1 Department of Emergency Medicine, Zhejiang University Medical College Affiliated Jinhua Hospital, 321000 Jinhua, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

Epigenetics refers to heritable changes in gene expression and function that impact nuclear processes associated with chromatin, all without altering DNA sequences. These epigenetic patterns, being heritable traits, are vital biological mechanisms that intricately regulate gene expression and heredity. The application of chemical labeling and single-cell resolution mapping strategies has significantly facilitated large-scale epigenetic modifications in nucleic acids over recent years. Notably, epigenetic modifications can induce heritable phenotypic changes, regulate cell differentiation, influence cell-specific gene expression, parentally imprint genes, activate the X chromosome, and stabilize genome structure. Given their reversibility and susceptibility to environmental factors, epigenetic modifications have gained prominence in disease diagnosis, significantly impacting clinical medicine research. Recent studies have uncovered strong links between epigenetic modifications and the pathogenesis of metabolic cardiovascular diseases, including congenital heart disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. In this review, we provide an overview of the progress in epigenetic research within the context of cardiovascular diseases, encompassing their pathogenesis, prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Furthermore, we shed light on the potential prospects of nucleic acid epigenetic modifications as a promising avenue in clinical medicine and biomedical applications.

Keywords

- epigenetic modification

- cardiovascular disease

- DNA methylation

- histone modification

- RNA modification and non-coding RNAs

- gene regulation

- data integration

The cardiovascular system is a vital organ system in the human body, with its development influenced by various genetic mechanisms. Individual genes play a significant role in shaping the morphology and function of the cardiovascular system during development [1]. In addition, numerous cell-to-cell signaling interactions and regulation play a crucial role in determining the function and structure of the cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular diseases result from a complex interplay of genetic and environmental factors, including lifestyle choices, physical activity, and dietary habits. Cardiovascular diseases are a conglomeration of various conditions like congenital heart disease, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. Furthermore, several genetic disorders, both monogenic and polygenic, are associated with cardiovascular diseases [2].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of epigenetic modifications in regulating cardiovascular disease. Epigenetics is a regulatory mechanism that modulates gene function, expression, and activity without altering the underlying DNA sequence [3]. It is considered a crucial regulatory mechanism in how cells respond to changes in their environment. Epigenetic changes encompass a range of alterations that are distinct from those caused by altering the DNA sequence. These changes can involve histone modifications and chromatin remodeling through DNA methylation or hydroxymethylation etc. Moreover, recent research has also identified histone variants, microRNAs (miRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (LncRNAs) as additional epigenetic markers with relevance to cardiovascular diseases [4].

