1 School of Health Sciences, Universidad Cardenal Herrera-CEU, CEU Universities, 46115 Alfara del Patriarca, Spain

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The relationship between polyphenols and autophagy, particularly in the context of aging, presents a promising avenue for therapeutic interventions in age-related diseases. A decline in autophagy is associated with aging-related affections, and an increasing number of studies suggest that this enhancement is linked to cellular resilience and longevity. This review delves into the multifaceted roles of autophagy in cellular homeostasis and the potential of polyphenols to modulate autophagic pathways. We revised the most updated literature regarding the modulatory effects of polyphenols on autophagy in cardiovascular, liver, and kidney diseases, highlighting their therapeutic potential. We highlight the role of polyphenols as modulators of autophagy to combat age-related diseases, thus contributing to improving the quality of life in aging populations. A better understanding of the interplay of autophagy between autophagy and polyphenols will help pave the way for future research and clinical applications in the field of longevity medicine.

Keywords

- autophagy

- aging

- polyphenols

Aging is a multifactorial process characterized by a gradual loss of physiological functions, which leads to increased vulnerability of the organism to age-related diseases and, finally, to death. López-Otín et al. [1] proposed the original nine hallmarks of aging in an article published in Cell in 2013. Since then, the field of longevity medicine has experienced significant growth, with new research and studies enhancing our understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the aging process. In 2023, López-Otín et al. [2] published further research updating their previous work and adding three new hallmarks. Currently, the hallmarks of aging comprise genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient-sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, altered intercellular communication, dysregulation of RNA processing, microbiome disturbances, and chronic inflammation and, of interest for this review, compromised autophagy [1, 2].

The term Autophagy, derives from the Greek term “self-eating”, and represents an evolutionarily conserved catabolic process within eukaryotic cells. Its fundamental role resides in maintaining cellular homeostasis by selectively degrading and recycling damaged or obsolete intracellular components. There are three different autophagy pathways: macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) that assure healthy aging [3].

Macroautophagy involves the formation of double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes, which engulf cytoplasmic cargo. These autophagosomes subsequently fuse with lysosomes to form autolysosomes, where degradation occurs [4]. Autophagy-related proteins (ATGs) orchestrate this process, triggering autophagosome formation, trafficking, and fusion with lysosomes. Forkhead box O3 (FoxO3) activates transcription of autophagy genes such as LC3B, GABARAPL1 and Beclin-1 while Transcription factor EB (TFEB) enhances lysosomal biogenesis, amplifying macroautophagy by upregulating related genes. Key upstream regulators of macroautophagy are mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) pathway, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) pathway [5]. The protein mTOR is a master regulator of cellular metabolism and it is involved in the autophagic process both upstream and downstream. In a nutshell, the activation of mTOR (e.g., under nutrient abundance) leads to the inhibition of the autophagic process. The AMPK pathway is a signaling pathway closely linked to cellular metabolism that initiates a series of cellular processes aimed at increasing ATP levels. Through the inhibition of mTOR, the AMPK pathway regulates positively the autophagic process boosting autophagy [6].

This catabolic process requires the synchronization of different molecular events such as direct phosphorylation of serine/threonine-protein kinase (ULK1), regulatory-associated protein of mTOR (RAPTOR) and the tuberos sclerosis complex protein 1 and 2 (TSC1-TSC2) complex by mTOR and AMPK or the binding of Atg14 to the Beclin-1–VPS34 complex for autophagy initiation. Different transcription factors also modulate macroautophagy [7]. Interestingly, these regulatory systems are cellular signaling mechanisms that respond to various stressors and nutrients availability to either activate or inhibit autophagy. Since autophagy can maintain cellular homeostasis, and eliminar health, this process has drawn significant attention in the context of aging.

CMA is a selective protein degradation process that targets proteins carrying a specific targeting motif in their amino acid sequence (KFERQ). The cytosolic chaperone heat shock Cognate 70 (HSC70) recognizes this motif, transporting protein substrates to the lysosomal membrane where interacts with Lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2A), the CMA receptor, facilitating their internalization into lysosomes. Multimeric LAMP2A assists substrate translocation, aided by luminal HSC70 and stabilized by luminal heat shock protein 90 (HSP90). CMA contributes to quality control of oxidized proteins, provides amino acids during nutrient scarcity, and regulates functional proteins in various cellular processes [8]. Stressors like starvation, oxidative stress, genotoxic damage, and hypoxia stimulate CMA. Regulators of CMA include diverse signaling pathways such as mechanistic target of rapamycin C2 (mTORC2) and PH domain and leucine rich repeat protein phosphatase (PHLPP1) [9].

The third type of autophagy, microautophagy consists in the direct invagination of the lysosomal membrane or endosomal membrane to trap cytosolic content. The endosomal microautophagy (eMI) operates in late endosomes, mediating selective or bulk protein degradation, recognized by cytosolic HSC70. Contrary to CMA, eMI does not require the factor LAMP2A or substrate unfolding, involving endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery for cargo internalization and degradation [10]. HSC70-dependent eMI is not upregulated by starvation but responds to proteotoxicity from pathogenic proteins like tau [11].

Mitophagy is a specific type of autophagy in which damaged or depolarized mitochondria are degraded in the lysosomal compartments. The correct turnover of these organelles is essential to maintain cell homeostasis and to avoid cell degeneration. This evolutionarily conserved mechanism participates in physiological roles in the cell, such as cell maturation, differentiation, and remodeling [12]. In a nutshell, damaged mitochondria are tagged by specific markers such as PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and, then recognized by PARKIN. This effector ubiquitinates proteins from the outer mitochondrial membrane, leading to the recruitment of other proteins linked to autophagy. The autophagic machinery forms the autophagosome, and this structure is consequently fused to the lysosome [13]. The process of mitophagy is becoming more significant in pathological situations, such as age-related illnesses. The impairment of mitophagy is considered one of the several aging hallmarks. For instance, as we age the mitophagy efficiency often declines, leading to the accumulation of defective mitochondria. The dysfunction of mitophagy exacerbates also the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), a key event that occurs in aging. Defective mitophagy directly participates in the development and progression of several age-related pathologies, mostly including oxidative stress, as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, and cardiovascular diseases [14].

As previously said, autophagy declines with age progression, thus causing accumulations of defective organelles, proteins and macromolecules that in turn cause cellular stress and disfunction. Nevertheless, several studies shows in this section underline how enhanced autophagic activity positively affects cellular resilience and longevity and show that efficient autophagy maintains cellular health and promotes longevity [5]. Conversely, the age-related autophagy decline may predispose individuals to multiple aging-associated pathologies [15]. As well as, impaired autophagy has been linked to multiple diseases including neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and metabolic disorders [2, 4, 16]. Autophagy also plays a crucial role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis by regulating lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. Dysfunctional autophagy in metabolic tissues contributes to the onset and progression of metabolic diseases such diabetes and obesity. Research suggests that enhancing autophagy flux in metabolic tissues could hold promise in ameliorating metabolic disorders and delaying their associated aging phenotypes [17]. Also, autophagy plays a pivotal role in clearing toxic protein aggregates, thereby attenuating the progression of neurodegenerative disorders, which are present in many older people [15].

In sum, a better understanding of the role of autophagy in aging has open the doors for potential therapeutic interventions in age-related diseases. The identification of safe and effective activators to rejuvenate cellular function and mitigate the effects of aging and age-related diseases is a challenge. Although, various strategies including caloric restriction, nutritional components, exercise, and pharmacological approaches, have been shown promising in enhancing autophagy [18, 19], the interventions targeting directly autophagic process are limited nowadays. Thus, the use of autophagic activators in clinical context remains aspirational.

In recent years, researchers have made significant progress in understanding the molecular and cellular mechanisms involved in the aging process. This knowledge has led to the development of new interventions aimed at prolonging life expectancy and promoting healthy aging. Anti-aging processes can be regulated by behavioral, pharmacological, and dietary factors [20] and polyphenol-based nutritional interventions are one of the most studied measures to promote healthy aging.

Polyphenols are a group of secondary plant metabolites identified by their chemical structure of repeating phenolic moieties. Polyphenols are very abundant in nature and extremely diverse. There are more than 8000 different ones identified and are widely distributed into Plant kingdom, mainly in fruits and vegetables [21]. Due to that huge diversity, the terminology and classification of polyphenols is complex and confusing. Polyphenols have very similar chemical structures, although they can be subdivided based on some differences in five main groups eliminar, including: flavonoids, stilbenes, lignans phenolic acids and phenolic alcohols. Flavonoids are subsequently divided into flavanols, flavonols, flavones, flavanones, isoflavones and anthocyanidins [21].

