1 Shandong Academy of Occupational Health and Occupational Medicine, Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, 250062 Jinan, Shandong, China

2 Public Health Monitoring and Evaluation Institute of Shandong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 250000 Jinan, Shandong, China

3 Department of Neurology, Affiliated Hospital of Qinghai University, 810000 Xining, Qinghai, China

4 Department of Respiratory Medicine, Children's Hospital Affiliated to Shandong University, 250022 Jinan, Shandong, China

Abstract

Neurodegenerative disorders are typified by the progressive degeneration and subsequent apoptosis of neuronal cells. They encompass a spectrum of conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Huntington’s disease (HD), epilepsy, brian ischemia, brian injury, and neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA). Despite the considerable heterogeneity in their clinical presentation, pathophysiological underpinning and disease trajectory, a universal feature of these disorders is the functional deterioration of the nervous system concomitant with neuronal apoptosis. Ferroptosis is an iron (Fe)-dependent form of programmed cell death that has been implicated in the pathogenesis of these conditions. It is intricately associated with intracellular Fe metabolism and lipid homeostasis. The accumulation of Fe is observed in a variety of neurodegenerative diseases and has been linked to their etiology and progression, although its precise role in these pathologies has yet to be elucidated. This review aims to elucidate the characteristics and regulatory mechanisms of ferroptosis, its association with neurodegenerative diseases, and recent advances in ferroptosis-targeted therapeutic strategies. Ferroptosis may therefore be a critical area for future research into neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords

- neurodegenerative diseases

- ferroptosis

- iron metabolism

- inhibition mechanism

- treatment

Neurodegenerative disorders pose a significant medical and public health burden worldwide. The incidence and prevalence of these disorders increases dramatically with age. As life expectancy continues to increase globally, the number of cases is therefore projected to rise. Neurodegenerative disease is characterized by the loss of neurons or their myelin sheaths, with progressive deterioration of the condition over time [1]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is primarily observed in individuals aged over 65 years and is characterized by the gradual deterioration of memory, language, and cognitive functions [2]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) also increases with age and is slightly more prevalent in males. PD is characterized by static tremors, bradykinesia, increased muscle tone, and postural instability. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is typified by progressive skeletal muscle weakness, muscle atrophy, and muscle bundle fibrillation. The motor neurons in ALS patients gradually deteriorate, making physical activity increasingly challenging. Huntington’s disease (HD) is a rare autosomal dominant genetic disease caused by cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) amplification of the Huntington gene encoding multiglutamine. HD eventually leads to neurological dysfunction and degeneration [3], with the clinical manifestations usually including involuntary dance-like movements. HD patients are usually middle-aged and exhibit motor, cognitive and psychiatric symptoms, with the course of disease characterized by progressive deterioration. Epilepsy is a common neurological disorder characterized by persistent susceptibility to seizures, with neurobiological, cognitive, psychological and social consequences [4, 5]. The pathogenic process induces physiological and structural changes in the brain, leading to increased susceptibility to seizures and an increased risk of spontaneous recurrent seizures (SRS) [6]. Epilepsy can lead to social cognitive impairment and mental disorders, thereby reducing the quality of life and survival of patients. Stroke can be divided into ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Ischemic stroke is caused by interruption of the cerebral blood supply, and accounts for about 80% of stroke cases. Hemorrhagic stroke is caused by cerebral vascular rupture or abnormal vascular structure. It can be divided into subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). Compared with ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke has higher mortality and morbidity due to severe neuronal death. Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide. The high morbidity and disability from stroke are extremely detrimental to human health and life [7]. Ferroptosis is distinct from cell necrosis, apoptosis, and autophagy [8]. It is primarily characterized by an intact plasma membrane, increased mitochondrial membrane density, diminished or absent mitochondrial cristae, increased release of oxidized polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), and excessive accumulation of lipid-reactive oxygen species. A selective, lethal small molecule called erastin was first shown in 2003 to induce cell death in tumorigenic cells expressing rat sarcoma (RAS), an activator of this phenomenon [9]. Ferroptosis can be inhibited by iron (Fe) chelators and antioxidants. Ever since the concept of ferroptosis was first proposed, a multitude of studies have highlighted the significant role of this process in the pathogenesis and progression of various human diseases, particularly those of the nervous system [10]. This unique mode of cell death is driven by Fe-dependent phospholipid peroxidation and is regulated by a variety of cellular metabolic processes, including redox homeostasis, Fe metabolism, mitochondrial function, and the metabolism of amino acids, lipids, and carbohydrates [11]. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of ferroptosis could potentially lead to the development of preventive and therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative diseases [12].

The concept of ferroptosis was first introduced by Dixon in 2012 [13]. It was described as a form of regulated cell necrosis induced primarily by Fe-dependent oxidative damage [14]. This mode of cell death is distinct from apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy in terms of morphology, biochemistry, and genetics. For instance, cells undergoing ferroptosis exhibit an increased density of mitochondrial membrane, and a reduction in mitochondrial volume. Concurrently, the structure of mitochondrial cristae disappears and the outer membrane ruptures. However, the nuclear volume of cells undergoing ferroptosis remains largely unchanged, and the chromosomal structure within the nucleus is preserved [15]. In cell death modes such as apoptosis and autophagy, the cells rupture, release their contents, and potentially trigger an inflammatory response. In contrast, the primary mechanism of ferroptosis involves the catalysis of unsaturated fatty acids that are highly expressed on the cell membrane. This occurs under the influence of divalent Fe (Fe2+) or esterase oxygenase [16]. The catalysis induces lipid peroxidation and subsequent cell death. Fe and lipid peroxidation are the two major components necessary for ferroptosis [17]. Some researchers have proposed that the accumulation of lipid peroxides ultimately leads to ferroptosis, with Fe ions serving merely as a key regulator in the process of ferroptosis. Additionally, reduced expression of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), the core regulatory enzyme of the antioxidant system (glutathione system), also plays a crucial role in ferroptosis [18] (Fig. 1, Ref. [19]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Signaling pathways in ferroptosis. Ferroptosis is an oxidative cell death process that can be controlled at multiple levels. Briefly, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) for ferroptosis can be initiated by Fe-dependent Fenton reactions, mitochondrial dysfunction, or increased activity by the NOX family. The intracellular Fe level is affected by various Fe storage and export proteins. The production of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) and subsequent lipid peroxidation play a major role in promoting ferroptosis (Reproduced with permission from Liu J, et al., Signaling pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis; published by The FEBS Journal, 2022 [19]). TF, transferrin; LTF, lactotransferrin; NOX, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases; GSH, glutathione; PUFA-PL, polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipid; PUFA-ePL, polyunsaturated fatty acid ether phospholipid; ALOX, lipoxygenase; POR, cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase; mtDNA, mitochondrial DNA; gDNA, genomic DNA; MDA, malondialdehyde; CTSB, cathepsin B; ATM, ataxia telangiectasia mutated; ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein.