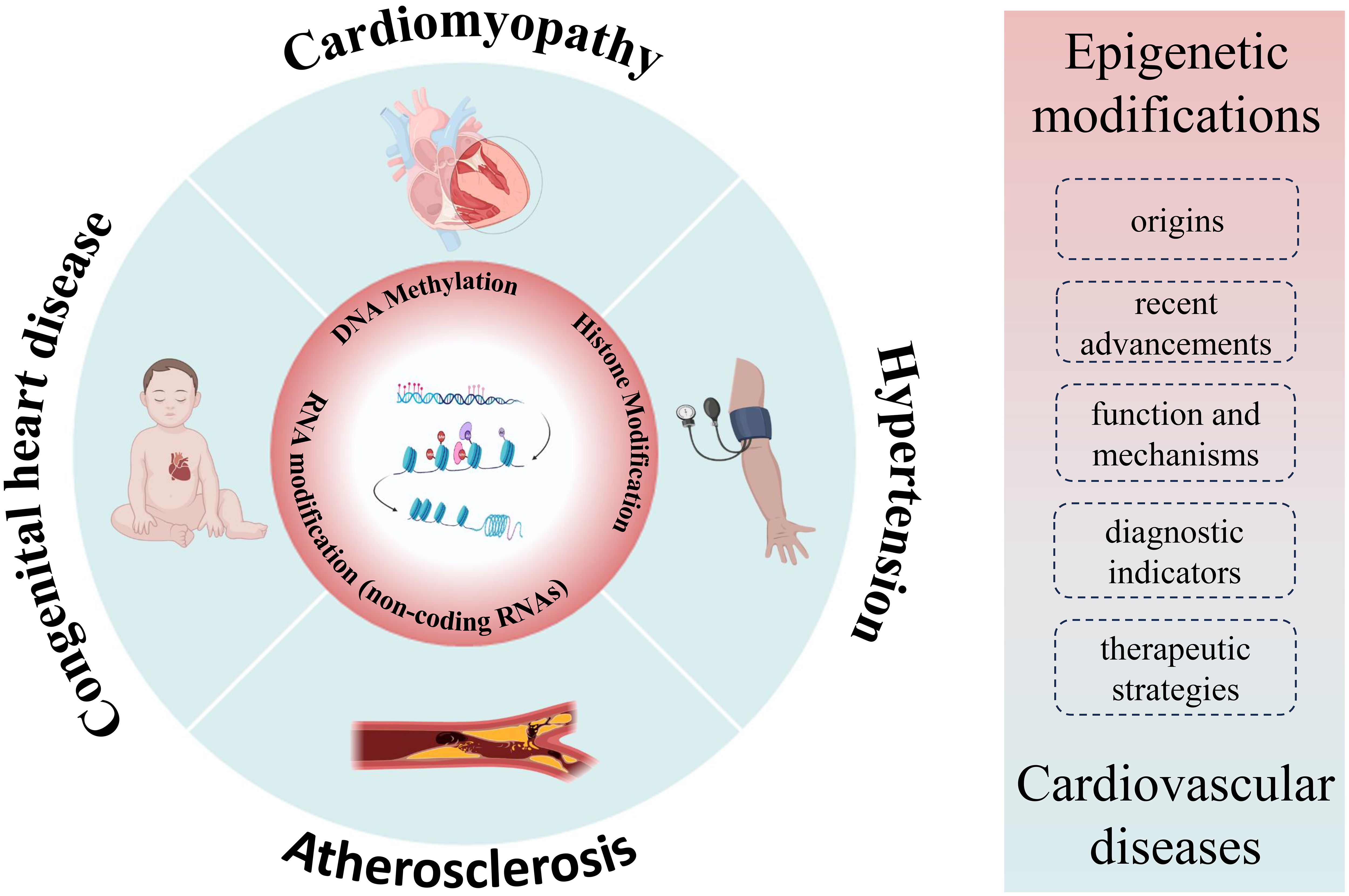

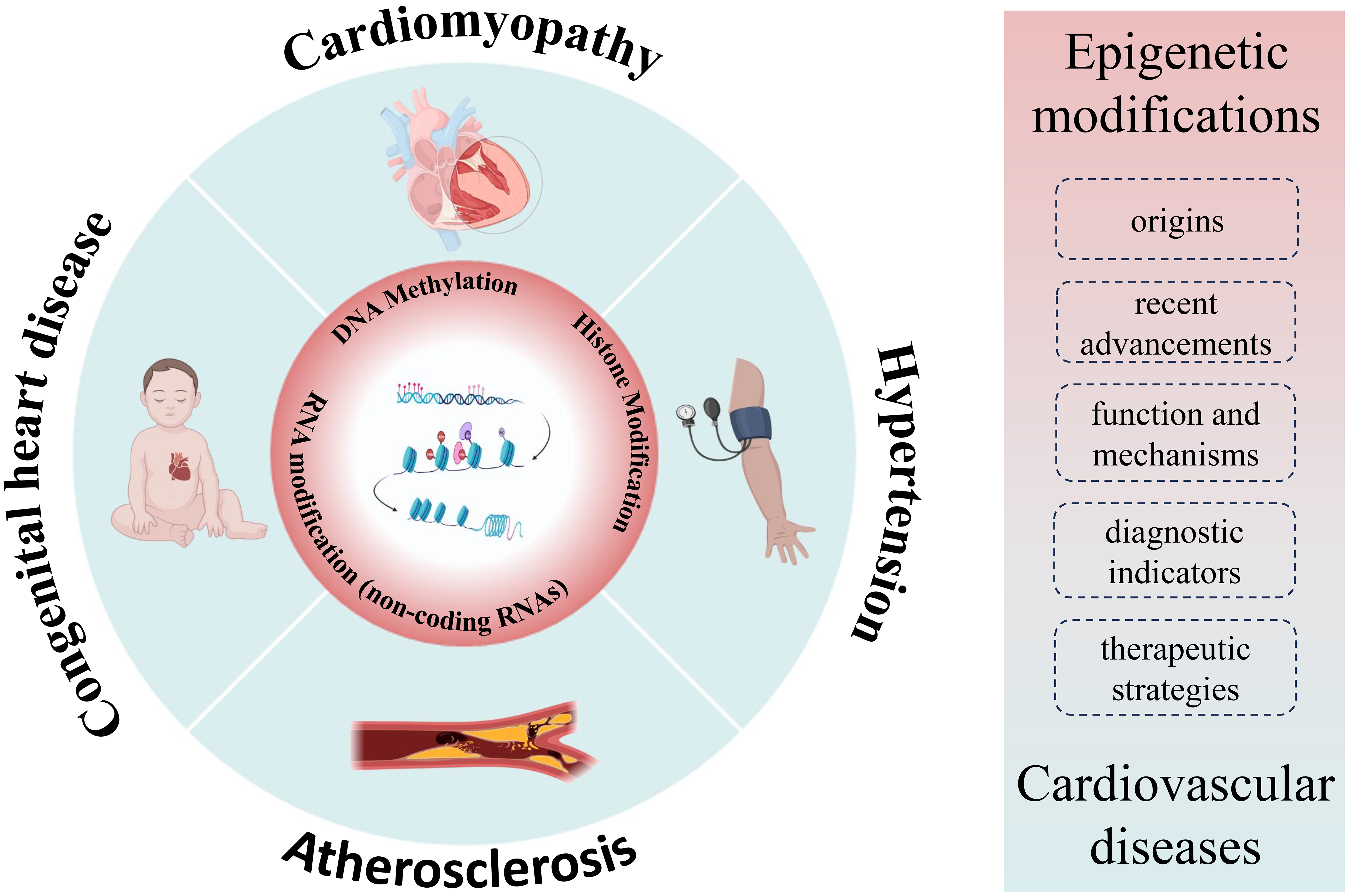

In this review, we aim to cover three main aspects: (1) the origins and recent advancements in our understanding of epigenetic modifications, (2) the function and mechanisms by which epigenetic modifications operate, and (3) the role of epigenetic modifications in cardiovascular diseases. It’s important to note that while significant progress has been made in elucidating the epigenetic aspects of cardiovascular diseases, a comprehensive understanding is still evolving. Further exploration of novel epigenetic regulatory mechanisms holds promise for more effective diagnostic indicators and potential therapeutic strategies for cardiovascular diseases (Fig. 1). This article critically examines the significance of epigenetics in investigating cardiovascular diseases, delving into its fundamental mechanisms, and highlighting the notable advancements in its application for the identification and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Overview of cardiovascular-epigenetic relationships. Summarizing the nexus between cardiovascular diseases and epigenetics, encompassing origins, advancements, function, mechanisms, and the role of epigenetics in cardiovascular diseases.

The term “epigenetics” originally coined by the renowned biologist Conrad Hal Waddington in 1942, signifies a groundbreaking concept in biology. It elucidates the heritable changes in gene expression and function that occur without alterations to the underlying DNA sequence. Now holding a central position in the rapidly advancing field of biological research, epigenetics encompasses DNA methylation, chromatin conformational modifications, and other mechanisms [5]. These processes maintain and transmit genetic information, influencing relevant traits in offspring.

Inheritance and variation are inextricably linked, with variation serving as the cornerstone of inheritance. Without variation, genetic material would remain static, rendering organisms ill-equipped to adapt to new or changing environments, ultimately leading to species extinction. At the molecular level, genetic variation arises from changes in the bases that make up the DNA sequence, which can include single base substitutions, deletions, and insertions, changes in the number of genes, or rearranging chromosome segments that contain multiple genes. According to the classical theory of genetics, genetic variation results from alterations in nucleotide sequences, culminating in changes in gene expression or function and ultimately manifesting as variations in characteristics [6]. However, classical genetics cannot account for certain genetic phenomena observed in life, such as the fact that every cell in the human body harbors the same set of genes yet differentiates into different types of cells and develops into different tissues and organs. Furthermore, even with identical genes, identical twins may not exhibit complete similarity in terms of appearance, speech, and behavior.

The solution to the conundrum lies in epigenetic variation, which fundamentally differs from genetic variation as it does not entail alterations in the DNA sequence, constituting the most pivotal characteristic feature of epigenetics. It suggests that the same genotype can lead to different phenotypes under varying environmental conditions [7]. The diverse range of developmental phenotypes exhibited by an individual is a clear manifestation of this concept. While an individual organism possesses only one genotype, it is crucial to recognize that phenotypes across different developmental stages, organs, and tissues vary significantly. Despite these phenotypic differences, all organs in our bodies share the same genotype. This is because genes are selectively expressed, and it is epigenetic variation that governs their regulation. Importantly, epigenetic variation does not necessitate alterations in the DNA sequence. In eukaryotes, DNA does not exist in isolation; it is intricately wrapped around histone molecules to form chromatin. Studies have shown that epigenetic variation arises from covalent chemical modifications of chromatin, which consists of DNA and histones [8]. More specifically, epigenetic variation encompasses alterations in DNA methylation, histone alterations, chromatin remodeling and changes in non-coding RNA abundance.

Epigenetic modifications have two main components: regulation during gene transcription and post-transcriptional regulation of genes. The former is employed for parental regulation, wherein environmental factors contribute to altered gene expression in offspring through mechanisms such as DNA methylation, covalent histone modification, chromatin remodeling, gene silencing, and RNA editing. The latter primarily investigates RNA regulatory mechanisms, including non-coding RNA (ncRNA), microRNA (miRNA), antisense RNA, riboswitches, and more. Somatic cells activate only a subset of all coding genes, and epigenetic modifications play a critical role in governing gene activity. These modifications ensure that genes needed in a particular cell are preserved and passed on to the next generation [9].