Polyphenols can exert multiple biological effects such as: protect cellular components against oxidative damage, regulate enzymes activity, and acting in the interaction with signal transduction pathways and cellular receptors [22]. These bioactive molecules act as caloric restriction mimetics, extending lifespan and offering a similar anti-aging and protective action than the one that caloric restriction provides. Polyphenols play a potential anti-aging role in many ways, due to their ability to modulate some of the hallmarks of aging, including oxidative damage, inflammation, cell senescence, and autophagy [22]. Moreover, these metabolites are receiving increasing attention as potential therapeutic agents against various aging diseases such as cardiovascular and kidney diseases, diabetes, and even neurodegenerative diseases [23].

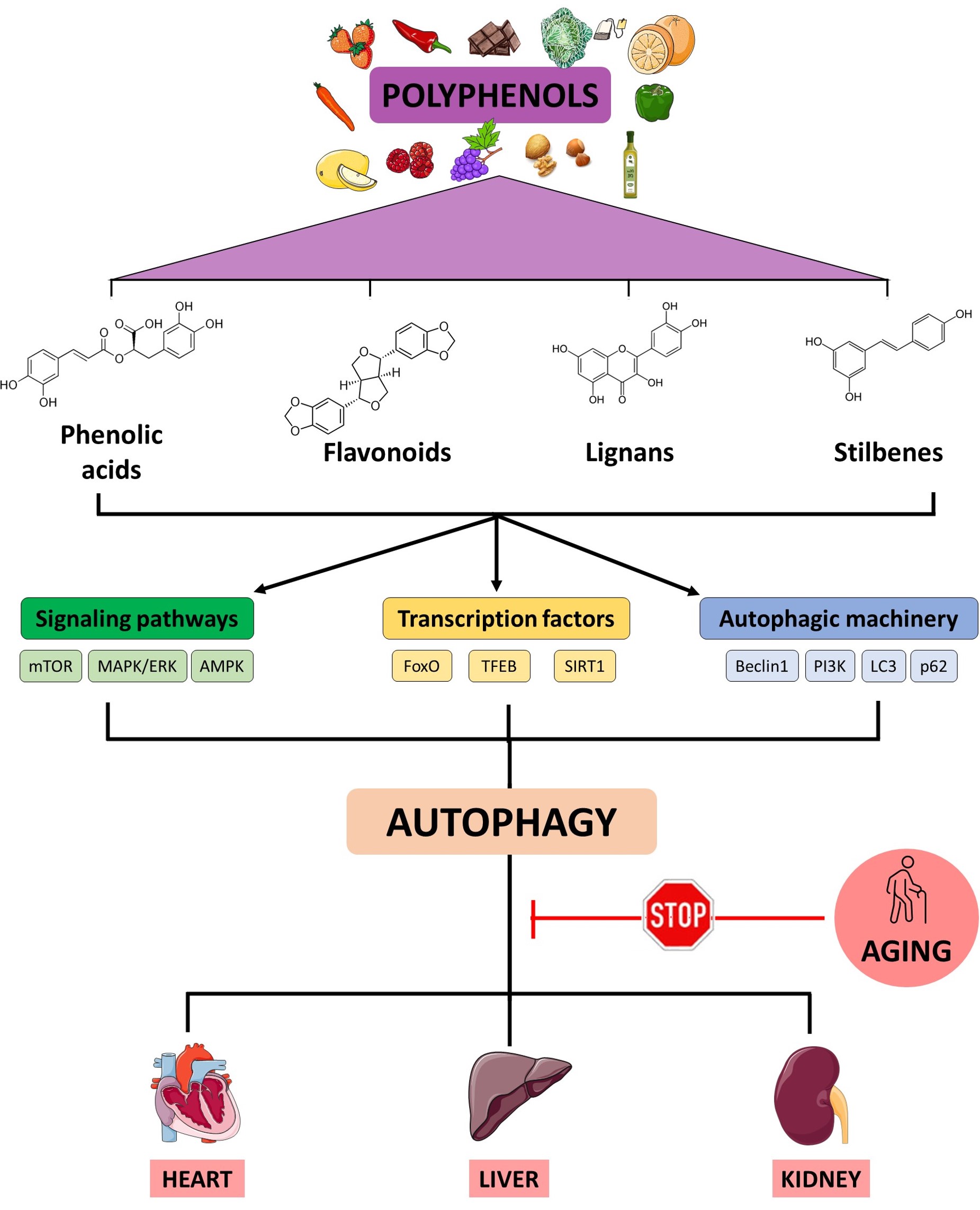

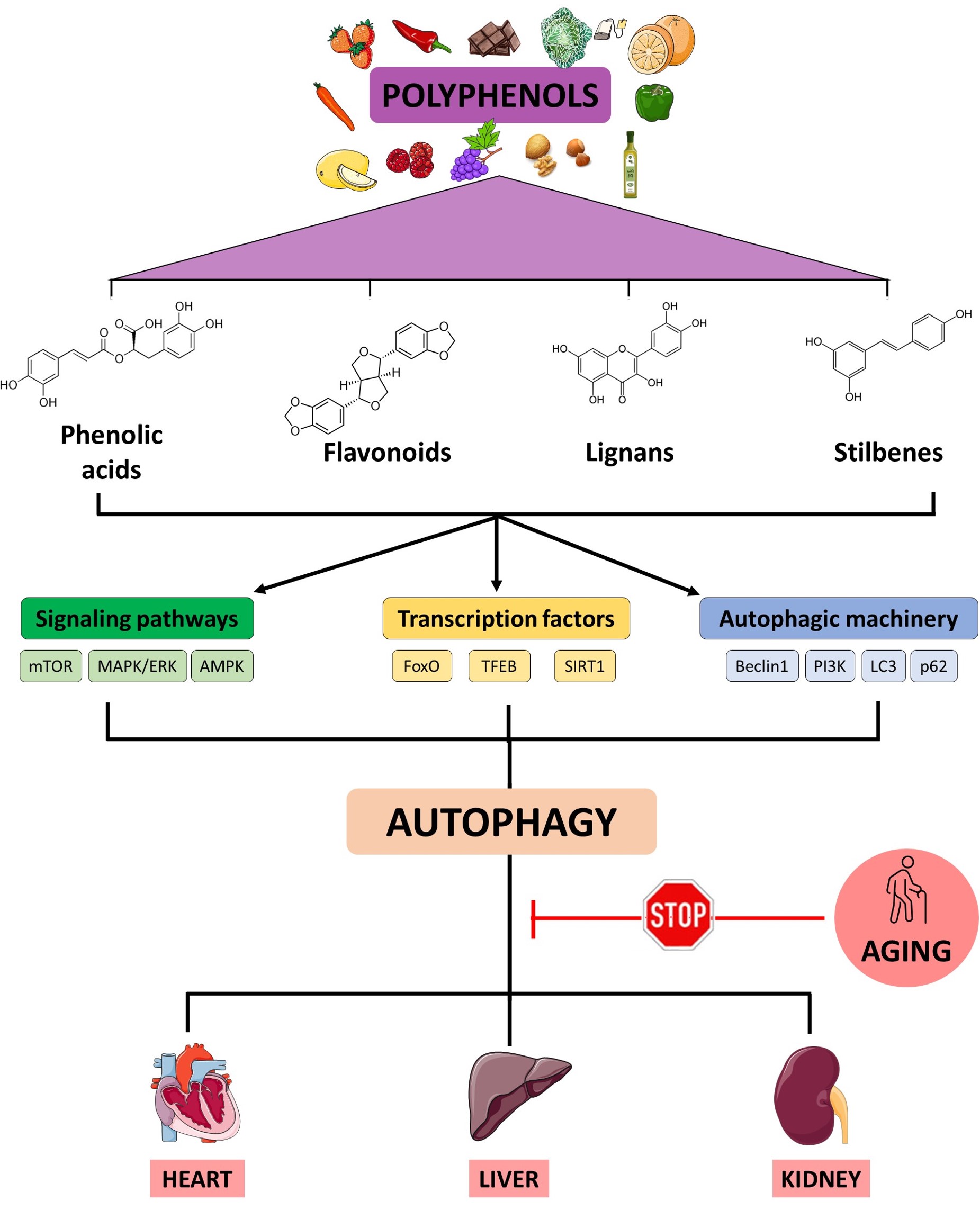

In the last decades, natural compounds such as spermidine, trehalose or polyphenols have gained attention as potential autophagic activators [24]. Some of these metabolites can modulate macroautophagy (Fig. 1), but it remains unknown if polyphenols specifically could modulate microautophagy or chaperone-mediated autophagy. Some polyphenols are activators of sirtuine 1 (SIRT1) that controls key autophagic genes such ATG5, ATG7 or LC3 [25]. A key outcome of activating SIRT1 through polyphenol exposure is the downregulation of the mTOR signaling pathway. This, in turn, initiates the process of autophagy through the protein complex containing ULK1/2 and two additional protein factors, autophagy related 13 (ATG13) and FIP200 (ULK1/2-ATG13-FIP200) [26]. Also, increasing evidence shows that polyphenol consumption activates autophagy through the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathways and contributes to delaying aging and maintaining health in various model organisms [27]. Of these regulators, the protein kinase B (AKT) and PI3K are the well-known upstream activators of mTOR1. For example, resveratrol in rats, kaempferol in human endothelial cells, gallic acid both in CCD-18Co cells and in rats were reported to up-regulate autophagy process via inhibiting PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [28, 29, 30].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Working model of the action of polyphenols on autophagy-related pathways. An age-related decline of autophagy is linked to pathophysiological processes described in heart, liver and kidney disorders. Polyphenols might enhance autophagy through the activation of different cellular factors involved in the autophagic function. mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; MAPK/ERK, mitogen-activated protein kinases/extracellular signal-regulated kinases; AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; FoxO, Forkhead box O3; TFEB, transcription factor EB; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; PI3K, phosphatidyl inositol 3 kinase; LC3, Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3. Created with Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Polyphenols contribute to mitochondrial health by activating mitophagy, a

subtype of macroautophagy, which helps remove damaged mitochondria and prevents

the accumulation of oxidative stress within cells, thereby promoting longevity

and preventing age-related pathologies associated with mitochondrial dysfunction

[31, 32]. In particular, resveratrol and epicatechin activate mitochondrial

biogenesis via Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator

1-alpha- sirtuin 1- AMP-activated protein kinase (PGC-1

In this review we summarize the current knowledge about the modulatory role of polyphenols in macroautophagy. Specifically, we will focus on the interconnectedness polyphenols-autophagy in the pathophysiology of three major organs whose diseases represent a major cost to the healthcare system. The use of polyphenols might represent a choice for cost-effectiveness and efficiency strategy to counteract cellular damage in tissues and organs with age.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the world’s largest cause of mortality, claiming 17.9 million lives annually, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Given that aging brings both structural and functional changes to the cardiovascular system, it is one of the major risk factors for CVDs. With age, there is an increase in arterial stiffness, an impairment in endothelial function, and many other physiological changes such as heart hypertrophy, fibrosis, ischemia, and increased incidence of atherosclerosis, among others [34]. In recent years, the interplay between the modulation of autophagy and cardiovascular system fitness has been studied as a remarkable therapeutic axis [35]. In CVDs, autophagy acts as a double-edged sword. In general terms, autophagy, at physiological levels, is beneficial to maintain the correct functioning of cardiovascular-associated tissues and the enhancement of autophagic activity is cardioprotective in multiple pathological conditions [36]. However, the aberrant activation of autophagy can cause cell death and accelerate the disease progression during specific stages of the pathology [37].