Fe is the most abundant transition metal element in the human body and has crucial biological roles in oxygen transport, electron transfer, gene regulation, and macrophage polarization [20]. In biological systems, Fe exists predominantly in protein-bound forms such as hemoglobin, myoglobin, transferrin (Tf), and ferritin (FT) [21]. Fe plays a pivotal role in ferroptosis, including the formation of lipid peroxidase and catalytic intracellular redox reactions. Two ionic forms of Fe exist in the cell: ferrous Fe (Fe2+) and ferric Fe (Fe3+). The absorption, transport, storage, and utilization of these ions can influence the regulation of ferroptosis [22]. Under physiological conditions, one Tf molecule can bind two Fe3+ ions [23]. Tf binds to its high-affinity receptor 1 (transferrin receptor 1, TfR1) at the cell surface to form a complex that is internalized into endosomes. In the endosome, the six transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostat3 (STEAP3) reduces Fe3+ to Fe2+, which is then transferred into the cytoplasm via divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT 1) [24]. A small amount of Fe2+ forms an unstable, labile iron pool (LIP). LIP is at the core of Fe homeostasis and the regulation network. Fe2+ is transported to the outside of the cell by the action of membrane ferritransporter (FPN) [9]. Ferroptosis can be mediated by controlling FPN, thereby altering intracellular Fe2+ levels. Under normal conditions, Fe metabolism is in a balanced state [25]. Free cytoplasmic Fe2+ is introduced into FT and reoxidized to Fe3+ by the action of Fe oxidase present in isoferritin H. In eukaryotic cells, FT is a globular protein composed of 24 independent subunits that contain a defined amount of Fe3+[26]. FT is an Fe storage protein that occurs widely in living organisms. Its biological function is mainly in the participation of Fe metabolism, where it plays an important role in maintaining Fe balance and cellular antioxidants. The unique cage-like structure of FT allows it to store up to 4500 Fe atoms in its inner cavity. FT autophagy is a selective form of autophagy that helps to initiate the degradation of FT leading to ferroptosis. This triggers unstable iron overload (IO), lipid peroxidation, membrane damage, and cell death [27]. Mechanistically, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increases the expression of nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) and the intracellular Fe2+ level, but decreases the level of FT. NCOA4-mediated FT autophagy transfers intracellular FT to autophagolysosomes for degradation and the release of free Fe. Hence, NCOA4 can interact directly with FT and degrade it in a FT autophagy-dependent manner, subsequently releasing large amounts of Fe. Cytoplasmic Fe2+ induces the expression of ferriomycin (SFXN1) in the mitochondrial membrane. SFXN1 then transports cytoplasmic Fe2+ into the mitochondria, where it generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and causes ferroptosis [26]. Ferroptosis is therefore an autophagy process, and NCOA4-mediated FT autophagy supports ferroptosis by controlling cellular Fe homeostasis [28]. The depletion of FT and Tf leads to the accumulation of cellular Fe, which in turn produces ROS via the Fenton reaction, thus promoting cell ferroptosis.

Excess intracellular Fe2+ leads to the gradual accumulation of Fe-dependent

lipid ROS, and eventually to the induction of ferroptosis [29]. At present, there

are three known pathways involved in the production of Fe-dependent lipid ROS in

ferroptosis [30]. First, due to its instability and high reactivity, Fe2+

combines with H2O2 to form a mixture [31] that oxidizes organic matter

(alcohols, esters, etc.) via the Fenton reaction to generate ROS. The

intracellular localization changes from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma

membrane, where the PUFA reaction produces a large amount of ROS that leads to

cell death [32]. This is a key step that drives ferroptosis and is currently also

a very active area of research. Second, lipid auto-oxidation produces ROS, which

is controlled by an Fe-catalyzed enzymatic pathway [33]. Third, an Fe-containing

lipid synthase oxidizes arachidonic acid (AA) to produce ROS. The transfer of Fe

from outside the cell to inside the cell is regulated by iron-response element

binding protein 2 (IREB2) [34]. Knockout of the corresponding IREB2 gene

can significantly reduce ferroptosis [35], thereby demonstrating the

Fe-dependence of ferroptosis. Increased cellular Fe uptake via TfR1 reduces Fe

overload through endosomal circulatory storage and the promotion of ferroptosis

[36]. Inhibition of IREB2 has been shown to reduce the incidence of ferroptosis

[37], and heat shock protein

The specific mechanism by which ferrous ions expedite ferroptosis remains elusive. Current evidence suggests that compounds able to bind Fe to form a stable complex (Fe chelators) inhibit Fe ions from donating electrons to oxygen, thereby promoting the formation of ROS during ferroptosis [39]. Lipophilic Fe chelators and the Fe chelator deferoxamine (DFO) have attracted attention due to their distinct targets in ferroptosis [40]. The lipoxygenase (LOX) family, functioning as an Fe-dependent lipid reactive oxygen species (L-ROS) channel, can inhibit the degradation of glutathione (GSH) or GPX4 to block ferroptosis [41]. The active site of LOX requires the presence of Fe to exert catalytic activity, while the Fe chelating agents DFO and deferoxone can inhibit ferroptosis by extracting Fe from LOX [42]. Oxidized PUFA is a crucial component of LOX, promoting the further oxidation of Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) into their hydroperoxide intermediates. The formation of soluble or lipid-free radicals instigates the initial cleavage or amplification of PUFA. ROS can induce lipid peroxidation by reacting with PUFA in the lipid membrane [43], with the level of PUFA being inversely proportional to lipid peroxidation. Based on the interaction between the membrane permeability of lipophilic Fe chelators and chelating Fe pools, PUFA can be produced in intracellular free Fe pools with ‘redox activity’ and can be inhibited by lipophilic Fe chelators [44].

Currently, the majority of ferroptosis mechanisms being investigated are associated with ROS [45]. The accumulation of intracellular ROS serves as a direct catalyst for ferroptosis, and numerous sources of lipid ROS can induce ferroptosis [46]. Fe2+ generates ROS through the Fenton reaction. The inactivation of GPX4 caused by GSH depletion, and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent lipid peroxidation, can also lead to ROS accumulation. When GSH deficiency leads to inactivation of GPX4, the cells are primarily characterized by increased Fe-dependent lipid ROS production and PUFA consumption on the lipid membrane [47]. PUFAs are highly sensitive to oxidation by lipoxygenase and ROS, leading to the formation of lipid hydroperoxides (L-OOH). Under physiological conditions, GPX4 can reduce L-OOH to lipid alcohols (L-OH) and prevent the formation of lipid free radicals. When GSH deficiency leads to GPX4 inactivation, L-OOH forms toxic lipid free radicals (such as lipid alkoxy radica (L-O.)) with the participation of Fe ions. These free radicals simultaneously transfer protons to surrounding PUFAs, thus spreading oxidative damage from one lipid to another and ultimately leading to oxidative cleavage of PUFAs. When GPX4 is inactivated, the consumption of arachidonic acid (AA) can also induce ferroptosis [48]. Two lipid metabolism-related genes have been described: lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3), and acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4). Ferroptosis is caused by ‘2’ ferroptosis inducers (FINs), such as Ras-selective lethal 3 (RSL3) and diphenyleneiodonium chloride 7 (DPI7) [49]. ACSL4 mediates the acylation of AA, while LPCAT3 catalyzes the acylation of AA to form membrane phospholipids, which can then transmit ferroptosis signals after oxidation [50]. AA-containing phosphatidylethanolamine is a key phospholipid that is oxidized and causes ferroptosis [51].