Epigenetic modifications, serving as key regulators of many vital processes and potential biomarkers of disease, constitute a powerful yet delicate regulatory mechanism within living organisms [10]. However, detecting and analyzing epigenetic modifications represent a significant challenge due to their intricate nature and dynamic behavior. The current techniques employed for epigenetic modification analysis suffer from various limitations, including multi-step procedures, time-intensive protocols, substantial sample consumption, and limited sensitivity. To address these shortcomings, recent advancements have led to the development of highly sensitive [11], high-throughput [12], dynamic, and efficient sensing analysis technologies, construct specific recognition probes through molecular cloning [13], supramolecular recognition [14], chemical derivatization [15], etc. Furthermore, they integrate high-performance nanomaterials, enzymes, or functionalized DNA to achieve signal amplification, thus constructing highly sensitive bio/chemical nano-sensing interfaces [16]. When coupled with DNA, these advancements have enabled the construction of DNA nanoarray platforms, facilitating high-throughput detection of epigenetic modifications in actual samples, such as cells and tissues. Additionally, these technologies have facilitated logical analyses, allowing us to examine the effects of external molecules, such as drugs, on epigenetic modifications and to explore the regulatory role of epigenetic modifications [17].

In the last few years, the scope of epigenetics research has expanded beyond the

realm of genetics. Epigenetic pathways are providing new insights into the

regulation of genes involved in human cardiovascular disease (CVD). For example,

tissues affected by atherosclerosis (AS) and peripheral blood cells from AS

patients exhibit aberrant genome methylation [18]. Altered methylation levels of

the 11

The application of epigenetic technologies holds promise in enhancing our understanding of various human diseases and discovering and identifying early warning and prevention targets for disease. Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common type of birth defect characterized by congenital malformations of the heart wall, valves, or blood vessels, and can be divided into several phenotypes, including atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. For instance, in the case of TOF, a congenital heart disease with four primary characteristics, including ventricular septal defect, aortic anomalies, pulmonary stenosis, and right ventricular hypertrophy [23]. The study demonstrated that the RXRA promoter region’s methylation status in the right ventricular outflow tract myocardium was significantly elevated in TOF patients. This methylation alteration was accompanied by a decrease in RXRA mRNA levels, providing insights into TOF’s pathogenesis and potential therapy targets [24]. Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DbCM) characterized by alterations in heart tissue function and structure in individuals with diabetes mellitus (DM), has been studied, revealing that histone modifications play a crucial role in cardiac remodeling in DbCM [25]. Non-specific inhibitor-based histone deacetylases (HDACs) demonstrated potential in enhancing cardiac function and reversing DM-induced cardiac remodeling in diabetic mice, indicating their candidacy as therapeutic agents for DbCM [26]. Hypertension, characterized by elevated blood pressure in systemic arteries, is a condition that has been explored in the context of epigenetics. For instance, Angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy, vascular remodeling, and hypertension can be attenuated by overexpression of the histone deacetylase SIRT1 in vitro [27, 28]. Atherosclerosis, characterized by the thickening of arterial walls, is the primary cause of coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular disease [29]. Studies have shown that the hematopoietic DNA demethylase TET2 plays a crucial role in preventing atherosclerosis by inhibiting the upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as well as the activation of inflammatory vesicles [30]. These findings suggest TET2 as a potential therapeutic target for atherosclerosis and other cardiovascular diseases.

With the advent of the Precision Medicine Initiative for the next century, there is a need for noninvasive biomarkers that can diagnose disease at the mechanistic level and novel or repurposed drugs that can precisely target these mechanisms to improve the current standard of treatment. The integration of clinical and genomic or even multi-omics datasets (e.g., transcriptomics and proteomics [31]) has revealed novel disease-specific molecular pathways in cardiovascular disease. Epigenetics includes regulatory mechanisms that do not affect DNA sequence but alter chromatin compaction to regulate gene expression. DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility regulation and histone tail modification are key regulators of important cellular processes such as differentiation, survival and response to external stimuli [32]. Individually or in combination, these mechanisms are often implicated in the pathogenesis of disease and offer opportunities for the improvement of disease diagnosis and the prediction of clinical outcomes [33]. Among the most well-characterized epigenetic modifications are DNA methylation and histone modifications. The latter category encompasses various modifications, including methylation, acetylation, ubiquitylation, and phosphorylation. These two fundamental processes, DNA methylation and histone modifications are intricately intertwined and collaborate in chromatin remodeling. Consequently, they contribute to the dynamic regulation of gene expression in higher eukaryotic cells. Furthermore, the recently discovered regulatory non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as pivotal players within the epigenetic landscape. They mediate post-transcriptional gene silencing and exert significant influence in pathological contexts, such as cancer, neurological disorders, and cardiovascular diseases, as well as non-pathological conditions. In the following section, we will delve into the detailed functions and mechanisms underlying epigenetic modifications, shedding light on their crucial roles in regulating gene expression and impacting diverse biological processes.

DNA methylation represents a precise mechanism for modifying genetic material without altering the DNA sequence itself. It involves a chemical modification of DNA that can influence gene expression while preserving the DNA sequence integrity. Methylation primarily occurs at CpG islands [34], and this process plays a pivotal role in regulating gene expression, maintaining epigenetic patterns, and is associated with various biological processes and diseases. A comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms governing DNA methylation is essential for advancing our knowledge of gene regulation and disease mechanisms.