A fine-tuning modulation of the autophagy is key to designing effective autophagy-related therapeutic strategies. In this context, polyphenols are being studied due to their multiple benefits to the cardiovascular system (Table 1, Ref. [29, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70]). Apart from their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, polyphenols have been demonstrated to be a powerful tool in modulating autophagy both in cardiovascular health and disease [71].

| Family | Polyphenol | Dose | Model of the study | Disease | Signaling pathway | Reference |

| Flavonoid | EGCG | 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg | Rat | Diabetes | AMPK/mTOR | [38] |

| 10 mg/kg | Rat | Ischemia-reperfusion | PI3K/AKT | [39] | ||

| 1, 5, 10 µmol/L | HUVECs | Oxidative stress-derived damage | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | [40] | ||

| 10 µM | BAOEC | Lipid accumulation | Ca2+/CaMKK |

[41] | ||

| Quercetin | 10 mg/kg | Rat | Hypertension | - | [42] | |

| 12.5 mg/kg | Rat | Cholesterol accumulation | mTOR | [43] | ||

| 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 mg/L | Human cardiomyocytes | Hypoxia-reoxygenation | SIRT1 | [44] | ||

| Rutin | 12.5 µg/mL | Macrophages | Atherosclerosis | PI3K/AKT | [45] | |

| 100 mg/kg | Mice | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity | Akt | [46] | ||

| Kaempferol | 100 mM | HUVECs | Atherosclerosis | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | [29] | |

| 1000 nM | HUVECs | Atherosclerosis | SIRT1/LKB1/AMPK | [47] | ||

| Apigenin | 50 mg/kg | Mice | Myocardial damage | TFEB | [48] | |

| Luteolin | 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg | Mice | Diabetic cardiomyopathy | JNK/c-Jun-regulated miR-221-associated pathway | [49] | |

| 10 µg/kg | Mice | Myocardial injury | AMPK | [50] | ||

| 10 µg/kg | Mice | Myocardial injury | - | [51] | ||

| 8 µmol/L | Cardiomyocytes | Hypoxia | ||||

| 25 µM | RAW264.7 macrophages | Atherosclerosis | - | [52] | ||

| 10 µM | Adult mouse cardiomyocytes | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity | TFEB | [53] | ||

| Baicalein | 25 mg/kg | Mice | Cardiac hypertrophy | FOXO3a | [54] | |

| 30 µM | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | |||||

| Naringenin | 5, 10, 20 and 40 µmol/L | H9C2 cardiomyocytes | Myocardial injury by hypoxia | HIF-1 |

[55] | |

| 1 and 10 µM | HUVECs | Palmitate-derived cardiotoxicity | JNK | [56] | ||

| 86 µM | HUVECs | High glucose/high-fat stress | PI3K-AKT-mTOR | [57] | ||

| 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg | Mice | Atherosclerosis | - | [58] | ||

| Stilbenes | Resveratrol | 20 µM | H9C2 cardiomyocytes | Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity | AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 | [59] |

| 2.5 mg/kg/day | Rats | Myocardial ischemia-derived injury | - | [60] | ||

| 0.1 and 1 µM | H9C2 cardiomyocytes | Hypoxia-reoxygenation | mTORC2 | |||

| 25 µM | H9C2 cardiomyocytes | Diabetic cardiomyopathy | mTORC1/p70S6K1/4EBP1 | [61] | ||

| 5 and 20 µM | Primary neonatal rat cardiomyocyte | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | Sirt1/Sirt3-FoxO | [62] | ||

| 30 mg/kg | Rats | Ischemia-reperfusion injury | DJ-1/MEKK1/ | [63] | ||

| 20 µM | H9c2 cardiomyocytes | JNK | ||||

| 8 mg/kg | Rats | Heart failure | AMPK | [64] | ||

| Phenolic acids | Gallic acid | 5 and 20 mg/kg | Mice | Cardiac hypertrophy | ULK1 | [65] |

| 10 µM | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | |||||

| Other polyphenols | Curcumin | 20 µmol/L | Macrophages | Atherosclerosis | mTOR-TFEB | [66] |

| 5 and 20 µmol/L | EA.hy926 cells | Oxidative stress | AKR-mTOR | [67] | ||

| 1, 5 and 10 µmol/L | HUVECs | Oxidative stress | FOXO-1 | [68] | ||

| 20 µmol/L | Mouse aortic smooth muscle cell line (MOVAS) | Atherosclerosis | ERS | [69] | ||

| Rat thoracic aorta cell line (A7r5) | ||||||

| 10 µM | H9C2 cardiomyocytes | Hypoxia-reoxygenation | BNIP3 or SIRT1 | [70] |

ECGG, epigallocatechin gallate; HUVECs, human umbilical vein endothelial cells;

BAOEC, bovine aortic endothelial cells; AMPK/mTOR, AMP-activated protein kinase/Mechanistic target of rapamycin; PI3K/AKT, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B; CaMKK

One of the most studied polyphenols in autophagy modulation is

epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) a flavonoid, formed by the combination of

epigallocatechin and gallic acid. EGCG belongs to the catechin family, with a

flavanol structure, and is abundant in green tea, with significant levels also

found in white tea and smaller quantities in black tea [72]. Several in

vivo and in vitro studies strengthen the autophagic-mediated

cardioprotective capacity of this bioactive compound [73]. In type 2 diabetic

rats, the intragastrical administration of 40 mg/kg and 80 mg/kg of EGCG

increased the expression of myocardial LC3 and Beclin-1. Since levels of AMPK-p

are increased and levels of mTOR are decreased, the authors suggest that the

autophagic modulation could be exerted through the AMPK/mTOR pathway and entails

lower deposition of collagen fibers, less inflammation, and hypertrophy in the

myocardium, and ameliorated several clinical parameters related to cardiac in

EGCG-treated animals [38]. Administration of EGCG 10 mg/kg via sublingual

intravenous injection in a rat model of ischemia/reperfusion injury, reduced

cardiomyocyte apoptosis, restored the levels of critical myocardial enzymes, and

curtailed the infarct area [39]. The authors showed that EGCG treatment targets

PI3K/AKT downstream autophagic effectors such as Beclin-1, Atg5, p62, and LC3-II.

