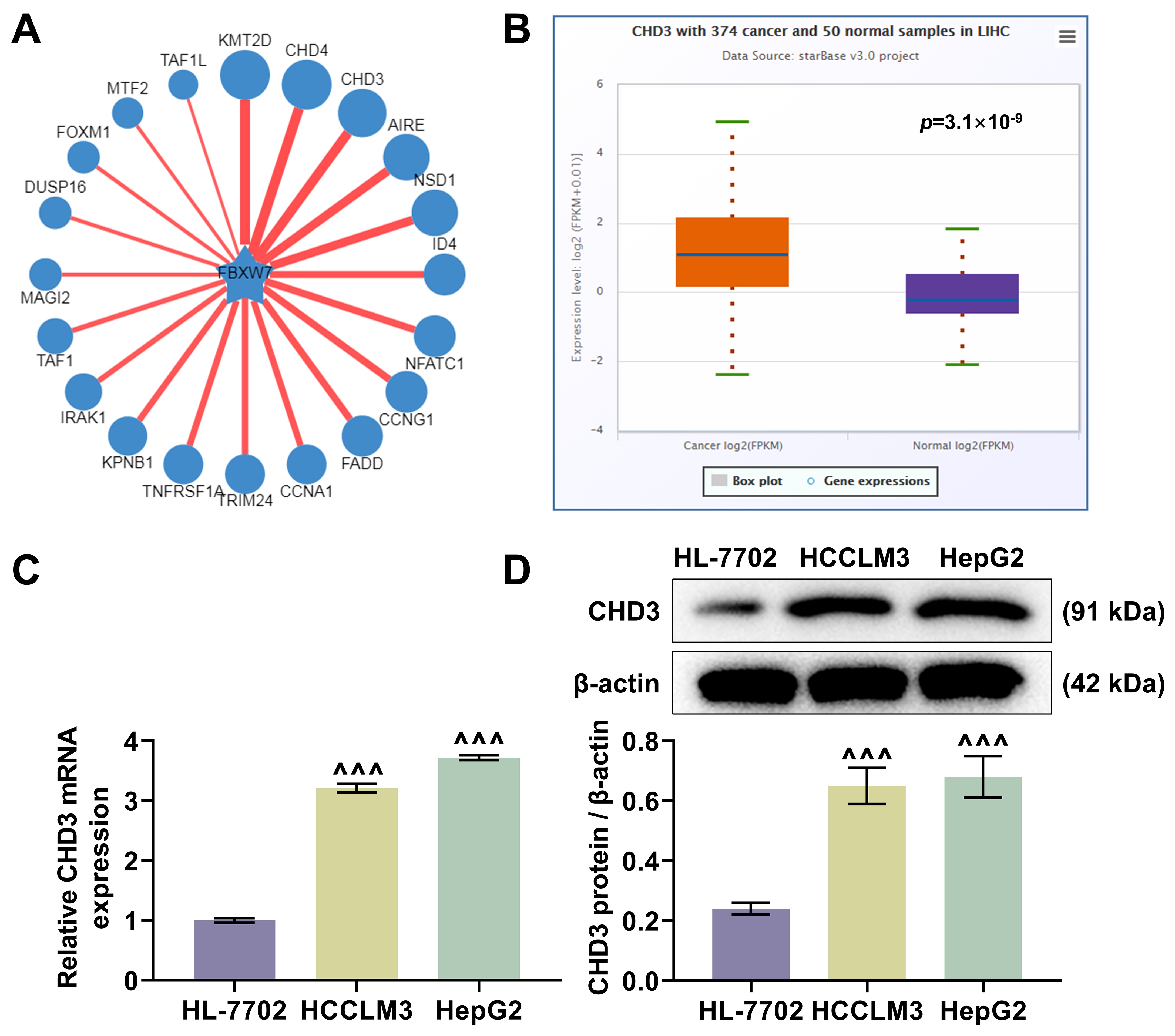

The ubibrowser predicted CHD3 as a target protein of FBW7 (Fig. 1A). The

analysis of starBase exhibited a higher expression level of CHD3 in LIHC

samples relative to normal samples (Fig. 1B, p = 3.1

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CHD3 was upregulated in HCC. (A) The predicted target proteins

of FBW7 (Ubibrowser). (B) The differentially expressed CHD3 in LIHC (n =

374) and normal samples (n = 50) (starBase). (C,D) CHD3 mRNA (C) and

protein (D) expressions between HCC cell lines (HCCLM3 and HepG2) and normal cell

line (HL-7702) (quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction;