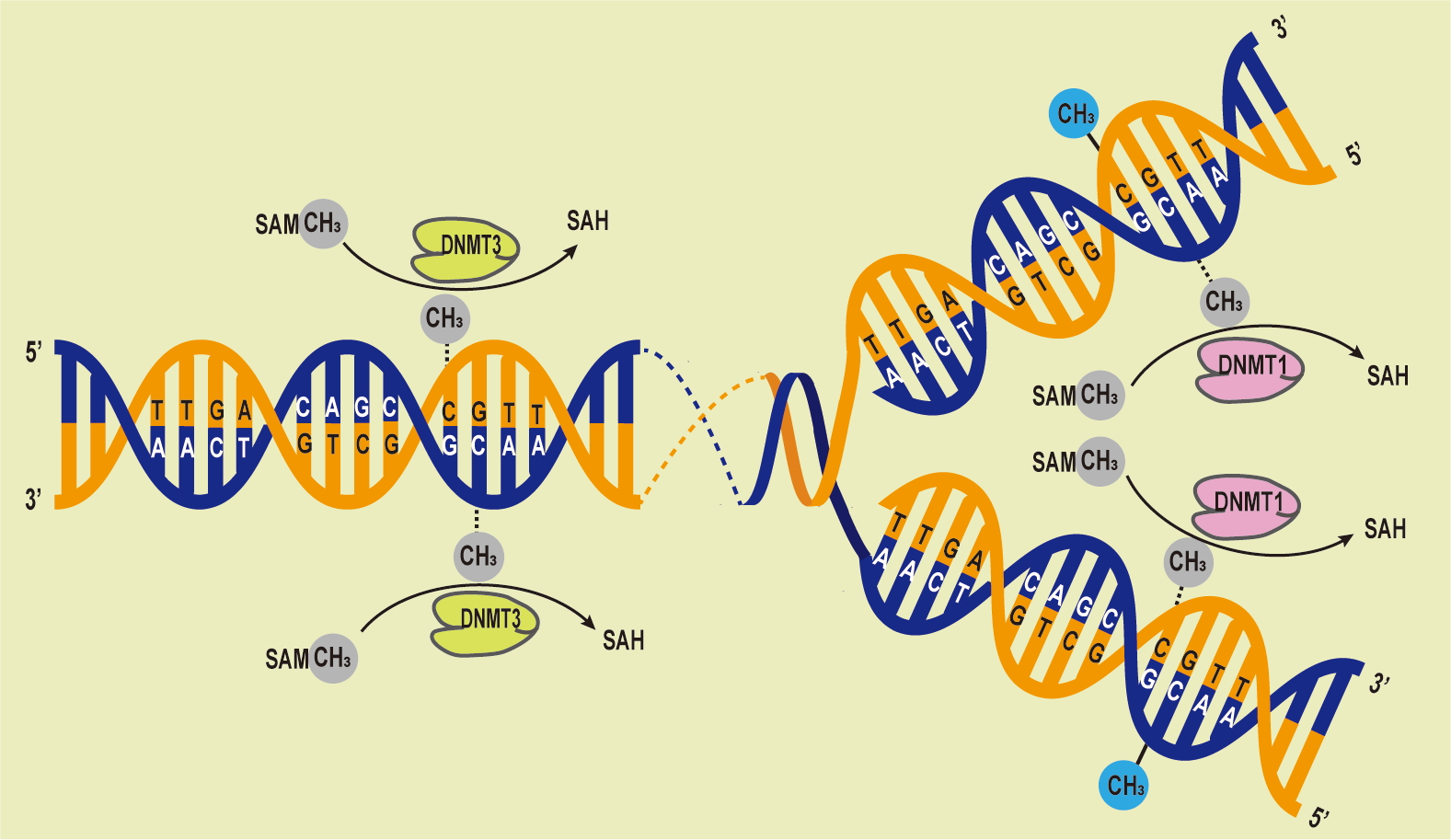

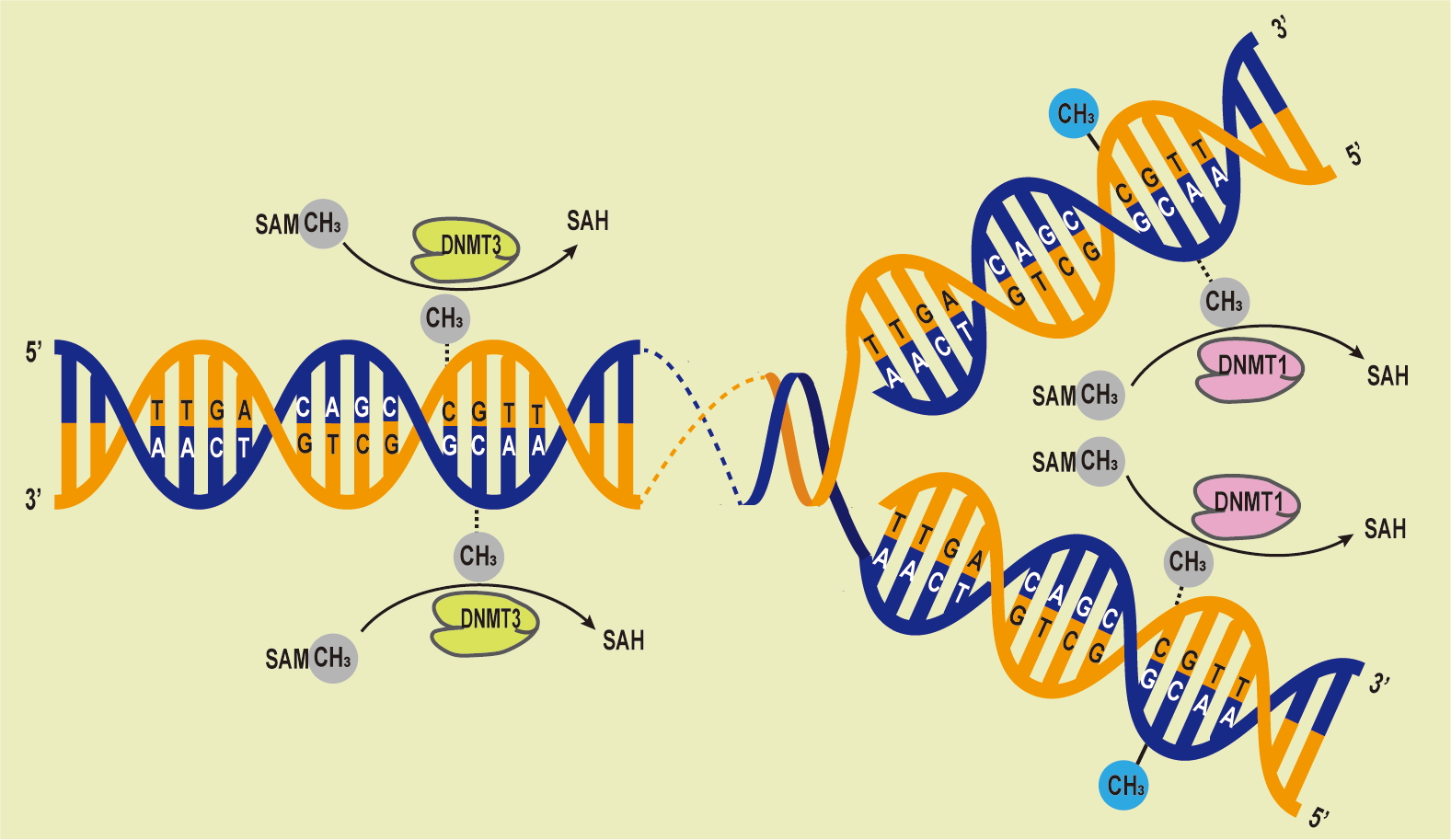

DNA methylation has a significant impact on cellular differentiation, physiological conditions, X chromosome deactivation [35], gene imprinting [36], and the repression of retrotransposons [37]. DNA methylases can be categorized into three groups based on their roles in DNA methylation: writers, erasers, and readers [38]. Because epigenetic modifications are partially reversible, chromatin-acting epimeric drugs are available for the treatment of complex human diseases. DNA methyltransferases (Dnmts) has rapidly gained significant clinical importance. Dnmts serve dual functions in both maintenance and de novo DNA methylation processes, and they are responsible for methylating DNA in the genome [39]. Specifically, Dnmt1, Dnmt3a, and Dnmt3b are essential for the regulation of gene expression. These enzymes possess distinct N-terminal regulatory and C-terminal catalytic domains, and their expression and functionality may vary. Dnmt1 is responsible for maintaining DNA methylation profiles following DNA replication and cell division, while Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b facilitate de novo DNA methylation at previously unmethylated loci [40]. Dnmt1 is the primary methyltransferase capable of methylating DNA in regions with low CpG content but maintaining DNA methylation in CpG-dense regions requires cooperation with Dnmt3a/3b [41, 42] (Fig. 2). In mouse embryonic stem cells, maintaining DNA methylation profiles for repetitive elements necessitates the presence of both Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a and/or Dnmt3b [43].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.DNA Methylation Processes Overview. The DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) family catalyzes the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenyl methionine (SAM) to cytosine residues, forming 5mC. Dnmt3 methylate unmethylated DNA, while Dnmt1 maintains methylation patterns during replication, preserving the original pattern during semiconservative replication.