Xuan and Jian [39] suggest that these effects can be explained by the

EGCG-mediated abrogation of the detrimental excessive autophagic flux. The

PI3K/AKT pathway seems to play a major role in EGCG-mediated modulation of

autophagy in CVDs. In an in vitro model of oxidative stress-induced

damage in Primary Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells (HUVECs), EGCG reduced

cell apoptosis, enhanced cell survival, and upregulated Atg5, Atg7, LC3 II/I, and

the Atg5-Atg12 complex through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway [40].

Interestingly, EGCG has been also tested in the reduction of the endothelial

accumulation of lipid droplets, a hallmark of atherosclerosis. The

palmitate-derived accumulation of lipids bovine aortic endothelial cells was

reduced by 10 µM EGCG treatment. The authors demonstrated that heightened

intracellular calcium dynamics activating CaMKK

Quercetin, a natural flavonol broadly used in traditional chinese medicine, is found in various fruits, vegetables, and grains of human diet. This polyphenol has also been extensively investigated in the context of cardiovascular diseases, due to its therapeutic potential. Lin et al. [42] noticed that this polyphenol could promote autophagy in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Animals administered orally quercetin (10 mg/kg body weight) once per day for 6 weeks had a reduction in blood pressure and an enhancement of vascular endothelial function. The protective role of quercetin treatment in atherosclerosis has been also confirmed in ApoE-/- mice subjected to a high-fat diet, the treatment with a daily oral gavage of a quercetin solution (12.5 mg/kg) for 12 weeks resulted in the reduction of lipid accumulation in the aorta. Transmission electron microscopy analysis of the aortic tissue of quercetin-treated animals showed an increased number of autophagosomes. Western Blot analysis showed reduced levels of mTOR, p53, and p21 proteins, as well as an increase in the Microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3-II/I (LC3II/I) ratio as compared to the control group [43]. Also, in cardiomyocytes subjected to hypoxia/reoxygenation, quercetin acts as a potent antioxidant inhibiting the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and as a mitochondria quality agent by the modulation of mitophagy. Remarkably, the protective effect of quercetin in cardiomyocytes is offset by the silencing of SIRT1, a key effector in cell metabolism, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function [44].

Rutin, found in various plants including citrus, is a flavonoid glycoside that combines the flavonol quercetin with the disaccharide rutinose and it has been proposed as an interesting anti-inflammatory and anti-atherosclerotic agent. The application of 12.5 µg/mL of rutin to a macrophage-derived foam cell model inhibits the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and increases the LC3II/LC3I ratio and the number of autophagosomes in macrophages. Therefore, rutin decreases macrophage inflammation and the production of foam cells induced by elevated levels of oxygenated low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) levels [45]. In a mouse model of doxorubicin-induced toxicity, administration of rutin 100 mg/kg body weight for 11 weeks improved the cardiac function, attenuated cardiac fibrosis and apoptosis, and reduced LC3-II and Autophagy-related 5 (ATG5) expression. In the same study, the authors demonstrated that the AKT pathway mediated this decrease through “excessive” autophagy [46].

The flavonol kaempferol has shown antiatherosclerosis activity by modulating both inflammation and autophagy. Kaempferol is a bioactive flavonoid isolated from black, green, and mate herb teas as well as from numerous common vegetables and fruits, including beans, grapes, broccoli, berries, kale, citrus fruits, and from plants or botanical products and is commonly used in traditional medicine [74]. In an ox-low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-induced apoptosis model the treatment with 100 mM kaempferol ameliorated the apoptotic rate and boosted autophagy in HUVECs by up-regulation of autophagy via inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in human endothelial cells [29]. Using the same cellular model, 1000 nM of genistein, induced SIRT1/LKB1/AMPK-dependent autophagy with increased LC3-II, and decreased p62. In this case, autophagic flux was associated with genistein-induced inhibition of mTOR pathway and SIRT1/LKB1/AMPK pathway was also involved, mitigating senescence in ox-LDL-injured HUVECs [47].

Apigenin, a from the flavone family that is mainly found in parsley, artichokes, and spinach, has shown autophagy-related promising cardioprotective properties. In a mouse lipopolysaccharide-induced myocardial toxicity model, the intraperitoneal administration with 50 mg/kg of body weight resulted in enhanced cardiomyocyte cell survival, the attenuation of oxidative stress, and the reduction in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Li et al. [48] found that the treatment with apigenin also modulated the autophagic process through TFEB, a master transcriptional regulator involved in the regulation of the expression of genes related to cellular clearance processes such as autophagy. In the group treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and apigenin, the levels of ATG5 and Lysosome-Associated Membrane Protein 1 (LAMP1) were increased, while p62 expression was reduced [48]. Interestingly, growing literature highlights that apigenin can modulate various microRNAs (miRNAs), involved in different steps of the pathophysiology of CVDs and it could be linked to autophagy modulation [75, 76]. For instance, the modulation of miR-103-1-5p by apigenin has been linked to influence in PARKIN-mediated mitophagy in an in vitro acute myocardial infarction model [77].

Another compound from the flavone family that has been tested for its potential in autophagy modulation in CVDs is luteolin the lutein. This flavonoid has shown powerful in vivo autophagy-mediated cardioprotective properties. In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, the treatment with luteolin 50, 100 and 200 mg/kg for 4 weeks attenuated cardiac fibrosis and diabetic cardiopathy hallmarks. The authors suggest that this protection is partially mediated by the enhancement of autophagy by the suppression of the N-terminal Kinase (JNK)/c-Jun-regulated miR-221-associated pathway [49]. Intraperitoneal injection of luteolin (10 µg/kg) improved cardiac function, decreased apoptosis, and protected against oxidative stress and inflammation in a mice model of sepsis-induced myocardial injury. The cardioprotective effect was abrogated when using 3-methyladenine, an autophagy inhibitor, and dorsomorphin, an AMPK inhibitor, suggesting that luteolin modulates AMPK-dependent autophagy [50]. The same dose of luteolin reduced apoptosis, cardiac dysfunction, and the inflammatory response in a post-myocardial infarction mouse model. Interestingly, by using a mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) knockout mouse, the authors demonstrated that the cardioprotection is mediated by this effector. In the same study, the authors reported that the administration of luteolin 8µmol/l to cardiomyocytes that underwent hypoxia resulted in the restorement of the mitochondrial function and increased the autophagic flux by Mst1 suppression [51]. Mst1 has been proved to inhibit autophagy by facilitating the interplay between Bcl-2 and Beclin1 [78]. Mounting in vitro evidence also supports the promising potential of luteolin as a therapy in CVDs. The treatment with 25 µM luteolin to murine RAW264.7 foam macrophages led to ox-LDL decreased foam cell formation and cell apoptosis. This protection is mediated by the autophagic process since the protective effects offered by luteolin were suppressed when 3-MA was used to inhibit autophagy [52]. In addition, 10 µM luteolin stimulates TFEB-mediated mitochondrial autophagy in adult mouse cardiomyocytes subjected to doxorubicin-induced toxicity [53].

Another natural flavonoid used in traditional chinese medicine such as baicalein

or naringenin have multiple properties regarding the cardiovascular system.