western blot,

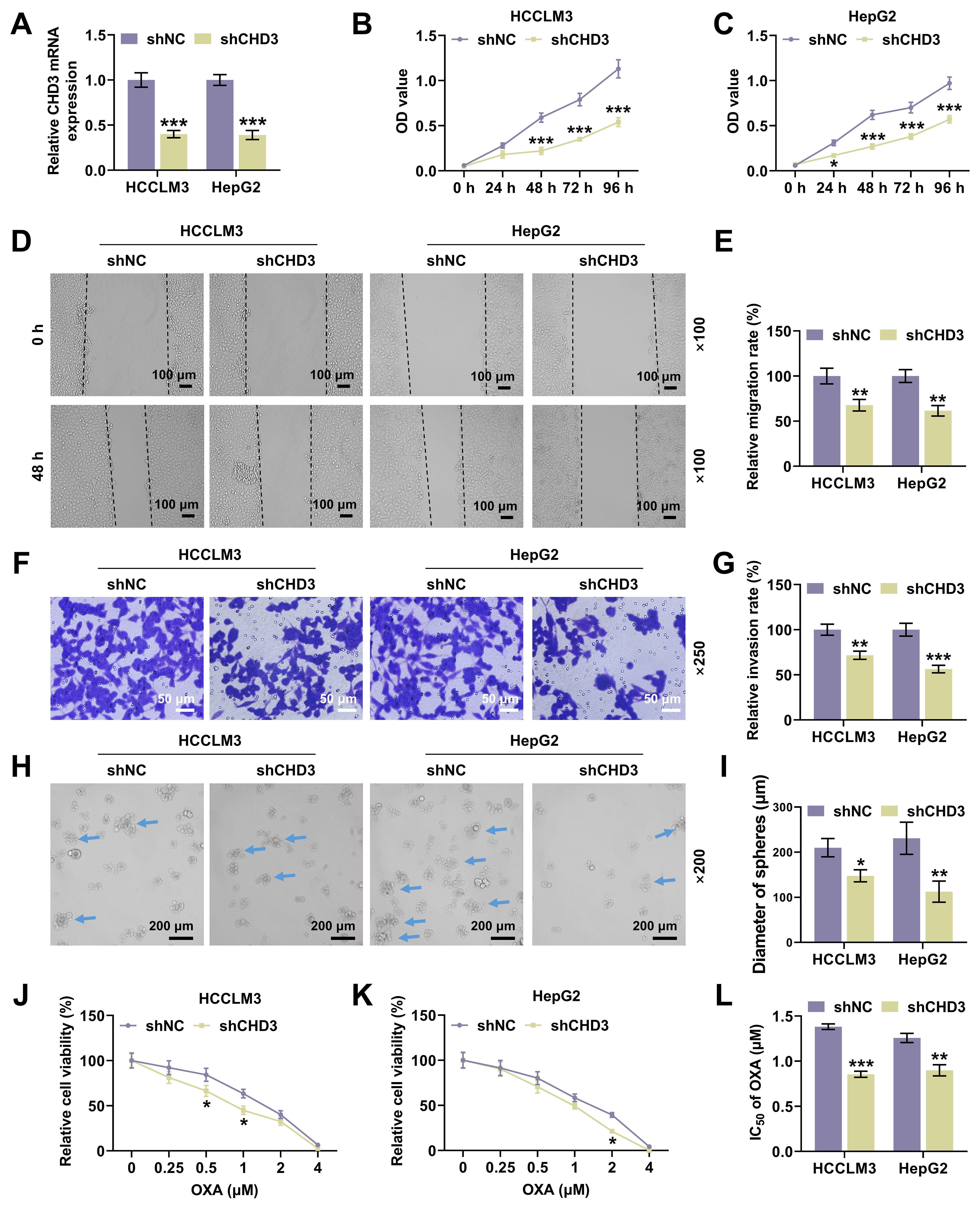

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

CHD3 knockdown attenuated HCC cell proliferation,

migration, invasion and stemness. (A) CHD3 mRNA expression of HCCLM3

and HepG2 cells after transfection of shCHD3 (qRT-PCR,

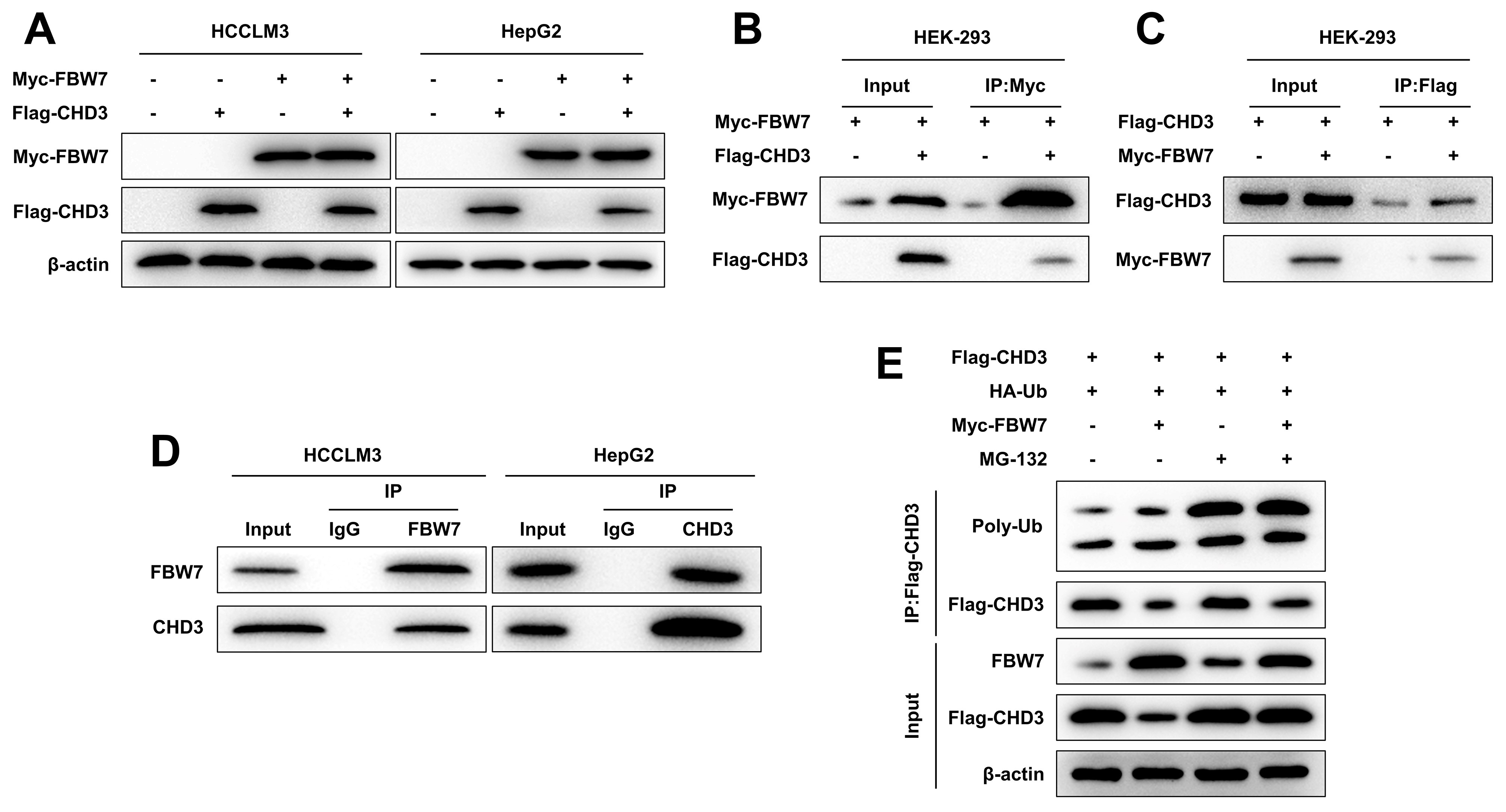

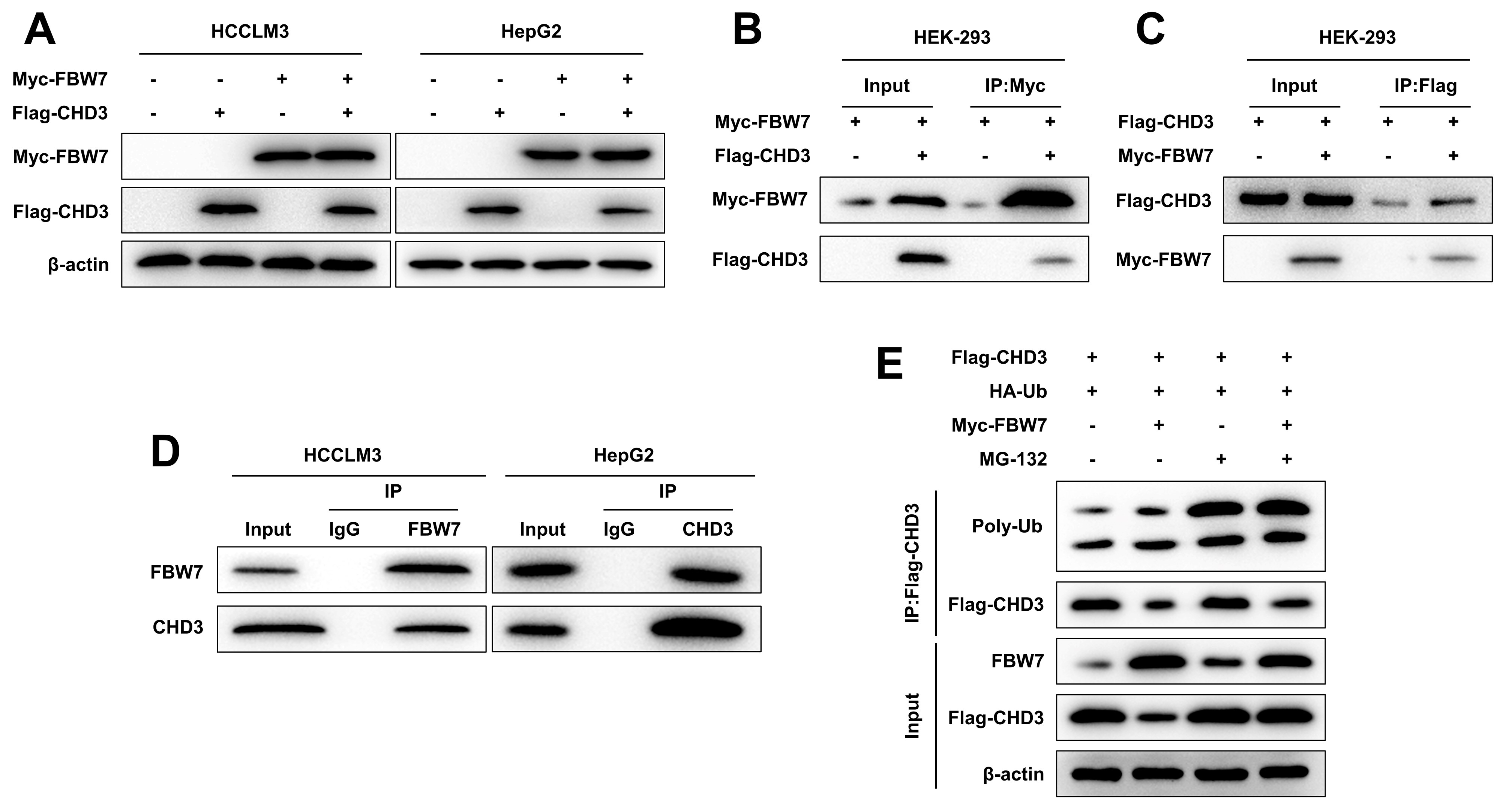

As per western blot data, the co-transfection of FBW7 and CHD3 overexpression plasmids decreased CHD3 protein level in HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells, while transfection of CHD3 overexpression plasmid alone barely impacted FBW7 protein expression (Fig. 3A), implicating that FBW7 overexpression