DNA methylation is the process of attaching methyl groups to deoxyribonucleotides, altering the secondary structure of DNA and how it interacts with other proteins and noncoding RNAs. DNA methylation plays a crucial role in cardiovascular disease through two main mechanisms: regulating the expression of genes related to cardiovascular disease and interacting with environmental factors. For example, in patients with atherosclerosis, the promoter region of Trigger Act 2 (TEF2), which regulates the photosynthetic pigment gene, is significantly hypermethylated, while TEF2 mRNA levels are decreased. In addition, under a high-salt diet, the level of SDS- versus HDAC-mediated DNA methylation is increased, allowing suppression of gene expression and leading to diseases such as hypertension. Recent research has linked DNA methylation to the expression of candidate genes associated with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and hypertension [44]. Aberrations in the methylation patterns of these candidate genes could serve as markers for evaluating the progression of cardiovascular diseases [45]. For example, a study in a mouse model of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) analyzed DNA methylation and mRNA expression data from multiple time points and identified five genes—Ptpn6, Csf1r, Col6a1, Cyba, and Map3k14—that contribute to AMI through DNA methylation regulation [45]. DNA methylation of DNMT3a has been linked to maintaining internal homeostasis within cardiomyocytes, particularly in the context of heart failure [46]. Moreover, hypermethylation of specific genes, including HEY2, MSR1, MYOM3, COX17, and miRNA-24-1, has been detected in septal tissues of patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, ischemic cardiomyopathy, and dilated cardiomyopathy [47]. DNA methylation has also been shown to play a significant role in the development of hypertension, with studies identifying associations between DNA methylation patterns and circadian blood pressure performance [48, 49]. DNA methylation has been identified in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Hypermethylation of the bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2 (BMPR2) promoter is associated with BMPR2 downregulation and PAH progression. And switch-Independent 3a (SIN3a), a transcriptional regulator, in the epigenetic mechanisms underlying hypermethylation of BMPR2 in the pathogenesis of PAH [33]. Reduced methylation levels in the mitochondrial fusion 2 gene have been linked to vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and endothelial cell injury, contributing to hypertension [49]. Additionally, hypomethylation of the interferon-gamma gene has been associated with fibrotic changes in blood vessels, leading to elevated blood pressure [50]. These findings underscore the close relationship between DNA methylation and the incidence of cardiovascular diseases.

Histone modification encompasses a complex series of processes involving methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation, adenylation, ubiquitination, ADP-ribosylation, and other enzymatic alterations. Within the genome of mammals, histone modifications exhibit extensive diversity, making their manipulation within the chromatin environment a fundamental biological inquiry. At the core of chromatin architecture are the highly conserved histones (H3, H4, H2A, H2B, and H1), serving as foundational elements for packaging eukaryotic DNA into repetitive nucleosome units, ultimately forming higher-order chromatin structures [51]. Histones influence chromatin compaction and accessibility through these various modifications, with particular emphasis on the extensively studied changes occurring in the N-terminal “tails” of histones. These tails protrude from the nucleosome, being readily accessible at its surface, and play a pivotal role in regulating gene transcriptional activity [52].

Histone methylation is orchestrated by histone methyltransferases and primarily targets the N atom of lysine (Lys) and arginine (Arg) side chains [53]. Among the well-documented histone methylations are H3K4, H3K9, and H3K27, each exerting distinct regulatory influences. Lysine methylation, known for its stability in gene expression regulation, associates methylated residues at position 4 on H3 with gene activation, while those at positions 9 and 27 are linked to gene silencing [54]. In contrast, histone arginine methylation constitutes a more dynamic process, with arginine methylation deficiency at H3 and H4 associated with gene silencing, whereas its presence contributes to gene activation.

Histone acetylation, under the governance of histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases, predominantly targets the highly conserved lysine position at the N-terminus of H3 and H4, serving as a hallmark of active histones [55]. This acetylation process involves structural domain variations among histone acetyltransferases, requiring their assembly into multiprotein complexes for successful acetylation. The HDAC family can be categorized into four classes based on structural similarities and substrate specificity [56]. Class I HDACs, which include HDAC-1, HDAC-2, and HDAC-3, predominantly reside within the nucleus, exerting significant impacts on cell survival and proliferation. Class II HDACs participate in cell differentiation, possessing both nuclear localization and export signaling sequences, allowing their movement between the nucleus and cytoplasm [57]. Class III HDACs, dependent on nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, primarily regulate apoptosis in monocytes [58], while Class IV involves Zn-dependent histone deacetylase 2, contributing to various biological processes [59]. Acetylation can modulate gene transcription by affecting histone charge and interactions with associated proteins, essentially creating a histone code with diverse regulatory effects (Table 1).

| Mechanism | Transcriptional effect | |

| DNA base modifications | ||

| Methylation (CpG dinucleotides) | ||

| Hydroxymethylation (CpG dinucleotides) | ||

| Histone code | ||

| Histone H3 | ||

| Acetylation (K9, K14) | ||

| Methylation | ||

| K4/9 | ||

| Histone H4 | ||

| Acetylation (K5, K8, K12, K16) | ||

| Methylation (K20) | ||

| RNA-based mechanisms | ||

| Repressive noncoding RNAs: Xist, ANRIL | ||

| Activating noncoding RNAs: HOTTIP | ||

ANRIL, antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus; HOTTIP, HOXA distal transcript

antisense RNA; K, lysine; S, serine;

Histone modification plays a pivotal role in epigenetics, and irregularities in this process can lead to aberrant gene expression patterns, ultimately contributing to the development of cardiovascular diseases [60]. Investigations into histone modifications have unveiled their potential impact on various cardiovascular conditions, including atherosclerosis, heart failure, hypertension, and arrhythmias [61]. Atherosclerosis, characterized by endothelial dysfunction, smooth muscle cell migration and proliferation, extracellular matrix accumulation, and lipid deposition, results in arterial wall stiffness and luminal narrowing, leading to tissue ischemia and necrosis [62]. Studies have revealed a significant reduction in the expression of histone modification-related enzymes during atherosclerosis development. HDACs, particularly HDAC-3, have been implicated in maintaining vascular endothelial cell integrity, regulating smooth muscle cell proliferation, and contributing to atherosclerosis formation. Endothelial cells exhibit notably high levels of HDAC-3 expression [63], while HDAC-7 contributes to maintaining low levels of endothelial cell proliferation. Additionally, HDAC-9 has been found to stimulate aortic processes by regulating low-density lipoprotein endothelial cells, thereby impacting vascular cell growth and apoptosis. Histone modifications also play a crucial role in the abnormal proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells, key processes in atherosclerosis development. Reducing HDAC-1, HDAC-2, and HDAC-3 expression suppressed the growth of vascular smooth muscle cells. Inhibitors like Trichostatin A, targeting HDAC-12, initiated signaling pathways, ultimately promoting the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells. In heart failure, arising from genetic susceptibility and environmental factors, histone modifications are closely associated with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, apoptosis, and interstitial fibrosis [64]. HDAC inhibitors have emerged as crucial in managing myocardial fibrosis and cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting angiotensin II and removing the extracellular matrix, thereby regulating the extent of myocardial fibrosis.

RNA modification constitutes a crucial facet of post-transcriptional regulation, extending its influence to various RNA types, including messenger RNA (mRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), ribosomal RNA (rRNA), small non-coding RNA (siRNA), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA). Recent scientific endeavors have expanded beyond the confines of DNA sequence analysis to consider RNA modifications as influential factors in disease risk prediction and treatment. RNA modifications can substantially impact RNA stability, translocation, and translation, thereby playing pivotal roles in diverse human diseases and biological processes.

Studies have revealed the complex relationship between RNA modification and cardiovascular disease, highlighting its role in disease initiation and progression [65]. Additionally, studies on tRNA methylation suggest that it may contribute to the proliferation and metabolic adaptations in cardiac myocytes, making it a potential factor in the development and progression of cardiovascular disease [66]. RNA modification also holds promise in cardiovascular disease treatment. Notably, the m6A-modifying enzyme METTL3 has been implicated in promoting angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) translation and synthesis, with METTL3 inhibition demonstrating promise in attenuating cardiovascular disease in obese rats [67].