Baicalein, extracted from the root of Scutellaria baicalensis, lowered

the production of ROS and stimulated FUN14 Domain Containing 1 (FUNDC1)-mediated

mitophagy in an in vitro and in vivo model or cardiac

hypertrophy [54]. Measurement of LC3-I, LC3-II and p62 levels and monitoring of

autophagosome formation by confocal microscopy using monomeric red fluorescent

protein- green fluorescent protein mRFP-GFP tandem fluorescently tagged LC3

showed that baicalein promotes autophagic activity [54]. Naringenin, a natural

flavonoid commonly found in citrus fruits, belongs to the flavanone family, has

been shown to impact multiple signaling pathways, particularly in the context of

myocardial ischemia [79]. In H9C2 cardiomyocytes treated with cobalt chloride

(CoCl2), an in vitro model of myocardial injury by hypoxia, cells

pretreated with different concentrations of naringenin exhibited enhanced cell

survival, and reduced cell apoptosis. Naringerin bypassed the CoCl2-derived

blockade of autophagy (measured as a Western Blot quantitative analysis of

Beclin-1 expression, p62 expression, and LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio) by promoting the

activation of the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 Alpha/ Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa

Interacting Protein 3 HIF-1

Stilbenes are being investigated for their potential to modulate autophagy in cardiovascular disorders, being the resveratrol is probably the most studied polyphenol of this family. Resveratrol is found in some fruits such as grapes, blueberries, blackberries, and peanuts. Gu et al. [59] shown that 20 µM resveratrol treatment in a doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in vitro model stimulated autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway and also in vivo reduced apoptosis in the cardiac tissue of rats. The autophagic process was boosted in the myocardium in rats fed with resveratrol 2.5 mg/kg/day, and this event correlated negatively with the apoptosis of cells from the left ventricular tissue. Also, low doses of resveratrol (0.1 and 1 µM) increased autophagy and enhanced cell survival in H9C2 cardiomyocytes subjected to 30 minutes of hypoxia followed by reoxygenation. The authors claimed that the cardioprotective effects of resveratrol treatment were mediated by the rapamycin-insensitive companion of mTOR (RICTOR)-mediated mTORC2 pathway [60]. These results are in line with other study that analyzed the effects of resveratrol in an in vitro model of diabetic cardiomyopathy where 25 µM resveratrol restored the palmitate and high glucose-derived decline of autophagy in H9C2 cells [61]. Interestingly, resveratrol has also been linked to improve mitochondrial quality control in CVDs. In an in vitro model of ischemia/reperfusion injury, 5–20 µM increased the content of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP), Nucleotide Monophosphate (NMP), SOD activity in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte primary cultures and stimulated mitophagy, an event that seems to be mediated by the activation of the SIRT1/SIRT3-FoxO signaling pathway [62]. However, recent literature suggests that resveratrol might decrease autophagy in certain pathological contexts where the excess of autophagic activity is detrimental. Resveratrol has been proven to decrease autophagy through the DJ-1 (PARK7)/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase 1/c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (DJ-1/MEKK1/JNK) pathway in an in vitro model ischemia-reperfusion injury [63]. In addition, the administration of resveratrol (8 mg/kg/d by intraperitoneal injection) decreased the expression of autophagic markers and autophagic vacuoles in vivo [64].

Phenolic acids are a large family of secondary metabolites containing a phenolic ring and a carboxylic acid (C6-C1 skeleton). They can be divided into two classes: benzoic acid derivatives and cinnamic acid derivatives. Its main function is related to the color and sensory characteristics (flavor, astringency, hardness) of plants, as well as the antioxidant properties of foods of plant origin (fruits, vegetables, grains, tea, spices) and have emerged as promising autophagy modulators [80]. The only phenolic acid reported to be able to modulate autophagy in a CVD context is gallic acid. Gallic acid blocked hypertrophy-related signaling cascades and boosted autophagy in primary cardiomyocytes subjected to angiotensin II-derived hypertrophy [65]. In the same study was shown that the model ULK1-dependent autophagy is activated and autophagic inhibitors abrogated the protection, suggesting that the therapeutic effect is due to the autophagic process [65].

Finally, curcumin, extracted from turmeric curry spice, has been extensively

studied in inflammatory and oxidative stress-related conditions, including CVDs

[81]. 20 µmol/L of curcumin resulted in autophagic-mediated regulation of

the expression of inflammatory genes in macrophages exposed to ox-LDL, an

in vitro model of atherosclerosis. Li et al. [66] reported

enhancement in the autophagic flux dependent of the mTOR-TFEB axis. In EA.hy926

cells, a hybrid cell line that possesses hallmarks of vascular endothelial cells,

the pretreatment with 5–20 µmol/L curcumin diminished apoptosis and

increased cell viability in an H2O2-derived oxidative stress model. In

the same study, the authors describe that curcumin activated an adaptative

autophagic process by suppressing the phosphorylation of AKT and mTOR [67].

Curcumin was reported to activate Beclin-1 through and FOXO-1-induced autophagy

in oxidative stress model in human endothelial cells [68]. FOXO-1 is a

transcripction factor involved in several metabolic processes (e.g.,

gluconeogenesis) but that can also modulate the autophagic process.

Interestingly, curcumin has been tested as an autophagic modulator agent within

cutting-edge therapeutic approaches. A photodynamic laser therapy applied to

mouse aortic smooth muscle cell line and rat thoracic aorta cell line (A7r5)

treated with ox-LDL ameliorated the phenotypic changes associated with

atherosclerosis—foaming, cell migration, and production of ROS—by promoting

the autophagic activity [69]. The delivery of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles to

palmitate-treated cardiomyocytes—a lipotoxicity model—stimulated cell

survival, ameliorated palmitate-derived apoptosis, and activated autophagy. In

this case, the activation of adaptative autophagy is mediated by the endoplasmic

reticulum stress (ERS) pathway since the autophagic process can be abrogated

using salubrinal, an eIF2

Hepatic diseases comprise a wide range of disorders that affect the liver functionality. Their chronic occurrence represents an important burden to the healthcare system, being responsible for 1 out of every 25 deaths worldwide every year [82]. Cirrhosis, the scarring of the liver tissue, is one of the principal outcomes of many liver diseases and represents one of the major causes of liver disease-related deaths. Aging is one of the most important risk factors for developing both acute and chronic liver diseases such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [83]. The aging-related molecular and cellular changes affect dramatically liver cell function, including changes in cellular volume, cellular senescence, mitochondrial dysfunction, polyploidy and accumulation of dense bodies [84]. Autophagy plays a significant role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and energy regulation in hepatic cells and aging-related decrease in the autophagic capacity underlies liver dysfunction [85]. In particular, autophagy in the liver is considered highly important in lipid metabolism and detoxification [86]. Growing evidence suggests that many flavonoids can influence autophagic processes in liver cells, offering a potential avenue for therapeutic interventions in liver diseases (Table 2, Ref. [87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118]). In this section of the review, the capacity of polyphenols to modulate the autophagic process will be analyzed and how this influences the progression of liver-related diseases will be examined.

| Family | Polyphenol | Dose | Model of the study | Disease | Signaling pathway | Reference |

| Flavonoid | EGCG | 40 µM | HepG2 | Lipid accumulation | AMPK | [87] |

| 25 mg/kg | Huh7 cells | |||||

| Mice | ||||||

| 50 µM | Human liver cell lines L02 and QSG-7701 | NAFLD | ROS/MAPK | [88] | ||

| 25 and 50 µM | HepG2 cells | Hepatocellular carcinoma | - | [89] | ||

| 10 and 30 mg/kg | Mice | Acute autoimmune hepatitis | BNIP3 | [90] | ||

| Quercetin | 100 mg/kg | Mice | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease | mTOR | [91] | |

| 100 mg/kg | Mice | Ethanol-induced liver injury | FOXO3/AMPK-ERK2 | [92] | ||

| 80 mg/kg | Mice | NAFLD | AMPK | [93] | ||

| 50 µM | HepG2 cells | Rab7 | ||||

| 100 and 200 mg/kg | Mice | Liver cirrhosis | TGF- |

[94] | ||

| Kaempferol | 5 mg/kg | Mice | ALF | MAPK | [95] | |

| 0.01 and 10 µM | Primary hepatocytes | |||||

| 10 and 20 µM | HepG2, THP‐1, and Caco2 cells | Triglyceride accumulation | Akt-mTOR | [96] | ||

| Baicalein | 100 mg/kg | Rats | Ischemia/reperfusion injury | HO-1 | [97] | |

| 50, 100 and 200 µmol/L | Human liver LO2 cells | Hypoxia/reoxygenation | - | [98] | ||