declined the stability of CHD3. Then, we dug into the interaction of FBW7 with CHD3. Myc-FBW7 and Flag-CHD3 were co-transfected into HEK-293 cells. It was discovered that IP of Myc-FBW7 by anti-Myc antibody brought about Co-IP of Flag-CHD3, and Flag-CHD3 was co-immunoprecipitated with Myc-FBW7 by anti-Flag antibody (Fig. 3B,C). Additionally, IP analysis showed that endogenous FBW7 and CHD3 were immunoprecipitated from HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells, with endogenous FBW7 and CHD3 detected, respectively (Fig. 3D). These results mirrored FBW7 can interact with CHD3. Hence, to validate whether FBW7 modulates CHD3 stability via this activity, Flag-CHD3 and HA-Ub were co-expressed in HEK-293 cells with/without Myc-FBW7. Overexpression of FBW7 reduced CHD3 expression and may promote ubiquitination degradation of CHD3. Further, the effect of FBW7 overexpression were antagonized by MG-132 (Fig. 3E). This suggests that FBW7 promotes ubiquitination degradation of CHD3 through the MG-132 (Fig. 3E). These findings implied that FBW7 mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation to regulate CHD3 protein expression.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

FBW7 targeted CHD3 for ubiquitination. (A) Western blot of

exogenous FBW7 and CHD3 in HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells co-expressing FBW7 and CHD3