The reducing agent NADPH can maintain the reduced state of GSH and ensure the

normal function of GPX4. Decreased NADPH activity interferes with the antioxidant

effect of the GSH/GPX4 system, resulting in the accumulation of ROS [52]. In

microglia, Fe ions can promote NADPH oxidase (NOX)-mediated ROS production,

resulting in a significant decrease in the number and activity of neurons [53].

Pretreatment with the NOX2 and NOX4 inhibitors GSK2795039 and GKT137831

significantly reduced ROS production and neuronal damage [54]. NOX is also

associated with NMDA receptor (NMDAr) activation and superoxide production

through a mechanism closely associated with glutamate neurotoxicity. This

mechanism is also involved in epilepsy and stroke. Excitatory toxicity was

originally used to refer to rapid neuronal death caused by glutamate receptor

activation, often attributed to Ca2+ influx via NMDAr. This resulted in the

production of nitric oxide by neuronal nitric oxide synthase, and mitochondrial

production of superoxide, which react to form highly cytotoxic peroxynitrite. The

superoxide produced by NMDAr activation originates mainly from NOX, not from

mitochondria. Neurons also produce superoxide during NMDAr stimulation, and the

removal of superoxide prevents excitotoxic death. NOX is a multisubunit enzyme

that uses NADPH-derived electrons from one side of the membrane to produce

superoxides on the other side. The production of superoxide by NOX requires

glucose, as this is a necessary substrate for the pentose phosphate shunt to

regenerate NADPH from NADP+. In contrast, superoxides produced by mitochondria

can be fueled by pyruvate or other non-glucose substrates. NMDAr and NOX

signaling pathways involve Ca2+ influx, phosphoinositol-3-kinase, and

protein kinase

System Xc– is a reverse amino acid transporter formed by the disulfide bond linkage of solute carrier family-7 member-11 protein with solute carrier family-3 member-2 protein [56]. This transporter mediates the exchange of cystine and glutamate. It serves as a crucial antioxidant system within the cell and establishes a functional pathway for the ferroptosis inhibitor erastin. System Xc– facilitates the exchange of extracellular cystine (Cys2) with intracellular glutamate at a 1:1 ratio. Cystine is synthesized into glutathione (GSH) under the catalysis of glutamate cysteine ligase (GCS) and glutathione synthetase (GSS) [57]. This pathway suggests that upon uptake, cystine is reduced to cysteine (Cys), which subsequently participates in the synthesis of GSH. The rate-limiting substrate for GSH synthesis is cysteine [58], while the rate-limiting enzyme is GCS [59]. Inhibition of GCS enzyme activity by buthionine sulfoxide interferes with GSH synthesis and induces cell death [60]. Fe chelators can mitigate cell death caused by thiophanate sulfoxide amine, indicating that inhibition of GSH synthesis can trigger ferroptosis [61]. GSH is a vital antioxidant in the human body and regulates normal physiological functions within a standard concentration range. Excessive GSH concentrations can lead to neurotoxicity [62]. When System Xc– is inhibited, the influx of cystine into the cell decreases, leading to a reduction in Cys levels and subsequently a reduction in GSH synthesis [63].

Glutathione peroxidases (GPXs) are a phylogenetically-related class of enzymes, with GPX4 being a member of this family [64]. As a reducing agent, GSH is an indispensable cofactor for GPX4 to manifest its antioxidant effects [65]. GPX4 catalyzes the conversion of GSH to oxidized glutathione (GSSG), while reducing intracellular toxic lipid peroxides (L-OOH) to their corresponding non-toxic lipid alcohols (L-OH). This process prevents the formation of Fe-dependent, highly reactive lipid alkoxy radicals (L-O.) derived from L-OOH. Consequently, GPX4 activity is vital for maintaining intracellular lipid homeostasis [66]. The inactivation of GPX4, or the silencing of genes related to GPX4 expression, results in the accumulation of lipid ROS and ultimately leads to ferroptosis [67]. Cells with down-regulated GPX4 expression were found to be more susceptible to ferroptosis, whereas cells with up-regulated GPX4 expression were resistant to ferroptosis [68]. GSH reduces ROS and active nitrogen species through the action of GPXs [69]. Glutathione-disulfide reductase (GSR) catalyzes the reduction of GSSG to GSH using electrons provided by NADPH/H+. Apart from its antioxidative role, GPX4 also plays a significant role in growth processes [70]. Chemical proteomics studies have confirmed that RSL3 is an affinity reagent for GPX4, and the triggering of ferroptosis by RSL3 has been speculated to depend on this affinity. The blocking of GPX4 activity by RSL3 is one of the reasons for RSL3-triggered ferroptosis [71]. However, the specific mechanism of action of RSL3 and other ‘class 2’ FINs on GPX4 remains unclear.

The promotion of mitochondrial ferroptosis can be attributed to ROS generated by

mitochondrial respiration, which inflict damage upon enzymes in the mitochondrial

respiratory chain complex. The dysregulation of mitochondrial respiration has two

primary causes. Firstly, the inhibition of SLC7A11 or cystine deprivation can

result in a large reduction in GSH, thereby diminishing its capacity to scavenge

ROS [72]. Secondly, the inactivation of SLC7A11 can result in cellular glutamate

accumulation and its subsequent conversion to

The lysosome is an acidic, membrane-bound organelle that has the capacity to instigate ferroptosis. This can occur via three distinct pathways [77]. Firstly, lysosomes serve as a repository for Fe ions. Ablation of the lysosomal protein saponin results in the accumulation of lipofuscin, which mediates the build-up of lysosomal Fe and ROS, thereby precipitating neuronal ferroptosis [78]. The second pathway involves the activation of autophagy. Macroautophagy is a lysosome-dependent degradation pathway that has been implicated as an autophagy-dependent form of cell death [79]. The third pathway involves the release of lysosomal cathepsins.

Both the upstream and downstream mechanisms by which exosomes regulate ferroptosis are not entirely elucidated. Exosomes have been reported to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis. Conversely, exosomes can exert significant therapeutic effects on cardiovascular diseases, nervous system disorders, and liver diseases by inhibiting ferroptosis [80].