| 100 mg/kg | Rats | CCl4-induced hepatic damage | - | [99] | ||

| Naringenin | 100 mg/kg | Mouse | ALF | AMPK | [100] | |

| Rutin | 0.2 mg/mL | Mice | Aging | - | [101] | |

| HepG2 cells | ||||||

| 200 mg/kg | Mice | NAFLD | - | [102] | ||

| 10–40 µM | HepG2 cells | |||||

| 50 and 100 mg/kg | Rats | Pharmacological liver damage | - | [103] | ||

| Apigenin | 20 µM | Huh7 cells | Hepatic lipid accumulation | - | [104] | |

| HepG2 cells | ||||||

| Murine hepatocyte cell line AML12 | ||||||

| 10 µg/mL | HepG2 cells | Oxidative stress | NQO2/AMPK | [105] | ||

| 20 and 40 mg/kg | Mice | Liver fibrosis | TGF- |

[106] | ||

| Stilbenes | Resveratrol | 40, 120 and 200 mg/kg | Rats | Liver fibrosis | PTEN/PI3K/AKT | [107] |

| 10, 30 and 50 mg/mL | HSC-T6 cells | |||||

| 10, 30 and 100 mg/kg | Mice | AFL | - | [108] | ||

| 45 µmol | HepG2 cells | |||||

| 50 mg/kg | Mice | NAFLD | ULK1 | [109] | ||

| 0,1, 1, 10, 50 and 100 µM | JS1 cell line | Hepatic stellate cell activation | SIRT1 and JNK | [110] | ||

| - | HepG2 cells | NAFLD | cAMP/AMPK/SIRT1 | [111] | ||

| 200 mg/kg | Rats | NAFLD | - | [112] | ||

| Pterostilbene | 20 mg/kg | Mice | Alcoholic liver disease | - | [113] | |

| 5, 10 and 20 µM | LO2 cells | |||||

| - | Mice | NAFLD | AMPK/mTOR | [114] | ||

| 12.5 and 25 µM | HepG2 cells | |||||

| Phenolic acids | Rosmarinic acid | 20 µM | HepG2 cells | Lipid accumulation | - | [115] |

| Ferrulic acid | 25, 50 and 100 µM | AML-12 hepatocytes | Lipid accumulation | SIRT1 | [116] | |

| 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg | Mice | Pharmacological liver damage | AMPK | [117] | ||

| Mouse primary hepatocytes | ||||||

| Other Polyphenols | Curcumin | 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg | Rats | Liver fibrosis | AMPK/PI3K/ | [118] |

| AKT/mTOR |

EGCG, epigallocatechin gallate; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease;

AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; ROS/MAPK, reactive oxygen species/mitogen-activated

protein kinase;

BNIP3, Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting protein 3; mTOR, mechanistic target of rapamycin; FOXO3/AMPK-ERK2, forkhead box O3/AMP-activated

protein kinase - extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2;

TGF-

EGCG plays a key role in the autophagy-mediated elimination of lipids in hepatic

diseases in a dose-dependent manner. Different assays confirmed that 40

µM of EGCG boosts autophagy in in vitro models of hepatic

diseases and is associated to lipid clearance in cells [87]. 50 µM EGCG for

24 h promoted cell growth, decreased apoptosis, and stimulated autophagy in human

liver cell lines [88]. EGCG can avoid the release of

Quercetin is another flavonoid extensively studied in the context of hepatic

diseases. The modulation of autophagy via quercetin treatment has been reported

to have a direct positive impact in in vivo and in vitro

hepatic models. The long-term administration of quercetin in animal models of

hepatic diseases is effective in the modulation of the protein levels of several

autophagic markers, such as p62, mTOR, and LC3-II [91]. Quercetin can bypass the

chronic ethanol-induced hepatic mitophagy suppression [92]. In another study

[93], the treatment with quercetin (80 mg/kg/day) for 4 weeks in a mouse model of

NAFLD ameliorated the liver histological changes of the disease, decreased the

lipid accumulation in the liver, reduced ROS levels, and exerted

anti-inflammatory effects at TNF-

Different studies point out that kaempferol influence autophagy through a variety of mechanisms, and the dosage may play a significant role in the design of the therapy. For instance, in a mouse model of acute liver failure (ALF), 5 mg/kg kaempferol stimulated autophagy and offered hepatoprotection, and the pharmacologic blockade of autophagy abrogated the therapeutic effects of kaempferol in the animals. In the same study, the authors demonstrated that high doses (10 µM) of kaempferol in primary hepatocytes can inhibit the autophagy process, while low doses (0.01 µM) stimulate the autophagic capacity [95]. Kaempferol has also shown effectiveness against heavy metals-induced toxicity in the liver. Kim et al. [119] observed that the reversion of ferroptosis might be mediated, at least in part, by the kaempferol-mediated enhancement of autophagy, and that this modulation occurs via mTOR and ULK1. This polyphenol has also been linked to contributing to autophagy-mediated triglyceride clearance in the liver through the AKT-mTOR pathway [96].

Baicalein has been demonstrated to modulate autophagy in several hepatic diseases from a therapeutic point of view. Baicalein 100 mg/kg stimulated autophagy in a rat model of liver ischemia/reperfusion injury based on LC3-II data [98]. Interestingly, the use of 3-methyladenine worsened the pathological hallmarks of the disease. By using an inhibitor of Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), the authors demonstrated that the autophagic modulation exerted by baicalein is mediated, at least partially, by HO-1 [98]. Baicalein also seems to be effective in counteracting liver hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. 50–200 µmol/L baicalein stimulated autophagy and cell survival in a normal human liver LO2 cell model of hypoxia/reoxygenation alleviating endoplasmatic reticulum stress (ER) stress and apoptosis [98]. In CCl4-induced hepatic damage rats, baicalein elevated the protein levels of Atg5, LC3-II, and Beclin-1 and increased the number of autophagosomes in hepatocytes [99]. Nonetheless, the article lacks clarity regarding the precise correlation between the rise in autophagic activity and hepatoprotection.

Compelling literature suggests the key role of naringenin in both in vivo and in vitro models of hepatic diseases. Using robust methods such as the mCherry-GFP-LC3 reporter to monitor the autophagic flux, it was confirmed that naringenin can bypass the autophagic blockade present in steatotic hepatocytes leading to reduction of lipids in palmitic acid-treated hepatocytes [120]. In a lipopolysaccharide/D-galactosamine-induced acute liver failure mouse model, the intraperitoneal administration of naringenin 100 mg/kg diminished the histopathological hallmarks of the disease in an autophagic dependent-manner Interestingly, it was proved that naringenin can bind and modulate the regulatory gamma1 subunit of AMPK that might modulate autophagic function and event that can be crucial in autophagy regulation terms [100]. The results about the modulation of some polyphenols are controversial or there is limited information about the interaction with the autophagic process. Examples of these polyphenols could be rutin or apigenin. In an aging mice model, 0.2 mg/mL sodium rutin in drinking water increased lifespan, reduced liver steatosis, and altered the gene metabolic profile of the animals. The authors injected the mice with AAV-RFP-GFP-LC3 expression plasmid to demonstrate the increase of autophagic flux in vivo [101]. However, rutin was also reported as a therapeutic agent in NAFLD by inhibiting the autophagic activity and, thus, lessening the release of free fatty acids in HepG2 cells [102]. Rutin has also shown protective activity in vivo against sodium valproate-derived toxicity, a compound used in the treatment of many psychiatric disorders. 50 or 100 mg/kg rutin showed many beneficial effects in valproate-administered rats such as the attenuation of oxidative stress, ER stress, and inflammation, and approached the levels of Beclin-1 to the control group after rutin treatment [103].

Apigenin is also being studied for its capacity to modulate autophagy through multiple mechanisms and have a positive impact on hepatic models. Apigenin can upregulate the expression of different autophagic-related proteins such as Beclin1, ATG5, ATG7 and LC3II, and this upregulation of the autophagic process is directly related to the elimination of intracellular fatty acids [104]. Interestingly, it has been proved that apigenin can activate autophagy in liver cells through the Nicotinamide Riboside Hydride-quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2), a key player in oxidative stress [105]. Pyroptosis, a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death, can be mitigated by the therapeutic effects of apigenin. This polyphenol can activate autophagy in palmitic acid-induced NOD-Like Receptor Protein 3 (NLRP3) pyroptosis in HepG2 cells, and the use of chloroquine reduced the protective effect of autophagy against this type of stress [106]. However, other study reported that apigenin-mediated downregulation of autophagy was linked to protection in an in vivo liver fibrosis model [121].

Hesperidin and luteolin, two flavonoids exhibit hepatoprotection by blocking autophagy and increasing autophagic flux, respectively [122, 123]. Nevertheless, there is little evidence available about their ability to regulate autophagy in the development of therapeutic strategies in a hepatic context.