(

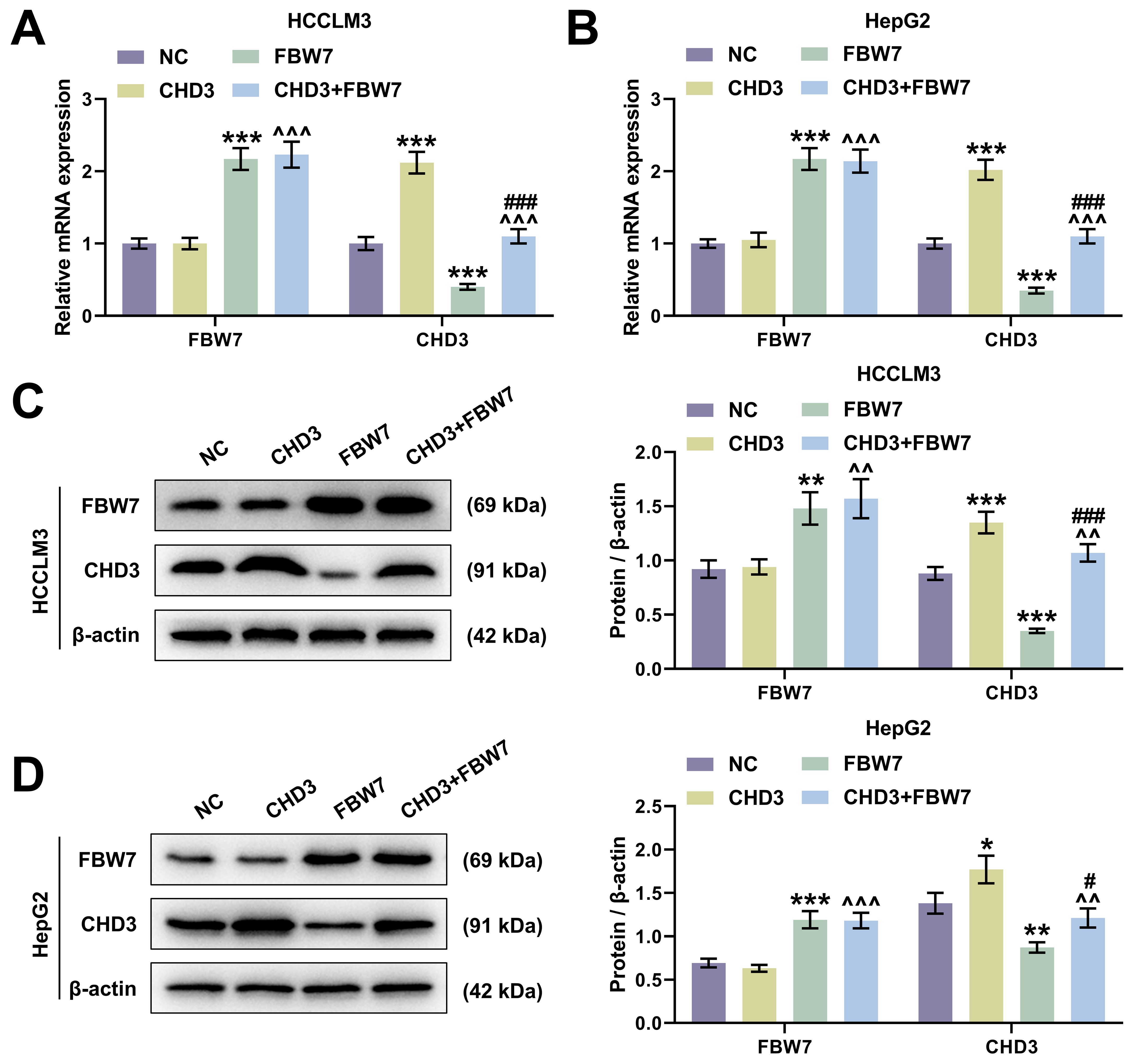

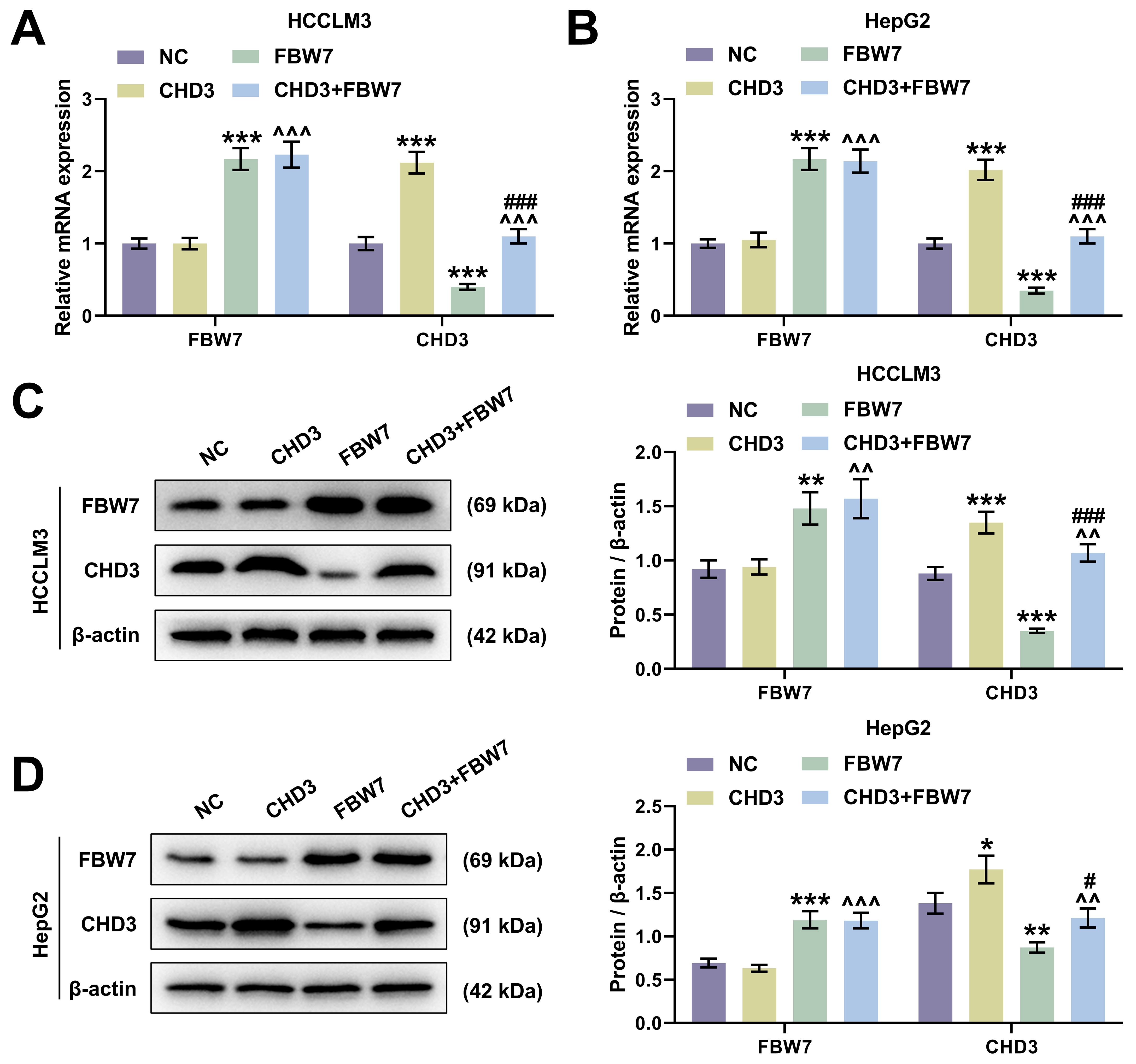

In HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells, FBW7 overexpression apparently raised FBW7

level and decreased CHD3 expression, whereas CHD3 overexpression notably

increased CHD3 level with FBW7 expression barely changed (Fig. 4, p

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

FBW7 overexpression targeted to repress CHD3 level in

HCC cells. (A,B) FBW7 and CHD3 mRNA expression of HCCLM3 (A)