Non-coding RNA, a category encompassing RNA molecules that do not encode proteins but play pivotal regulatory roles in cellular function and disease development, has recently gained substantial recognition in cardiovascular disease pathogenesis. This diverse group of RNAs encompasses long-stranded RNA, short-stranded RNA (e.g., small molecule RNA), and more [68]. Long non-coding RNAs (LncRNAs) are a subset of RNA molecules that are longer than 200 nucleotides. They have been shown to exert significant regulatory influences in cardiovascular diseases. For example, the Tyrosine kinase 2 regulator 1 (Tyk2-ROG1) gene encodes an lncRNA that negatively regulates inflammation and associated pathways in cardiovascular disease [69]. Conversely, abnormal elevation of Xist lncRNA expression in cardiomyocytes has been implicated in activating apoptosis and inducing cardiac hypertrophy, culminating in heart failure [70]. Consequently, Xist holds potential as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease.

Short non-coding RNAs, characterized by their compact size, encompass miRNAs, siRNAs, and LncRNAs, among others. One prominent miRNA, miR-1, boasts multifaceted roles in cardiovascular diseases. Its expression levels directly impact heart function, with studies suggesting its potential to mitigate cardiomyopathy’s pathological effects by regulating cardiomyocyte transformation while inhibiting cell proliferation and growth [71]. MiRNA-223, on the other hand, contributes to cardiomyocyte proliferation and endothelial cell apoptosis, thereby influencing atrial fibrillation occurrence [72]. LncRNAs, being pivotal regulators of gene expression impacting processes like cell proliferation, apoptosis, and myocardial remodeling, assume significant roles in cardiovascular disease development [73].

In cardiovascular disease, various non-coding RNAs assume distinct functions, contributing to a complex regulatory network. Consequently, a thorough exploration of their molecular mechanisms and functional characteristics promises to unveil novel therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers, significantly bolstering the scientific foundation of cardiovascular disease prevention and treatment.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death worldwide, and more sensitive and scalable methods to detect early risk and presence of CVD are needed to better prevent and improve survival from cardiac events. Recent research has shown that artificial intelligence (AI)-based diagnostic methods combined with epigenetic (DNA methylation) effects can be translated into clinically applicable methods [74]. Numerous research studies have illustrated the significance of epigenetic modifications in the development of cardiovascular diseases (Table 2, Ref. [75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100]). Over the years, research has uncovered a strong association between epigenetic modifications and the expression of regulatory genes in numerous ailments including congenital heart disease, cardiomyopathy, hypertension and atherosclerosis. It’s worth noting that technical terminologies such as epigenetic modifications shall be defined when first used. The mechanism and development of cardiovascular diseases involve the abnormal epigenetic modification status of major regulatory genes. Such genes can be targeted to assess the progression of cardiovascular diseases.

| Diseases | Epigenetics type | Major regulator | Effect | References |

| Congenital heart disease | DNA methylation | APOA5, PCSK9 | Promote | [75, 76] |

| Histone modification | H3K4, H2BK120 | Promote | [77] | |

| Non-coding RNAs | SOX4, HAS2, NF1 | Inhibit | [78, 79] | |

| Cardiomyopathy | DNA methylation | SERCA2a | Promote | [80, 81] |

| Histone modification | cTnI, ssTnI, HDAC1/2 | Inhibit | [82, 83, 84] | |

| Non-coding RNAs | _ | _ | _ | |

| Hypertension | DNA methylation | 11 |

Promote | [85, 86, 87] |

| Histone modification | SIRT3, DRP1, SIRT6 | Inhibit/Promote | [88, 89, 90] | |

| Non-coding RNAs | ACE2, CLIC4, ARF6 | Promote | [91, 92] | |

| Atherosclerosis | DNA methylation | VB6, MTHFR, LOX-1 | Inhibit | [93, 94] |

| Histone modification | HDAC1/2/3 | Promote | [95, 96, 97, 98] | |

| Non-coding RNAs | APOA, CXCL12 | Promote | [99, 100] |

Congenital heart disease (CHD) arises from anomalies in the heart and large blood vessel formation during embryonic development, presenting a significant threat to infants and children. Advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms of heart development have identified key genes involved in transcriptional control, signaling, and morphogenesis, some of which are involved in the development of congenital heart defects [101]. However, genome sequencing alone cannot predict or cure CHD. In addition to genetics, epigenetics plays a crucial role in heart development, with mounting evidence suggesting its dysregulation in CHD pathogenesis.

The etiology of CHD is complex and multifactorial, with 80% of cases attributed to the interplay between genetic and environmental factors. Genetic factors include single gene disorders, chromosomal disorders, and double gene disorders. Holt-Oram syndrome and Mafonte syndrome are examples of single-gene defects that can cause CHD phenotypes [102]. Chromosomal defects, including Down syndrome and trisomy 18, are common contributors [103]. Two-gene defects primarily involve cardiovascular structural deformities [104]. Maternal environmental risk factors, such as gestational diabetes mellitus, dietary deficiencies, drug use, maternal age, smoking, obesity, febrile illnesses during pregnancy, alcohol consumption, and viral infections, have been linked to CHD development in the offspring [105, 106, 107].

Epigenetic modifications regulate gene expression by modifying local chromatin structure, thereby influencing interactions between chromatin and DNA-binding proteins. DNA methylation differences have been observed in the hearts of embryos between E11.5 and E14.5, with correlations to altered gene expression [108]. For instance, the down-regulation of Hyaluronan synthase 2 (Has2) at E14.5 was associated with enhancer methylation mediated by DNA methyltransferase 3b [109]. Methylation levels of APOA5 and PCSK9 were found to be elevated in neonates with aortic valve stenosis (AVS), potentially indicating risk factors for adult congenital heart disease [75, 76]. Patients with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) and congenital ventricular septal defects (VSD) exhibited hypermethylation in the promoter region of cytochrome C oxidative synthase protein (SCO2) [110]. In several diseases, including advanced colorectal cancer and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, studies have shown the prognostic and predictive value of LINE-1 methylation [111, 112]. Maternal hypermethylation of LINE-1 DNA has been discovered to be related to a heightened risk of non-syndromic coronary heart disease. Maternal risk factors are linked to atypical DNA methylation, which subsequently results in the development of coronary heart disease [113]. Methyl for DNA methylation in cells is provided by folic acid, a B vitamin. Abnormal maternal folate metabolism puts the foetus at risk of coronary heart disease if folate deficiency results in hyperhomocysteinemia. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) is an important enzyme in folate metabolism [114]. MTHFR C677T mutation is associated with up to 50% of certain coronary heart diseases [115]. Recent studies have used Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis, Gene Ontology (GO) analysis and KEGG pathway analysis to identify 9625 differentially methylated genes associated with key cardiac developmental pathways. Among these, GO analysis revealed a strong association between prenatal placental DNA methylation and congenital heart disease (CHD), with certain genes such as TLL1, CRABP1, FDFT1 and PCK2 located within the differentially methylated regions being associated with clinical phenotypes [110].