Probably, the most investigated polyphenol in autophagy regulation is resveratrol. A wide variety of in vivo study in murine models support the potential of resveratrol as a promising autophagic-mediated therapeutic agent. In a CCL4-liver fibrosis-induced rat model different doses of resveratrol (40–200 mg/kg) protected against liver injury and increased Beclin-1 and ATG7 expression and decreased LC3-II/LC3-I ratio. By using an in vitro model of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-BB-stimulated HSC-T6 cells, Zhu et al. [107] demonstrate that resveratrol downregulated miR-20a activating PTEN/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Resveratrol also can ameliorate several pathogenic hallmarks associated with Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (AFLD) and Non- Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Tang et al. [108] showed that the administration of 30–100 mg/kg resveratrol by gavage to ethanol-induced alcoholic fatty liver rats ameliorated hepatic steatosis. In addition, resveratrol stimulated the autophagic-mediated elimination of triglyceride droplets in HepG2 cells grown in a media supplemented with 100 µM oleic acid and 87 mM alcohol [108]. Resveratrol attenuated the histological changes of NAFLD, improved glucose metabolism and diminished insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and inflammation in NAFLD mice. By using a ULK1+/- mice strain, the authors demonstrated how partial inhibition of ULK1 expression abrogated the protective effects of resveratrol [109].

Interestingly, resveratrol has demonstrated effectiveness in the modulation of SIRT1-dependent autophagy in combinatorial therapeutic strategies. Resveratrol as a single therapeutic agent has also been linked to the modulation of SIRT1-mediated autophagy. Zhang et al. [110] showed that resveratrol, in a dose-dependent manner, can inhibit the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSC), an event that has a significant role in liver fibrosis. The use of different inhibitors showed that the activation of autophagy exerts protective properties in the mouse HSC line JS1 and that this activation is mediated by SIRT1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways [110]. The combination of resveratrol and metformin has been shown to stimulate SIRT1-dependent in palmitic acid-induced HepG2 cells [111]. Combinatorial use of 200 mg/kg resveratrol (200 mg/kg bw) and caloric retriction decreased the accumulation of intracellular lipid droplets in hepatocytes and parameters related to endoplasmic reticulum stress in high-fat diet rats. Although mRNA levels of several autophagic markers such as Beclin-1, LC3 and p62 suggest autophagy activation, further experiments are needed to demonstrate the association between SIRT1, autophagy, and the protective effects of resveratrol in this rat model [112].

Chemically linked to resveratrol, pterostilbene is a polyphenol that shows promising properties. Pterostilbene is found in certain berries, such as blueberries, grapes, and cranberries and, due to its high bioavailability, has gained attention due to its potential health benefits. In a hepatic context, two recent studies have shown its autophagic-dependent protective properties both in alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease. In ethanol-exposed hepatocytes, the treatment with pterostilbene restored the autophagic flux and activated Sestrin2 (SESN2)-induced p62-selective autophagy, leading to the reduction of cellular communication network factor 1 (CCN1) protein levels, an event correlated with the observed anti-senescent effects of pterostilbene [113]. Other study evaluated the effects of pterostilbene in HepG2 cells that were treated to accumulate lipids. The treatment with pterostilbene promoted the protein expression of AMPK, PI3K, ATG7, ATG16, ATG12, ATG15 and Beclin-1 and the transformation of LC3I to LC3II. Interestingly, this effect was abrogated in the NRF2 knockout cells, suggesting that his effector mediates the pterostilbene-mediated activation of autophagy [114].

Research indicates that phenolic acids possess the capability to regulate the intricate process of autophagy in liver cells. Rosmarinic acid, a polyphenol found in rosemary and other plants from the Lamiaceae family, is therapeutic against liver steatosis. 20 µM Rosmarinic acid counteracted the levels of intracellular ROS, triglyceride levels, reduced steatosis-linked ER stress, and enhanced the protein levels of Beclin-1, ATG5, ATG7, and LC3-II in oleic acid-treated HepG2 cells [115]. In AML-12 mouse hepatocytes exposed to palmitate, ferulic acid significantly ameliorated lipotoxicity hallmarks in cells. 100 µM ferulic acid stimulated SIRT1-mediated autophagy. The silencing of this gene by siRNA resulted in the abrogation of most of the therapeutic effects of this polyphenol [116]. Ferulic acid is also capable of counteracting the liver toxicity associated with acetaminophen, one of the most used analgesics. Chowdhury et al. [117] demonstrated that ferulic acid alleviates hepatocyte apoptosis, and mitochondrial damage and stimulates AMPK-dependent autophagic flux in isolated hepatocytes. Finally, curcumin has shown an interesting potential in the alleviation of hepatic fibrosis. In vivo, curcumin activated AMPK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR-dependent autophagy, and this event is correlated with the reduction of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocytes [118].

Renal disorders represent a major worldwide health concern and comprise a wide spectrum of conditions affecting the kidneys. These organs are crucial for controlling electrolyte balance, eliminating waste and extra fluid from the blood, and generating hormones needed for many body processes. Acute or chronic renal dysfunction can result in several problems that negatively impact general health and well-being. Numerous variables, such as genetics, infections, autoimmune illnesses, hypertension, diabetes, exposure to specific drugs or chemicals, and diabetes, can cause renal problems [124]. These illnesses show up in a variety of ways, from minor irregularities in the urine to serious renal failure that calls for dialysis or kidney replacement. Comprehending the underlying processes, risk factors, and therapeutic techniques for kidney illnesses is essential.

Current literature evidences that autophagy is instrumental in maintaining renal homeostasis and the deficit of autophagy might be behind the development of acute and chronic renal diseases. Some renal cell types, such as podocytes, possess high levels of homeostatic autophagy [125]. In a healthy kidney, basal autophagy acts as a cytoprotective molecular mechanism. Autophagy participates in kidney tubular maintenance, protects against oxidative stress, contributes to kidney development, and attenuates inflammatory responses [126, 127, 128, 129]. Furthermore, several studies in which renal autophagy is suppressed at some point show that this process is imperative for the correct functioning of the kidney [130, 131, 132]. In the renal context, as in many other pathological contexts, autophagy can be positive or detrimental depending on the disease, the stage of the pathological process, and the cell type. Due to its importance in renal physiology, autophagy has been proposed as a therapeutic axis in many renal diseases, such as sepsis-induced kidney injury, ischemia/reperfusion kidney injury, kidney fibrosis, and diabetic nephropathy, among others [133]. Interestingly, age emerges as a crucial regulator of renal autophagy and autophagic decline is a classic hallmark in aged kidneys [134, 135]. Of note, the protective effects of natural polyphenols are starting to be exploited, especially in diabetic nephropathy complications [135]. In this section, we summarize the current scientific knowledge that, to date, showcases the therapeutic use of polyphenols as autophagy modulators and their beneficial effect on renal diseases (Table 3, Ref. [116, 123, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155, 156, 157]).

| Family | Polyphenol | Dose | Model of the study | Disease | Signaling pathway | Reference |

| Flavonoid | Quercetin | 30 µM | LLC-PK1 cell line | Renal ischemia-reperfusion injury | AMPK-mTOR | [136] |

| 5 and 10 mg/kg | Mice | |||||

| 50 mg/kg | Mice | DKD | - | [137] | ||

| 50 µM | Mouse podocytes | |||||

| 0.2% in diet | Mice | Renal protection | Akt-mTOR | [138] | ||

| Rutin | - | Mice | DKD | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [139] | |

| GEnCs | ||||||

| 150 mg/kg | Rats | Gentamicin-induced renal damage | - | [140] | ||

| Kaempferol | 1, 2 and 5 µM | Mesangial cells | DKD | - | [141] | |

| 50 and 100 mg/kg | Mice | DKD | AMPK-mTOR | [142] | ||

| Genistein | 20 µM | Renal podocytes | DKD | mTOR | [143] | |

| Luteolin | 100 mg/kg | Mice | Angiotensin II-induced renal damage | - | [144] | |

| Baicalein | 0.15 g/kg | Carp | Chlorpyrifos-derived renal damage | PI3K/AKT | [145] | |

| 25 and 50 µmol/L | Canine Renal Tubular Epithelial Cells | Cisplatin-derived renal damage | AMPK-mTOR | [146] | ||

| Hesperidin | 100 and 200 mg/kg | Rats | Sodium fluoride-induced renal damage | - | [123] | |

| EGCG | 20 µM | HEK293T cells | Endoplasmic reticulum stress | AMPK-mTOR | [147] | |

| Stilbenes | Resveratrol | 10 mg/kg | Mice | DKD | - | [148] |

| 5, 10 and 15 µM | Human podocytes | |||||

| 5 mg/kg | Rats | DKD | SIRT1 | [149] | ||

| - | NRK-52E cells | Hypoxia | ||||

| 10 mg/kg | Rats | Kidney calcium oxalate (CaOx) stone formation | TFEB | [150] | ||