Ferroptosis is considered to have an important relationship with neurological diseases, especially neurodegenerative diseases. A multitude of studies have highlighted the close relationship between ferroptosis and neurodegenerative diseases [81]. Table 1 (Ref. [82, 83, 84, 85, 86]) lists the relationship between several major neurodegenerative diseases and the ferroptosis pathway and related targeted drugs. Inhibition of GPX4 activity in forebrain neurons of mice induces an increase in ferroptosis. This is accompanied by lipid peroxidation and cognitive dysfunction, thereby establishing a connection between ferroptosis and neurodegenerative diseases [87] (Fig. 2, Ref. [88]).

| Neurodegenerative diseases | Major ferroptosis pathways | Targeted drugs |

| AD | Amyloid precursor protein (APP) can regulate the level of Fe transporters in the membrane of neurons to promote the output of Fe ions. When the APP membrane function is impaired, the Fe ion output is obstructed, leading to an increase in the neuronal Fe ion content. Studies have demonstrated that elevated glutamate in AD patients is associated with System Xc– dysfunction. Aberrant glutamate in ferroptosis is also predicated on System Xc– dysfunction. Lipid peroxidation is intrinsically linked to the onset of ferroptosis, with lipoxygenase (LOX) playing a pivotal role in mediating this process. Phospholipids, particularly those containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) components, are susceptible to oxidation induced by LOX-mediated free radicals. This oxidation subsequently leads to the disintegration of lipid bilayers, thereby promoting ferroptosis. | Memantine (with anticholinesterase effect), donepezil (increasing the concentration of acetylcholine in the brain), kabbalatine (reduces the hydrolysis of acetylcholine released by nerve cells), galantamine (increase the content of acetylcholine) and oxiracetam (promotes protein and nucleic acid synthesis). |

| PD | Ferroptosis has been implicated in PD, with clinical investigations revealing a marked increase in the Fe concentration within the substantia nigra of PD patients [82]. This elevated Fe level can trigger an increase in hydroxyl radicals and dopamine oxidation, thereby creating an oxidative milieu that precipitates damage to dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Moreover, genetic aberrations linked to brain Fe metabolism are frequently implicated in the etiology of PD. | Levodopa (supplement of dopamine in the brain), amantadine hydrochloride (can improve cognitive impairment), entacapone and carbidopa (can be converted into dopamine in the brain), ropinirole (reversible central nervous system dopamine receptor agonist) and piribedil (can alleviate bradykinesia). |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) | Although the precise etiology of ALS remains unknown [83], ALS patients exhibit elevated Fe concentrations in the spinal cord and FT accumulation in motor neurons. Concurrently, enhanced lipid peroxidation is observed in motor neurons. | Riluzole (by reducing the level of glutamate to reduce the damage of motor neurons), edaravone (inhibition of lipid peroxidation), baclofen, diazepam (these two are often used to control spasm), trihexyphenidyl, amitriptyline (can alleviate the difficulty of swallowing saliva), sodium phenylbutyrate and taurine diol (reduce neuronal cell death). |

| HD | Patients with HD typically have lower plasma glutathione (GSH) levels and reduced glutathione peroxidase (GPX) activity in red blood cells, both of which are strongly associated with ferroptosis. Moreover, the application of Fer-1 and Fe chelating agent also resulted in good protective effects in neurons [84]. | Benzenequine (symptomatic treatment of hyperactive dyskinesia), deuterated butylphthalide (reversible, high-affinity presynaptic neuron granule vesicles to absorb monoamine inhibitors), valbenazine capsules (reduce presynaptic dopamine levels), olanzapine (can be used for delayed extrapyramidal dyskinesia), risperidone (for the treatment of acute and chronic schizophrenia), tiapride (also has analgesic effect), baclofen (relieve muscle rigidity and painful spasm) and benzodiazepines (the most widely used sedative hypnotics). |

| Epilepsy | The main pathogenic mechanism of epilepsy in various etiologies is oxidative stress (OS). Significant dysregulation of three key markers of ferroptosis have been found: a sustained increase in 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE, a major by-product of lipid peroxidation), a significant reduction in GSH levels, and partial inactivation of GPX4, which is a mediator of lipid peroxidase detoxification. High levels of extracellular glutamate (Glu) inhibit System Xc− in the GSH-dependent ferroptosis pathway, leading indirectly to decreased GPX4 activity, increased accumulation of intracellular lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS), and ultimately to cell death. Therefore, Glu may be an inducer of ferroptosis in epilepsy [85]. | Carbamazepine (to reduce abnormal discharges by regulating the balance of neurotransmitters), phenobarbital (to stabilize the epileptic state by enhancing the inhibitory process in the brain), sodium valproate (to block synaptic transmission media), lamotrigine (to reduce synaptic site excitability) and levetiracetam (a new drug). |

| Brain ischemia and/or stroke | Ferroptosis occurs when blood that is rich in free Fe and ferritin (FT) enters the brain parenchyma through the damaged blood-brain barrier (BBB) during hemorrhagic stroke and late cerebral ischemia. The Xc− system regulates intracellular GSH to eliminate excess hydroxyl peroxides, thus reducing Glu uptake and increasing its release after stroke. This leads to an elevated extracellular Glu concentration and subsequent excitatory toxicity. These events block the reverse transfer function of the Xc− system and cause cell death [86]. | Clopidogrel Hydrogen Sulfate Tablets (used to prevent and treat heart, brain and other arterial circulatory disorders caused by high platelet aggregation), Aspirin Enteric-coated Tablets (anti-platelet aggregation) and Atorvastatin Calcium Tablets (lipid-lowering by inhibiting cholesterol synthesis). |

| Brain injury | ROS contributes to protein and lipid oxidation, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammatory responses, all of which mediate secondary brain damage after ischemic stroke. | Mannitol (most commonly used, can be dehydrated to reduce intracranial pressure). |