Histone modifications have also emerged as potent regulators of chromatin structure and transcriptional control during heart development. It can affect the structure of chromatin and subsequently regulate the availability of transcription factors and initiation complexes, leading to the activation or silencing of genes [76]. Knockout experiments have highlighted the critical roles of various histone-modifying enzymes in heart development [116]. The naming conventions for histone modifications are contingent on the particular histone type, the amino acid type and location, and the modulatory type [117]. Histone modifications are primarily influenced by writing factors, such as methyltransferases and acetyltransferases, erasing factors, like demethylases and deacetylases, and reading factors, such as effector proteins that identify specific banding sites. Aberrant changes in these factors are closely linked to the development of coronary heart disease. It is essential to note that technical terms be explained when initially used. The study identified significant de novo mutations in genes responsible for the writing, erasing, and reading of H3K4 methylation during H3K4 methylation or H2BK120 ubiquitination. These findings suggest a potential pathogenic role of abnormal histone methylation in coronary heart disease [77]. WDR5 is a fundamental component of the human lysine methyltransferase (MLL) and SET1 histone H3K4 methyltransferase complex, encompassing SET structural domains. This complex is recognised as an interpreter of H3K4 methylation [118]. Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS), characterized by growth failure and organ dysfunction, is linked to the deletion of WHSC1, a candidate protein [119].

Non-coding RNAs, including long non-coding RNAs (LncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs), play pivotal roles in gene expression regulation. While miRNAs primarily interact with mRNA to repress translation, LncRNAs can directly engage with chromatin remodeling complexes to regulate transcription. Several studies have identified irregular miRNA expression in TOF patients, with miR-421 being implicated in SOX4 regulation [78]. Overexpression of miR-424 was associated with increased proliferation and decreased expression of HAS2 and NF1 in right ventricular cardiomyocytes from TOF patients [79]. Additionally, miRNAs hold promise for preserving and correcting cardiac function in structural heart disease patients, as they are critical for cardiomyocyte proliferation, maturation, and pathological remodeling [120].

Recent advances have focused on utilizing epigenetic biomarkers for the diagnosis of CHD [23]. Aberrant DNA methylation patterns and circulating miRNAs are being investigated as potential diagnostic indicators. In tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) cases, a genome-wide methylation assay identified 25 genes with high predictive accuracy for TOF, including those associated with heart development [121]. A similar approach in isolated ventricular septal defect (VSD) cases revealed 80 CpG sites in 80 genes highly accurate in predicting VSD [122]. Circulating miRNAs, such as hsa-let-7a and hsa-let-7b, demonstrate diagnostic value for atrial septal defects [123], and a panel of maternal serum miRNAs, including miR-19b, miR-22, miR-29c, and miR-375, shows promise for early fetal CHD diagnosis [124]. Despite these promising findings, the identification of specific and reliable biomarkers has not been confirmed. Further research is essential to establish the clinical utility of these epigenetic biomarkers in CHD diagnosis.

Cardiomyopathies constitute a group of myocardial diseases characterized by abnormal ventricular hypertrophy or dilation, with complex and varied etiologies. Although the genetic basis of all cardiomyopathies is a given, the intricacy of the genetic factors increases the difficulty involved in treating the ailment. Recent research has unveiled that cardiomyopathy phenotypes are influenced not only by genetic variations within the DNA coding sequence but also by the functional state of the genome itself [125]. Consequently, epigenetic studies have focused on elucidating changes in gene expression resulting from regulatory mechanisms.

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) represents one of the most severe complications of

diabetes. DCM is a multifactorial and heterogeneous condition marked by the

dilation of the left ventricle and impaired myocardial function. Due to

genome-wide variations in gene expression, epigenetic alterations help to

understand the pathogenesis of cardiomyopathies. Dynamic changes in DNA

methylation during cardiac development and disease are critical for cellular

differentiation. Studies have revealed that DNA methylation is associated with

cardiomyopathy [126]. For example, research by Movassagh and colleagues provided

a genome-wide DNA methylation profile of end-stage hearts in normal subjects

compared to patients with cardiomyopathy. They also demonstrated the association

between DNA methylation and cardiomyopathy [127]. Importantly, calcium

(Ca

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) is defined as a cardiomyopathy characterised by ventricular restrictive diastolic dysfunction with normal or reduced ventricular end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes and excludes ischaemic cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, pericardial disease and congenital heart disease. RCM is caused by a mutated cTnI gene. A cTnI mutation has been reported [128] and validated in animal models of restrictive cardiomyopathy in a cTnI mutant family [82]. RCM has a serious impact on the life and health of children. Epigenetic modifications mediated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) play a major role in heart development and disease. However, the role of epigenetic modifications in the diastolic dysfunction is not well understood. Studies have indicated that cTnI mice with cardiac-specific knockout exhibit acute diastolic dysfunction about 17–18 days after birth [84]. Epigenetic mechanisms, specifically changes in histone acetylation, have been implicated in the expression of cTnI and ssTnI in previous studies [82, 83]. DNA methylation has a negative impact on the expression of these genes. A gradual decrease in histone H3 acetylation in the SURE region upstream of ssTnI was observed in addition to the changes in DNA methylation levels [83]. This is an indication of the involvement of histone H3 acetylation levels in the regulation of ssTnI expression silencing. The histone H3 acetylation level in the key region of the cTnI promoter displayed identical tendencies, indicating its involvement in the regulatory mechanism of cTnI expression reduction [84]. Therefore, it is uncertain whether manipulating the H3 acetylation levels in the promoter regions of ssTnI and cTnI can be used to regulate their expression. It is also unclear if raised cTnI expression and restarting of ssTnI can improve diastolic dysfunction.

Studies have shown a significant correlation between histone modifications and the onset of DCM. For example, levels of histone H3 lysine trimethylation at positions IV and H3 lysine dimethylation at position IX generally exhibit decreases in DCM cardiac tissue compared to normal hearts [129]. In eukaryotes, there are four classes of acetylase genes (HDAC) identified. Cardiac-specific knockout of HDAC1 and HDAC2 leads to neonatal lethality and upregulation of DCM-related genes, including those encoding skeletal muscle-specific contractile proteins and calcium pathways [130]. However, the precise role of histone acetylation in the development of DCM remains incompletely understood.

Although the mechanisms that regulate blood pressure have been studied for many years in humans and in animal models, it has not been possible to identify the relevant genes and variants by linking single genes or genetic polymorphisms to hypertension [131]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) conducted in Europe and the United States have reported associations between more than 10 gene loci and blood pressure, but there are still many more genetic variants to discover [132]. A report by the NHLBI on epigenetics and hypertension, published in Hypertension in 2012, aimed to address three key questions: (1) Do epigenetic changes in humans influence blood pressure? (2) What are the epigenetic and environmental factors that contribute to initiating and developing hypertension, and what are potential diagnostic markers? (3) Is there a hereditary link between hypertension and epigenetic changes, which can accumulate across generations, or is it possible to reverse the link?

Epigenetic changes in hypertension are described with these three questions in mind. It is well known that the DNA sequence of a gene is only a template and that each cell of a higher organism must switch on or off its instructional genetic information by epigenetic modifications of the entire genome so that the entire set of genes expresses a diversity of cells and tissues. As well as regulating gene expression and inheritance, epigenetic modifications play a major role in the prevention and treatment of a wide range of chronic diseases, and these regulations are both accessible and heritable [133]. However, GWAS has also identified some hypertension genetic susceptibility loci that have little effect on population blood pressure, a phenomenon known as genetic deletion [134].