and HepG2 (B) after transfection of FBW7 and CHD3

overexpression plasmids (qRT-PCR,

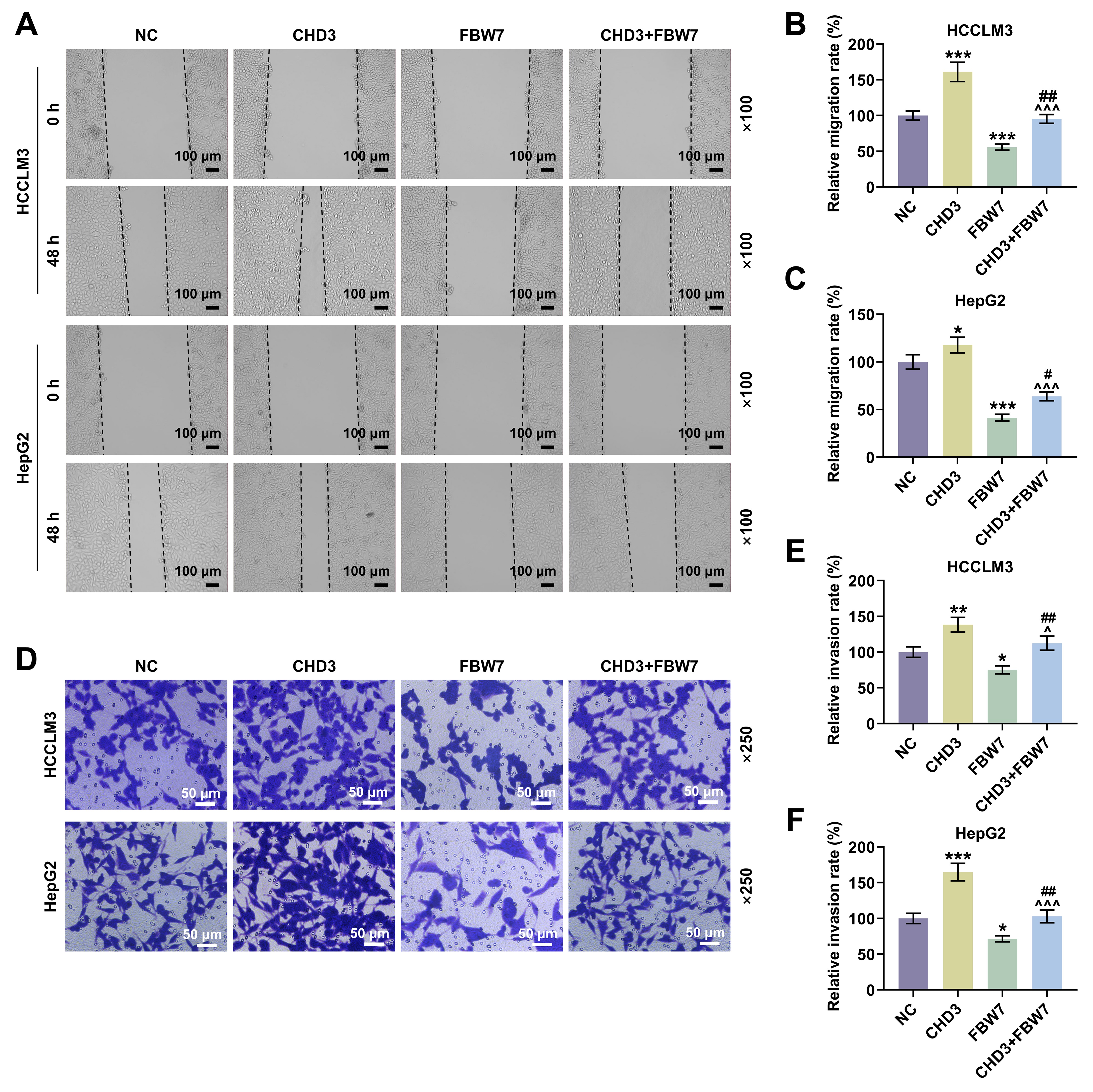

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

FBW7 overexpression mitigated the influences of

CHD3 on migration and invasion of HCC cells. (A) Representative images

of wound healing assay in HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells transfected with FBW7

and CHD3 overexpression plasmids (magnification:

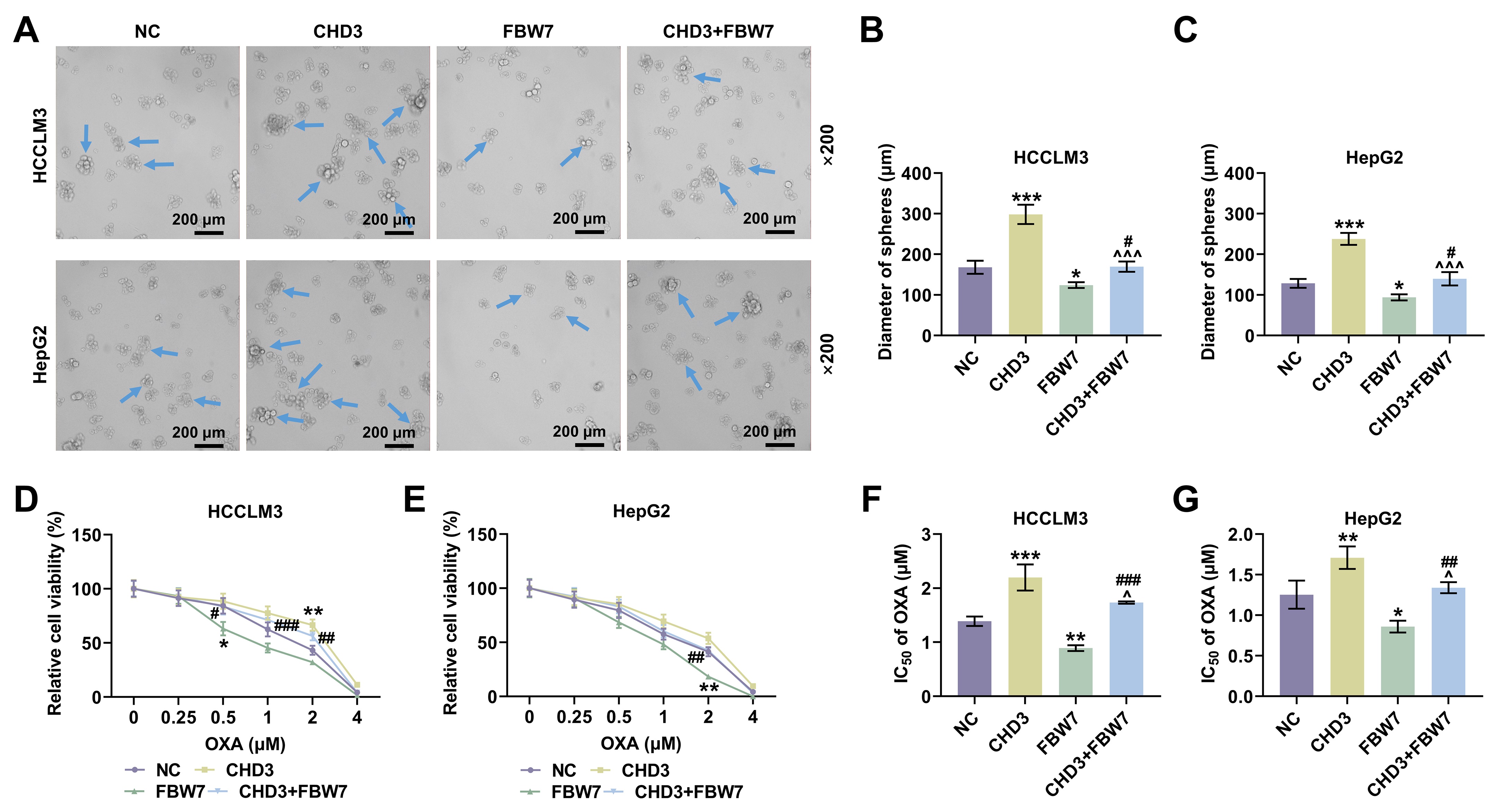

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

FBW7 overexpression mitigated the influences of

CHD3 on stemness of HCC cells. (A) Representative images of sphere

formation assay in HCCLM3 and HepG2 cells transfected with FBW7 and

CHD3 overexpression plasmids (magnification:

HCC is an increasingly severe public health problem globally, with tumor relapse and metastasis usually leading to a poor prognosis of patients [8, 21]. As a kind of E3 that participates in ubiquitination, FBW7 is considered to be a tumor suppressor in many human malignancies including HCC, and can also modulate stem cell behaviors [17, 22]. Nevertheless, no elucidation was provided on the influence of FBW7 on HCC up to now. To probe into the effect of FBW7, Ubibrowser was employed to predict the proteins targeted by FBW7 and CHD3 was obtained. Through the analysis of Genelikes Me, CHD3 and CHD4, which belong to the same family, have the highly similar function. It has been documented that CHD4 is upregulated in HCC and closely associated with cancer cell stemness [23]. Thus, we presumed that FBW7 might regulate CHD3 to participate in HCC.