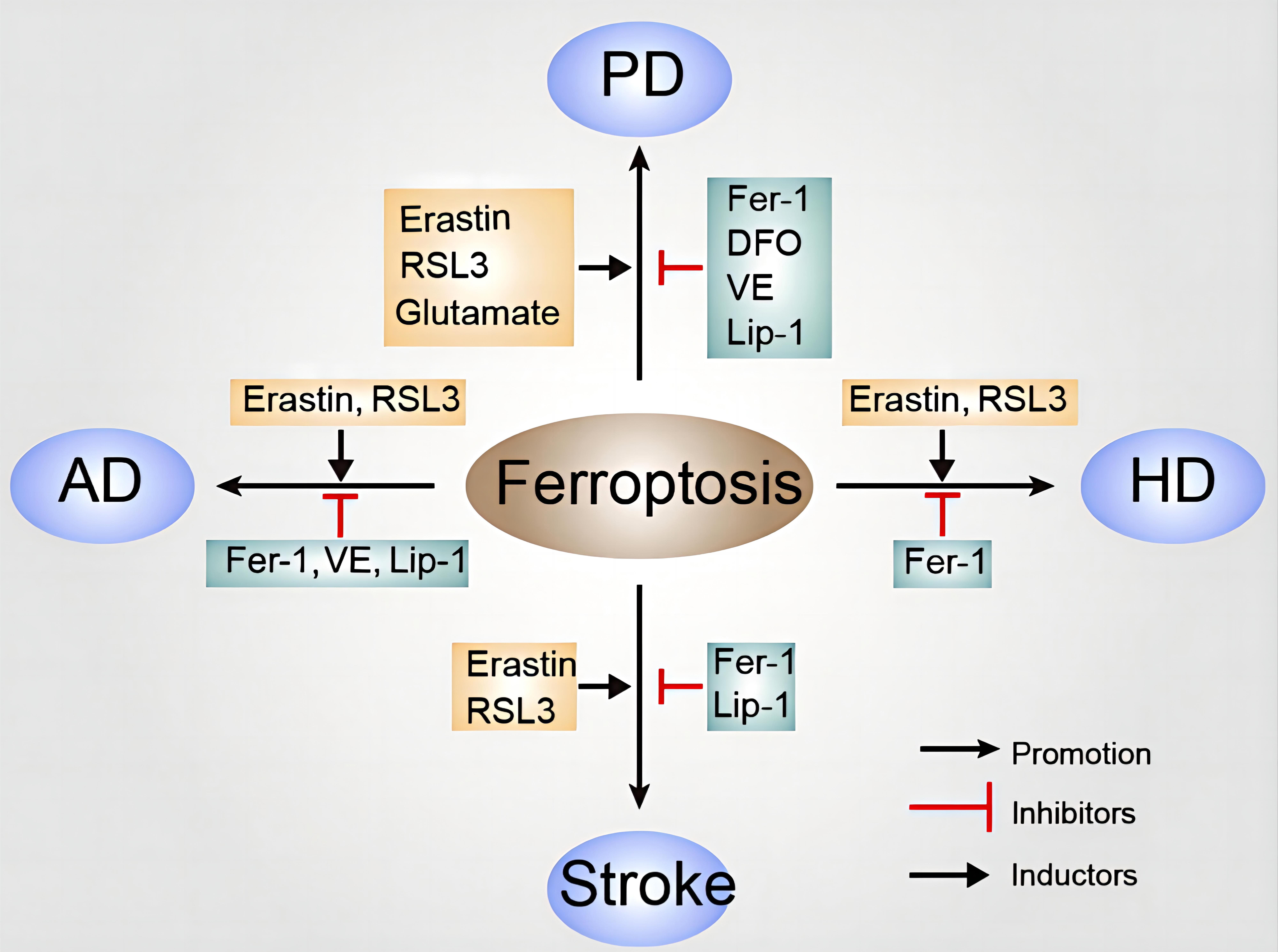

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The role of ferroptosis in neurodegenerative diseases. Various inducers and inhibitors of ferroptosis in different neurodegenerative diseases are shown. Inducers of ferroptosis in AD, inhibitors of ferroptosis in AD; inducers of ferroptosis in PD, inhibitors of ferroptosis in PD; inducers of ferroptosis in HD, inhibitors of ferroptosis in HD; inducers of ferroptosis in stroke, inhibitors of ferroptosis in stroke (Reproduced with permission from Dang X, et al., Correlation of Ferroptosis and Other Types of Cell Death in Neurodegenerative Diseases; published by Neuroscience Bulletin, 2022 [88]). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; HD, Huntington’s disease; RSL3, Ras-selective lethal 3; DFO, deferoxamine; VE, vitamin E; Fer-1, ferrostatin-1; Lip-1, liproxstatin-1.

AD is an age-associated neurodegenerative disorder and a primary cause of

cognitive deterioration in the elderly population [89]. This disease has emerged

as a significant concern, impacting the health and quality of life of many

individuals. Epidemiological investigations have revealed that the incidence of

AD is as high as 10% in individuals aged over 65 years. The clinicopathological

hallmarks of AD include senile plaques formed by extracellular

One of the characteristic pathological features of AD is the extracellular

deposition of A

Glutamate excitotoxicity is also a significant pathogenic factor in AD.

Additionally, trypsin can bind to protease-activated-receptor 2 (PAR-2), activate

extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK) in the cortical neurons of AD

mice, and counteract glutamate excitotoxicity. The Fe ion inducer erastin acts on

the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway in tumors and can

significantly increase phosphorylated ERK1/2. Brain tissue contains a substantial

amount of unsaturated lipids, which are more susceptible to ferroptosis. Elevated

levels of free radicals in the brain of AD patients create favorable conditions

for lipid peroxidation [96], and lipid peroxide levels are significantly

increased in brain regions that are rich in A

Plasma ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a multicopper oxidase with four active copper ions. Cp can oxidize Fe2+ to Fe3+, and reduce oxygen to water [98]. Moreover, Cp gene mutation and protein dysfunction are a significant cause of AD. Cp is involved in the binding of Fe3+ to transferrin and its transport in plasma. Reduction of Fe excretion by cells leads to excessive Fe2+ in the labile Fe pool and hence the production of hydroxyl radicals through the Fenton reaction. This in turn leads to ferroptosis and enhances the neuroinflammatory response through ROS, thus forming a complex cycle of exacerbation in AD patients.

Another pathological feature of AD is the excessive phosphorylation of Tau protein leading to the formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) in neurons. Tau protein is associated with the stability of microtubules [99]. When the level of Tau phosphorylation is high, it first assembles into pairs of spiral filaments, and then aggregates and precipitates to form NFT. This causes microtubules to decompose, leading to neuronal death. Tau protein can regulate cellular Fe outflow through cell membrane transport. High phosphorylation and aggregation of Tau protein may impede this outflow and cause accumulation of neuronal Fe, thus further promoting the formation of NFT and creating a vicious circle. The imbalance of brain Fe homeostasis is closely related to Tau protein and NFT. Fe can regulate the phosphorylation of Tau protein and induce the accumulation of abnormally phosphorylated Tau protein [100]. Excessive Fe also promotes the phosphorylation of Tau protein, thereby promoting the production of NFT and ultimately leading to the dysfunction of neurons and synapses. Knockout of the Tau gene in rats can has been reported to produce age-dependent Fe accumulation and brain atrophy [101]. Abnormal deposition of Fe ions has also been observed in neuronal NFT. This may be related to the indirect involvement of Tau protein in the transmission of Fe ions in neurons during the pathogenesis of AD [102].

Recent studies have found that activation of lipoxygenase (LOX) is closely

associated with the pathogenesis of AD, influencing the metabolism of A

PD is a quintessential neurodegenerative disorder. It is characterized by the

degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and

the formation of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, primarily composed of aggregated

Epigenetic alterations associated with the functional loss of SLC7A11 have

also been identified in PD patients. This functional impairment leads to a

reduction in cystine uptake, which subsequently causes a decrease in cysteine

levels and culminates in the diminished production of GSH, thereby abrogating the

ability of GPX 4 to mitigate lipid peroxidation [107]. Furthermore, the loss of

DJ-1 function can compromise cysteine production via the sulfur transfer pathway,

resulting in decreased GSH synthesis. The PLA2G6 mutation inhibits hydrolysis

of the lipid peroxide 15-HpETE-PE, which would otherwise be decomposed by

Fe2+ produced via the Fenton reaction or 15-LOX. Fe can

post-transcriptionally up-regulate the translation of

The neurodegenerative disorder ALS is characterized by muscle atrophy and weakness, culminating in respiratory failure. Empirical evidence suggests the Fe chelator Trientine can extend the lifespan of a humanized ALS mouse model. This finding highlights the potential to exploit ferroptosis as a therapeutic target in ALS management. Other studies have found elevated levels of lipid peroxidation in the red blood cells of ALS patients and reduced GSH levels. The latter could exacerbate the degeneration of motor neurons in ALS [108].