Epigenetics provides an interrelationship between the environment and nuclear DNA. Through the processes of glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), cellular mitochondrial metabolism produces energy [135]. Bioenergetic genes require cis- and trans-regulation of mitochondrial DNA and are present in both chromatin and mitochondrial DNA [136]. When the bioenergetic system converts thermal energy from the environment into an abundance of ATP, there is an increase in chromatin phosphorylation and acetylation levels, along with replication and transcription of mitochondrial DNA. Conversely, when energy conversion is limited, phosphorylation and acetylation are lost, resulting in the inhibition of gene expression [137]. Phosphorylation and acetylation play a crucial role in regulating cell signaling. This interaction between the environment and epigenetics ultimately contributes to the clinical phenotype of epigenetically regulated disorders.

Over the past decade, considerable evidence has shown that epigenetic

mechanisms, such as DNA or histone modifications, play an important role in the

regulation of gene expression in several diseases [138]. DNA methylation can

induce structural changes in chromatin by recruiting methyl CpG-binding protein

(MeCP) and HDAC [139]. MeCP2 has been shown to interact with DNA

methyltransferase (DNMT). Aberrant expression of DNMT and MeCP2 can affect DNA

methylation levels, leading to disease phenotypes [140, 141]. However, the

development and onset of hypertension are significantly associated with DNA

methylation. Methylation and demethylation of genes, such as 11

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) has become an important tool for regulating gene expression. RNA interference (RNAi) involves the use of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) to degrade or prevent the translation of a target gene mRNA, ultimately leading to the specific silencing of target gene expression. SiRNA-targeted silencing of p22phox (sip22phox) has been reported to inhibit the contractile response of smooth muscle cells induced by the NADPH oxidase Ang II [144]. RNA silencing also attenuates Ang II-induced levels of oxidative phosphorylation and its progressive enhancing response [145]. This research in the emerging field of genetic-environmental interactions has successfully advanced our understanding of epigenetic regulation in hypertension and vascular remodeling. The role of epigenetics in the development of hypertension and its potential reversibility to a certain extent provide a new target for hypertension prevention and treatment, laying the groundwork for personalized drug therapy.

However, it is worth considering whether epigenetic markers and traits cause or result from hypertension. Do epigenetic modifications play a role in the pathogenesis of hypertension-associated complications? What is the molecular basis of the epigenetic memory associated with transgenerational and intergenerational hypertension? Are epigenetic traits reliable markers for predicting or diagnosing hypertension in humans? How are these markers identified? In this regard, the combination of epigenetic studies with multispecies comparisons can yield evolutionary insights and perspectives that are beneficial.

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by the deposition of lipids, ultimately leading to acute cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarctions and strokes [146]. Atherosclerotic plaque development and rupture are the primary culprits behind these major cardiovascular events. A better understanding of epigenetic modifications holds the potential to further elucidate the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, as epigenetic changes may serve as a bridge between environmental and genetic factors [147].

Epigenetic modifications play a crucial role in regulating gene expression and altering protein and cell function in response to external stimuli. Recent studies have highlighted the causal link between stress and AS, determined by epigenetic patterns of gene expression regulation [148]. Risk factors for AS include epigenetic mutations in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and macrophages. Therefore, a comprehensive study of the epigenetic regulatory mechanisms of AS may yield new therapeutic strategies and molecular targets for the prevention and treatment of this condition.

DNA methylation is involved in various biological processes, including the regulation of gene expression, imprinting, embryogenesis, cell differentiation, and development in higher organisms. Studies have confirmed that genome-wide DNA methylation aberrations are closely associated with the development of AS. It was proposed in the late 1990s that abnormal DNA methylation patterns promote AS and that deficiencies in folate, vitamin B6, and B12 (which are necessary for methylation) lead to DNA hypomethylation, contributing to AS development [93]. Early in atherosclerosis development, the arterial wall exhibits genome-wide hypomethylation and hypermethylation of specific gene promoters [149]. Hypomethylation is known to promote the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells [150]. Studies have shown that mice with a genetic deletion of methylenetetrahydrofolate (MTHFR-/-) reductase and hyperhomocysteinemia exhibit aortic lipid deposition [94]. Prolonged exposure of human umbilical vein endothelial cells to oxidized low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) has been found to lead to increased DNA methylation mediated by haemagglutinin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1), enhancing anti-apoptotic effects in their offspring [57]. Therefore, an in-depth study of DNA methylation and its biological significance in the development of AS will provide a more accurate understanding of the influence of DNA methylation on the occurrence and progression of AS.

Histones undergo various covalent modifications, including acetylation,

methylation, ubiquitination, phosphorylation, glycosylation, and carbonylation,

which collectively constitute the histone code. Current research in histone

modification has primarily focused on histone acetylation. As a pathological

process characterized by chronic inflammation, nuclear factor-kappa B

(NF-

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are significantly expressed in the cardiovascular system and

are closely linked to cardiovascular diseases. Several miRNAs that are

exclusively expressed in endothelial cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells

have been discovered to participate in the pathogenesis of AS. For instance,

miR-33 overexpression in macrophages has been shown to reduce cholesterol efflux

to ApoA1, while upregulation of ABCA1 protein expression increases

cholesterol efflux to ApoA1 [153]. In murine models, ApoE

Building upon the historical context of epigenetics and inheritance mechanisms, this review offers a comprehensive exploration of epigenetic mechanisms in various cardiovascular diseases, encompassing DNA methylation, histone modification, and non-coding RNAs. It also provides a detailed summary of preclinical experiments related to epigenetic regulation and drug targets in cardiovascular diseases. In recent years, epigenetics has gained increasing prominence in the treatment of neovascular diseases. While DNA methylation and histone acetylation have been extensively studied in prevalent heart conditions, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, and atherosclerosis, our understanding of their roles in cardiovascular diseases is only beginning to unfold. Notably, the role of histone methylation in this context remains largely uncharted, presenting a promising avenue for future exploration.

Furthermore, substantial research efforts have been dedicated to investigating the potential of epigenetic drugs in managing cardiovascular diseases. For example, HDAC inhibitors have demonstrated promise in addressing atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. This discovery underscores the rationale for further developing HDAC inhibitors as a viable treatment modality for cardiovascular diseases. Presently, most of the research is centered on animal studies, and clinical trials to validate epigenetic inheritance are yet to be conducted. Clinical trials related to DNA methylation and histone acetylation have progressed through phases 1 to 3 for patients with coronary heart disease, myocardial infarction, and hypertension. However, the development of therapeutic targets for protein methylation and small molecule drugs targeting non-coding RNAs is still in its infancy, primarily due to the scarcity of large-scale fundamental clinical studies.

In summary, epigenetics holds significant promise in the diagnosis and management of cardiovascular diseases, potentially paving the way for precision medicine. Its influence on gene expression and disease development opens new avenues for research and clinical practice. Beyond enhancing our understanding of disease processes, epigenetics may play a pivotal role in advancing innovative treatments and diagnostic approaches. The goal is to develop highly specific epigenetic drugs with minimal side effects and reduced drug resistance, thereby improving the treatment of various cardiovascular diseases in the future. Ongoing research and development in the field of epigenetic therapies for cardiovascular diseases are poised to expand their applications, benefiting a broader spectrum of patients with cardiovascular conditions in the future.

XW and LK initiated and conceptualized the manuscript. XW, XT and CL performed the research, interpreted data and wrote the manuscript. XW and LK edited and reviewed the manuscript. LK supervised. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was funded by the Health Science & Technology Plan of Zhejiang Province (No. 2022ZH063).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.