To validate our hypothesis, we investigated the role of CHD3 in HCC firstly. Similar to the level of CHD4 in HCC [23], both of bioinformatics and qRT-PCR data exhibited marked upregulation of CHD3 in HCC cells, implicating a possible connection between CHD3 and HCC onset and progression. Moreover, we found through loss-of-function assays that CHD3 depletion dampened cell proliferation, migration and invasion. Capable of unlimited self-renewal, stem cells are a class of cells possessing extraordinary potential for differentiation into a full spectrum of cells [24]. With the development of stem cell research, cancer stem cells (CSCs), also named cancer stem-like cells or tumor-initiating cells, have won much attention in recent years, though their concepts are still controversial and their roles in tumor biology perhaps depend on the tumor type [25, 26, 27]. Having stem cell characteristics such as differentiation and self-renewal abilities, CSCs conduce to the generation and amplification of tumor cell population among a variety of cancers in brain, head and neck, prostate, lung, breast, colon and pancreas and haematopoietic tumors [28]. As for HCC, previous study has confirmed the significance of cell stemness as it reflects the tumor nature and intimately connects with a poor outcome after operation [29]. Besides, accumulating evidence has revealed that liver CSCs contribute to tumor occurrence and advancement, with HCC possibly conforming to the hypothesis of CSCs [30, 31, 32]. In our research, we observed CHD3 knockdown suppressed cell stemness in HCC, indicating CHD3 served as an oncogene in HCC.

Secondly, we explored how FBW7 acts on CHD3 in HCC. The ubiquitin-ligase FBW7 exerts critical effects on repressing tumor via multiple mechanisms, in which a fundamental one is targeting a number of proto-oncogenes for proteolysis. A former paper has determined that in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, FBW7 degrades STAT3 by ubiquitination to modulate cell proliferation and apoptosis [15]. Similarly, our study discovered that FBW7 decreased the stability of CHD3 in HCC cells and FBW7 interacted with CHD3, with further experiments verifying that FBW7 targeted CHD3 to mediate its ubiquitylation and degradation. Thus we inferred that FBW7 interacted with CHD3 for degradation through ubiquitylation in HCC.

Thirdly, in order to address whether FBW7 fulfills its functions on HCC via degrading CHD3, the HCC cell model co-expressing FBW7 and CHD3 was established. The protective function of FBW7 has been affirmed in numerous cancers, including HCC. For instance, overexpressed FBW7 has been proven to prominently decline the invasive capacity of HCC cells [14]. In the present research, the overexpression of FBW7 restrained cell migration, invasion and stemness in HCC, which again confirmed the role of FBW7 as a tumor suppressor. Furthermore, we validated that FBW7 overexpression abrogated CHD3-induced enhancement of migratory and invasive competences as well as stemness in HCC cells, implying that the suppressive effects of FBW7 on HCC were indeed realized at least partially by repressing CHD3. We found that FBW7 improved oxaliplatin sensitivity. Consistently, a previous study also showed that FBXW7 can improve chemotherapy resistance to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer (CRC) by directly binding to miR-128-3p [33]. Reconstitution of FBW7 function can restore cell sensitivity to drugs, suggesting that FBW7 loss, which is often observed in different human cancers, may be a cause of changes in drug resistance, and targeting p53 pathway and micro RNA (miRNA) can promote FBW7 expression [34]. Diminished FBW7 level leads to MCL-1 stabilization, and the combination of JQ1 with an MCL-1 inhibitor resensitized the FBW7 knockdown tumours to JQ1 treatment in vivo [35]. MCL-1 is predominantly involved in resistance in HCC cells [35]. This reminds us that the molecular mechanisms by which FBW7 mitigates cancer and promotes oxaliplatin sensitivity are complicated and diverse, resulting in the requirement of further investigations.

However, there is a limitation in this study. The quantification of CHD3 in HCC tissue is still lacking in this study. Also, there is a dearth of in vivo experiments to verify these results.

In conclusion, our study identifies CHD3 as an oncogene in HCC and further demonstrates that FBW7 overexpression suppresses HCC cell metastasis, stemness and oxaliplatin resistance via targeting CHD3 for epigenetic ubiquitylation and degradation, which might provide an innovative and promising method for HCC therapy.

The analyzed data sets generated during the study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Substantial contributions to conception and design: SL. Data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation: TF, CW. Drafting the article or critically revising it for important intellectual content: All authors. Final approval of the version to be published: All authors. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved: All authors.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.fbl2910357.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.