An extended CAG triplet repeat sequence was found in the coding region of chromosome 4 in an HD patient and was originally labeled IT-15. This gene was later renamed HTT, and its protein product referred to as “Huntington’s protein”. Researchers have since focused on studying wild-type and mutant HTT proteins (mHTT), including elucidation of the mechanism by which mHTT causes HD, as well as the development of therapies that target mHTT and their biological effects [109]. mHTT expression leads to Fe accumulation in the brain of HD patients. Therefore, HTT levels and/or glutamine amplification within HTT are important regulators of Fe status. We previously showed that Fe does not directly interact with n-terminal HTT fragments, suggesting the effect of HTT on Fe is mediated by downstream effects in the Fe homeostasis pathway. Analysis of Fe homeostasis in R6/2 HD mice revealed decreased levels of iron reactive protein (IRP1 and 2), resulting in decreased TfR expression and increased levels of the neuronal Fe export protein ferritransporter (FPN). These changes were consistent with a compensatory response to an increase in the unstable Fe reservoirs within neurons [110]. The expression of N-terminal fragment containing mHTT-amplified polyglutamine (HTTQ94) can promote ACSL4-dependent and -independent ferroptosis. In addition, ALOX5 was found to be the main factor required for ACSL4-dependent ferroptosis induced by HTTQ94. Although ALOX5 is not required for the ferroptosis response triggered by common inducers such as erastin, the loss of ALOX5 expression prevents ferroptosis induced by HTTQ94-mediated ROS. ALOX5 is also required for HTTQ94-mediated ferroptosis in neuronal cells with high levels of glutamate. Thus, ALOX5 is critical for mHTT-mediated ferroptosis and may be a potential new target for HD [111]. Mitochondrial bioenergy dysfunction is also associated with neurodegeneration in HD. The brain tissues of human HD patients and mouse models of HD (R6/2 at 12 weeks and YAC128 at 12 months) showed elevated mitochondrial Fe, increased expression of the Fe-uptake protein mitoferrin 2, and decreased expression of the Fe-sulfur cluster protein frataxin. The mitochondria-enriched portion of mouse HD brain showed defects in membrane potential and oxygen uptake, as well as increased lipid peroxidation. In addition, the membrane-permeable, Fe-selective chelating agent deferrone (1 µM) could rescue these effects in vitro, but not hydrophilic Fe and copper chelating agents. This demonstrates the importance of Fe as a mediator of mitochondrial dysfunction and damage in a mouse model of human HD, and suggests that targeting the Fe-mitochondrial pathway may be protective [112].

During acute seizures, excessive ROS are produced due to mitochondrial dysfunction and/or increased NOX activity. The targeting of oxidative stress (OS), and specifically the antioxidant transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf-2), showed beneficial disease-modifying effects in models of acquired epilepsy by delaying the onset and progression of seizures. It does this by providing ROS to remove antioxidants, or by enhancing the endogenous antioxidant system. These effects may be facilitated by proteins involved in the production and circulation of GSH, the main intracellular antioxidant. Recent evidence from focal cortical dysplasia and nodular sclerosis clusters of congenital epilepsy suggests that OS and Fe metabolism are closely related and may work synergistically to exacerbate epileptic cell dysfunction and damage. Thus, high concentrations of unbound Fe2+ can act as a catalyst in Haber-Weiss and Fenton reactions to increase the potency of hydrogen peroxide to the more reactive ROS, thereby promoting cell dysfunction and death [113]. Direct and indirect evidence for neuronal ferroptosis in epileptic seizures has been obtained in several animal models of epilepsy. Importantly, the inhibition of ferroptosis has a neuroprotective effect [114]. The ferroptosis inhibitor FERstatin 1 (Fer-1) shows protective effects against acute seizures and memory loss. Fer-1 also inhibits ferroptosis-related markers in the hippocampus, including glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity and the expression of 4-HNE protein. This suggests that Fer-1 may have a powerful therapeutic effect on seizures and cognitive impairment following post-traumatic epilepsy (PTE)-induced brain injury. It could therefore be a promising drug for the treatment of patients with PTE [115]. In addition, it has been suggested that uncontrolled repetitive generalized tonic-clonic seizures (GTCS), as described in refractory epilepsy, can cause hyperhypoxic stress in the heart. This induces hemosiderin-containing accumulation, as in iron-overload cardiomyopathy (IOC), and may be a hidden mechanism for the development of late arrhythmias leading to sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) [116]. Ferroptosis has also emerged as an important neuronal death mechanism in temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE), which is mainly affected by lipid accumulation and OS. REDOX changes in different organelles may have different pathophysiological significance during the course of Fe-death-related diseases. As a key organelle involved in ferroptosis, structural damage and the dysfunction of mitochondria can disturb energy metabolism and disrupt the excitatory/inhibitory balance, thereby increasing the susceptibility to seizures [117]. In addition, bioinformatics analysis was used to construct the complex network, drug network, mRNA-miRNA network, and transcription factor network for three key genes, namely HIF1A, TLR4 and CASP8. This provides a framework for exploring potential regulatory targets and possible mechanisms of ferroptosis in epilepsy, thereby providing new insights into the treatment of epilepsy [118].

Recent studies have highlighted a strong link between ferroptosis and stroke. Intracellular Fe overload is pivotal to ferroptosis. Ferroptosis has been shown tp be involved in neuronal death after ICH in vitro and in vivo, and it also plays an important role in early brain damage after SAH. Ischemic stroke involves two important events, ischemia and reperfusion injury (IRI), which can result in severe cell damage and poor prognosis. After ischemia, Fe accumulation occurs due to the inhibition of tau expression. The excess Fe flows into brain parenchyma via the damaged blood-brain barrier (BBB) where it promotes ROS production through the Fenton reaction. This subsequently promotes nuclear, proteome and membrane damage, and eventually triggers cell death by ferroptosis [119]. Following severe ischemic and hypoxic brain injury, Fe deposition increases in the basal ganglia, thalamus, periventricular, and subcortical white matter areas. In a mouse model of ischemic stroke, GSH levels in neurons were found to be significantly reduced, lipid peroxidation enhanced, and GPX4 activity reduced. GSH and GPX4 are key regulators of ferroptosis and are strongly associated with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke. In addition, the use of ferroptosis inhibitors significantly improved the outcomes of patients with ischemic stroke. Studies of hemorrhagic stroke showed that n-acetylcysteine (NAC) inhibits the heme-induced ferroptosis of brain cells by neutralizing toxic lipids produced by AA-dependent ALOX5 activity. The early application of NAC after intracerebral hemorrhage can reduce neuronal mortality and improve prognosis. Other studies have reported a significant decrease in GPX4 expression in brain tissue 24 h after intracerebral hemorrhage. Increased GPX4 expression after intracerebral hemorrhage can significantly reduce neuronal dysfunction, brain edema, BBB damage, OS, and inflammatory damage. Application of the ferroptosis inhibitor Fer-1 after intracerebral hemorrhage also significantly reduces the degree of secondary brain injury [109]. In addition, neurovascular units (NVU) play a key role in the occurrence and development of ischemic stroke, and the function of NVU in stroke development can be modulated by activating or inhibiting ferroptosis [120].

Electroacupuncture therapy (EA) has been shown to inhibit the Xc-/GSH/GPX4 axis of the System after traumatic brain injury (TBI) by upregating the expression and activation of xCT, which is a major functional subunit of System Xc-. This confirms the notion of an EA effect in the treatment of TBI and provides theoretical support for its application in clinical practice [121]. Moreover, autophagy may be a viable therapeutic strategy for ischemic stroke, providing neuronal protection, reducing brain damage, and benefiting ischemic peripheral brain tissue [122].

Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation (NBIA) is a group of inherited neurological disorders characterized by significant

genetic heterogeneity and in which Fe atypically accumulates in the basal

ganglia. This results in changes in the brain visible by magnetic resonance

imaging, histopathological abnormalities, and neuropsychiatric clinical symptoms.

Mitochondria play an important role in NBIA disease, and an NBIA subtype with

altered mitochondrial proteins is considered to be a mitochondrial disease with

compromised oxidative phosphorylation. NBIA patients with defective

Pank2, Coasy, Pla2g6, or C19orf12 genes

exhibit widespread Fe accumulation in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra,

as well as mitochondrial disorders and neurological or motor disorders [123].

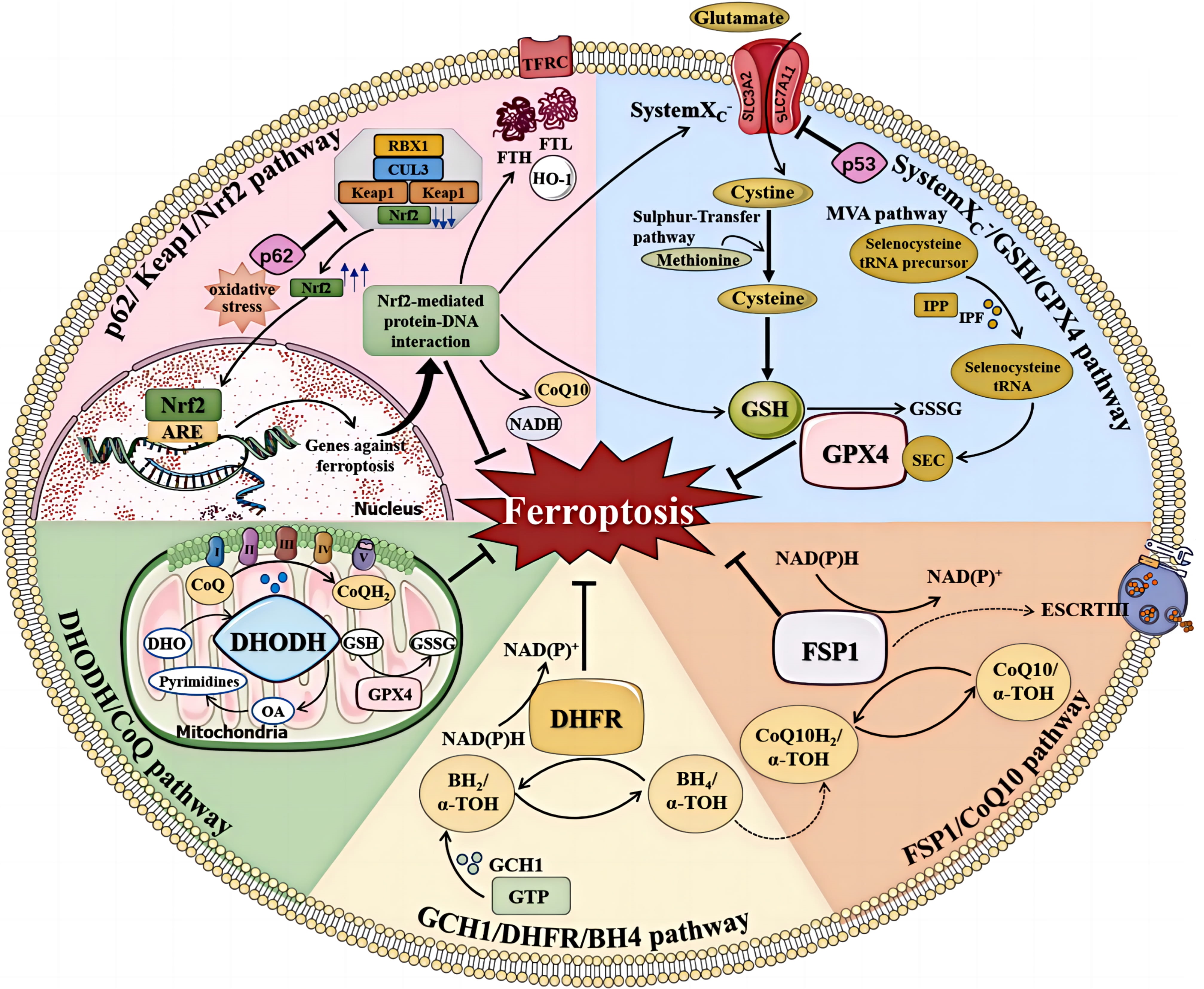

The Cyst(e)ine/GSH/GPX4 axis has long been recognized as a pivotal mechanism in the regulation of ferroptosis [126]. Inhibition of the cystine-glutamate antiporter, inhibition of GSH production, and reduced expression or activity of GPX4 can directly influence the initiation and progression of ferroptosis. GSH is a tripeptide composed of glutamic acid (Glu), cysteine (Cys), and glycine (Gly), in which the cysteine sulfhydryl functional group is an antioxidant. The cysteine for GSH can be obtained from methionine via the trans-sulfur pathway, or from extracellular cystine via System Xc–. The selenoprotein GPX4 is a key antioxidant enzyme that can directly reduce phospholipid peroxides to phospholipid hydrogen peroxide. The biosynthesis of GPX4 depends on co-translational incorporation of selenocysteine (Fig. 3, Ref. [127]) [128]. Cysteine and homocysteine inhibit ferroptosis in a GPX4-dependent manner. However, cysteine inhibition of ferroptosis is not associated with GSH synthesis, and homocysteine can inhibit ferroptosis through both non-cysteine and non-GSH pathways [129].

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The regulation of ferroptosis. Multiple pathways inhibit

ferroptosis by resisting oxidative stress and inhibiting lipid peroxidation.

These include the system Xc–/GSH/GPX4, FSP1/CoQ10, GCH1/DHFR/BH4,

DHODH/CoQ, and p62/Keap1/Nrf2 pathways (Reproduced with permission from Sun Y,

et al., Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Emerging Links to the Pathology of

Neurodegenerative Diseases; published by Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2022

[127]). TFRC, transferrin receptor; FTL, ferritin light chain; FTH, ferritin heavy chain; ARE, antioxidant response element; NAD(P)H, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (phosphate); IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; IPF, isopentenyl transferase; SEC, selenocysteine; DHODH, dihydroorotate dehydrogenase; DHO, dihydroorotate acid; OA, orotate; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; DHFR, dihydrofolate reductase;

Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), also known as ubiquinone, is a lipophilic metabolite

derived from the mevalonate pathway. Extramitochondrial CoQ10 is regenerated by

fibroblast-specific protein 1 (FSP1). FSP1 is thought to have a pro-apoptotic

role under certain conditions. It can also be transferred to the nucleus through

the cytoplasm or mitochondria, causing DNA degradation [130]. The FSP1/CoQ10

pathway acts in parallel with the System Xc–/GSH/GPX4 pathway. The

anti-ferroptosis function of FSP1 is based on its oxidoreductase activity and

uses NAD (P) H/H+ to reduce extra-mitochondrial CoQ10 to ubiquinol.

Panthenol can act as a strong radical and trap antioxidant to directly reduce

lipid radicals, or indirectly block lipid peroxidation through

GCH1/BH4/DHFR is a GPX4-independent mechanism of ferroptosis inhibition [131]. It is also an important part of the antioxidant system and can reduce the OS response. GCH1 is a cyclic hydrolase of guanosine triphosphate and a rate-limiting enzyme for BH4 synthesis. The GCH1-BH4-phospholipid axis acts as a major regulator of ferroptosis. It controls endogenous production of the antioxidant BH4, the abundance of CoQ10, and selectively inhibits phospholipid consumption containing two polyunsaturated fat acyl tails, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis. This demonstrates a unique ferroptosis protection mechanism that acts independently of the Cyst(e)ine/GSH/GPX4 mechanism [132]. BH4 is an effective free radical antioxidant, and as such is oxidized into dihydrobiopterin (BH2). BH2 can be regenerated into BH4 using NADPH as a hydrogen donor under the catalysis of dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR). BH4 biosynthesis is an important compensatory pathway under conditions of GPX4 inhibition [131]. Folic acid (FA) is important in the treatment of a variety of neurological diseases. The mechanisms for FA supplementation include inhibition of the transcription factor Sp1 (thereby inhibiting GCPII transcription), reducing Glu content, and blocking cell ferroptosis [133]. Liver cells treated with methotrexate (MTX) experience ferroptosis, and this can be attenuated by ferroptosis inhibitors [134]. MTX is a folate antagonist that inhibits the conversion of dihydrofolate into bioactive tetrahydrofolate, thereby inhibiting the synthesis of purine and pyrimidine by binding to DHFR in cells. DHFR is therefore an important regulator of ferroptosis. It regenerates oxidized BH4 with MTR to genetically or pharmacologically block DHFR function, and in conjunction with GPX4 inhibition can induce ferroptosis [131].

Dehydrogenase (DHODH) is one of the rate-limiting enzymes for the de novo synthesis of pyrimidine. It is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and catalyzes the oxidation of dihydroorotic acid to orotic acid. During this process, electrons are transferred to CoQ on the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby reducing it to the antioxidant panthenol and inhibiting ferroptosis in cells with low GPX4 expression [135].

Ferroptosis is characterized by lipid peroxidation mediated by an imbalance in

Fe homeostasis and a decrease in the reducing capacity of cells. The regulatory

network for ferroptosis is intricate and finely tuned. The development of small

molecule therapeutics that target the ferroptosis regulatory network has

demonstrated promising clinical potential and could emerge as a potent strategy

for the treatment of intractable diseases. Relevant studies have shown that the

Fe chelator therapeutic 5-YHEDA can cross the BBB via interaction with

low-density lipoprotein receptors and eliminate excess Fe and free radicals in

the brains of aged mice. In terms of treatment, Fer-1 in combination with

different cell death inhibitors can better prevent hemoglobin-induced cell death

in organotypic hippocampal slice cultures and human pluripotent stem cell-derived

neurons than any inhibitor alone. In a collagenase-induced mouse ICH model, a

combination of Fer-1, caspase3 inhibitor, and necrostatin-1 reduced cell death

more than any inhibitor alone [136]. Given the complex pathogenesis of

neurodegenerative diseases, single-target interventions often fail to yield

satisfactory outcomes, highlighting the need to explore multi-target

interventions for ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation. Lipids for peroxidation are

generated through lipid biosynthesis, with ACSL4 playing a pivotal role by

controlling Fe availability and also indirectly by up-regulating GPX4 via

selenium supplementation [137]. N2L is a novel fatty acid-nicotinic acid dimer

that reduces the production of various lipid peroxides, thereby offering a

potential therapeutic avenue for ferroptosis-related diseases. Traditional

medicinal plants have also provided novel insights into possible therapies for

neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, the dichloromethane extract from

sycamore leaves exhibits neuroprotective effects by enhancing the antioxidant

capacity of neurons and inhibiting ferroptosis. Moreover, flavonoid sterols are

under consideration as potential therapeutics for AD and other neurodegenerative

disorders. A series of lipophilic phenothiazine analogues have been synthesized,

with the most promising compound (1b-5b) demonstrating enhanced protective

effects against erastin and RSL3-induced ferroptosis. Idebenone is a CoQ10

analogue that is often used in the clinical treatment of AD. Recent studies have

shown that idebenone reduces lipid peroxidation and inhibits neuronal iron

apoptosis in rotenone-induced PD rat models by up-regulating GPX 4 [138]. In

addition, clinical trials have shown that DFO (40–60 mg/Kg/day) reduces the iron

saturation of blood transferrin. Trends in efficacy were observed in patients

with moderate to severe ischemic stroke (NIHSS

In addition to small molecule compounds, a novel disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative disorders is the utilization of human platelet lysates rich in neurotrophic factors. Recent evidence also supports the therapeutic potential of dietary interventions in treating neurodegenerative diseases. For example, a diet enriched in selenium can increase the expression of the selenoprotein GPX4, thereby inhibiting cellular ferroptosis. Studies have demonstrated that Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 (FSP1) can reduce CoQ10 to hydroquinone, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis. The fully reduced form of vitamin K (vitamin K hydroquinone, VKH2), similar to the reduced form of CoQ10, can function as a potent lipophilic antioxidant and effectively inhibit ferroptosis by scavenging oxygen free radicals in the lipid bilayer.

Neurodegenerative diseases are generally considered incurable and predominantly affect neurons in the human brain, leading to the deterioration of neuronal structure and function, and ultimately resulting in neuronal death. Current research is still in the exploratory phase, and a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms has yet to be fully realised. Further in-depth investigations are crucial to the development of therapeutic interventions for these diseases. As a novel form of cell death, ferroptosis is implicated in disease pathogenesis through increased Fe ion levels, oxidative stress, and glutamate excitotoxicity. Moreover, as an atypical mode of cell death, ferroptosis plays a role in various disease processes, with progressive delineation of the pathways and mechanisms involved. Although ferroptosis inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in certain disease models, the intricate relationship between different diseases and ferroptosis warrants further exploration. As a novel and promising therapeutic target, ferroptosis holds significant potential in future clinical management and in novel drug discovery for neurodegenerative diseases. At present, numerous aspects of ferroptosis remain enigmatic, necessitating extensive research to elucidate and clarify our understanding of cell death, and to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies for neurodegenerative diseases.

JZM: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing — Original draft preparation, Results interpretation, Writing — Reviewing and Editing. JWL, SYC, WXZ, TW, MC, and YY: Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Supervision, and Results interpretation. YLD, GQC, and ZJD: Results interpretation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing — Reviewing and Editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) [grant numbers 81602893], Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province [grant numbers ZR2015YL049, ZR2021MH218, ZR2022MH184], Shandong Province Medical and Health Technology Development Plan [grant numbers 202104020224, 202312010854], Shandong Province Traditional Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Plan [grant numbers Z-2023114], and Jinan Science and Technology Plan [grant number 202328074].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.