| 32 µmol/L | NRK-52E cells | |||||

| - | Human kidney proximal tubular epithelial cell | Chronic kidney disease | - | [151] | ||

| line HK-2 | ||||||

| Pterostilbene | 2 µM | NRK-52E cells | Chronic kidney disease | - | [152] | |

| 200 mg/kg | Mice | Hyperuricemia | ||||

| Phenolic acids | Rosmarinic acid | 100 mg/kg | Rats | Gentaminic-induced toxicity | - | [153] |

| Ferrulic acid | 200 mg/kg | Mice | DKD | - | [147] | |

| 50 mg/kg | Rats | DKD | MAPK | [116] | ||

| 5, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 200 µM | NRK-52E cells | |||||

| Mangiferin | 12.5, 25 and 50 mg/kg | Rats | DKD | AMPK-mTOR-ULK1 | [154] | |

| Other polyphenols | Curcumin | 300 mg/kg | Rats | Heymann nephritis | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | [155] |

| Nrf2/HO-1 | ||||||

| 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 µmol/L | Human kidney tubular epithelial cells (HKCs) | Renal fibrosis | Akt/mTOR | [156] | ||

| 200 mg/kg | Mice | DKD | - | [157] | ||

| 20, 40 and 80 µM | MPC5 cells |

DKD, diabetic kidney disease; AMPK-mTOR, AMP-activated protein kinase - mechanistic target of rapamycin; PI3K/AKT/mTOR, phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/mechanistic target of rapamycin; HEK293T, human embryonic kidney 293T Cells; NRK-52E, Normal Rat Kidney Epithelial Cells; SIRT1, Sirtuin 1; TFEB, transcription factor EB; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; Akt/mTOR, protein kinase B/mechanistic target of rapamycin.

Quercetin is starting to be explored in renal diseases regarding the modulation of the autophagic function in single or in combinatory strategies. Chen et al. [136] tested the therapeutic potential of quercetin against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury using porcine renal proximal tubule cell line (LLC-PK1) cells and C57BL/6j mice. In the in vitro model, 30 µM quercetin protected against renal cell apoptosis, and this effect was mediated, at least in part, by AMPK-dependent autophagy. 5–10 mg/kg quercetin decreased the phosphorylation of mTOR, increased the phosphorylation of AMPK, activated autophagy (measured by LC3 immunofluorescence), and offered renal protection in vivo [136]. Interestingly, quercetin has been tested in combination with dasatinib, a kinase inhibitor drug used for the treatment of some leukemias, for treating diabetic kidney disease. In vivo, this combinatorial therapy, upregulated autophagy (measured by LC3 and p62 immunofluorescence and western blot and showed promising effects regarding kidney physiology in urine albumin-creatinine ratio, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen. Both in vivo and in vitro, the formulation reduced podocyte differentiation under high glucose conditions. In vitro, the autophagic process participates actively in this suppression [137]. Interestingly, Sato et al. [138] demonstrated that when an adult female mice offspring is fed a high-fructose diet, the consumption of quercetin by the mother during breastfeeding may result in long-term changes in the kidneys’ autophagy flux and inflammation.

Additionally, the flavonol glucoside rutin has demonstrated potential as a treatment for diabetic nephropathy. Rutin activated autophagy and attenuated the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, a key hallmark of the disease, both in a mouse model of diabetic nephropathy and in high glucose-induced human renal glomerular endothelial cells. Dong et al. [139] demonstrated that the autophagic modulation was mediated by the mTOR-linked histone deacetylase 1 (HDCAC1) inhibition. By contrary, other authors claim that rutin might be protective through autophagy inhibition in specific conditions. In a rat model of gentamicin-induced renal damage, rutin reduced renal damage as show biochemical parameters such as creatinine, glutathion (GSH), MDA levels, and SOD, catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity, inflammation, and apoptosis. However, although the authors suggested that rutin downregulates the autophagic process, further studies would be needed to draw that conclusion [140].

There are also a few studies available regarding the use of kaempferol to modulate autophagy in nephropathies, and these correspond to diabetic-related renal complications. In mesangial cells, kaempferol counteracted the advanced glycation end products (AGEs) formation, cell apoptosis, and mitochondrial depolarization. By using 3-MA, Zhang et al. [141] reported that autophagy is involved, at some level, in the protective mechanism of kaempferol. 50 mg/kg/day kaempferol for 12 weeks ameliorated some pathological kidney changes such as the mesangial matrix expansion, glomerular basement membrane thickening, reduced podocyte injury, diminished renal apoptosis and enhanced autophagy (seen as Western blotting analysis of upregulated LC3II, Beclin-1, ATG7 and ATG 5, and downregulated p62) in a mouse model that recapitulate the hallmarks of diabetic nephropathy. Despite these results display a promising landscape, more experiments would be necessary to directly associate the protective activity of kaempferol with autophagy [142].

Despite the available information is limited, genistein-induced autophagy has

also been tested as a possible therapy approach for renal disease management. 20

µM genistein reversed the worsening of some fitness podocyte

parameters such as synaptopodin and nephrin and increased the mTOR-mediated

autophagy in an immortalized mouse podocyte cell line cultured in high glucose

conditions [143]. Also, luteolin was tested as a therapeutic agent in an

angiotensin II (AngII)-induced renal damage mice model. Luteolin, administered by

oral gavage at a dose of 100 mg/kg/day, alleviated the AngII-mediated

proinflammatory state in the kidney tissues (gene expression of IL‑1

The flavonoid baicalein is currently under investigation as a potential

treatment for acute kidney damage induced by toxic substances. 25–50

µmol/L of baicalin for 24 h treatment counteracted the levels of some

inflammatory factors such as TNF-

Although hesperidin, a phenolic substance derived from citrus fruits can modulate autophagy in pathological contexts [158, 159], there is only one study targeting renal physiopathology and the autophagic process. In rats with sodium fluoride-induced toxicity, hesperidin ameliorated kidney damage, improved the apoptotic markers, and stimulated autophagy by the upregulation of LC3A, LC3B, and Beclin-1 [123].

As in previous chapters, resveratrol represents one of the polyphenols with a

higher capacity for modulating autophagy in a nephropathological context.

Firstly, resveratrol has been proven to be effective against diabetic

nephropathy, 10 mg/kg/day resveratrol for 12 weeks significantly decreased

podocyte apoptosis, reversed histological damage and ameliorated the glomerular

lesion in an in vivo model of the disease [148]. In this model, the

autophagic process was increased (as shown by LC3-II immunofluorescence and

LC3-II, p62, and ATG5 protein levels), and this enhancement seems to be modulated

by the resveratrol-mediated suppression of miR-383-5p. In vitro, 15

µM resveratrol decreased cell apoptosis in high-glucose-treated podocytes

and activated autophagy. By suppressing autophagy using, 3-MA and Atg5-shRNA, the

authors found that the protective effects of resveratrol vanished [148]. In

another rat model of diabetic nephropathy subjected to hypoxia, 5 mg/kg/day

resveratrol enhanced autophagy measured by Western Blot and quantitative

polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) of LC3, ATG5, ATG7, FOXO3, and BNIP3 in the

kidneys of those animals, attenuated inflammation and renal dysfunction and

stimulated SIRT1 expression. The influence of SIRT1 was confirmed using normal

rat kidney epithelial cells (NRK-52E) cells exposed to hypoxia. The inhibition of

this autophagic effector abrogated the resveratrol-mediated autophagic

enhancement in these cells [149]. Resveratrol can also exert its effects by

regulating the TFEB-induced autophagy pathway. In glyoxylic acid

monohydrate-induced rats, an in vivo model of kidney calcium oxalate

(CaOx) stone formation, the authors analyzed the therapeutic effects of

intragastric administration 10 mg/kg/day resveratrol. Resveratrol was effective

in decreasing inflammation, the production of ROS species, and the kidney CaOx

crystal deposition and increased autophagy was shown by transmission electron

microscopy. To further investigate the effects of resveratrol in this

nephropathy, the authors treated NRK-52E cells with oxalate and 32

µmol/L resveratrol. The protective effects of resveratrol were

analogous to those observed in vivo, and by using 3-MA and TFEB

inhibitors, Wu et al. [150] demonstrate that resveratrol can exert its

effects through TFEB-mediated autophagy. Interestingly, recent literature

evidence that resveratrol is starting to be tested in combinatorial therapeutic

approaches. Resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles conjugated to anti-kidney injury

molecule-1 antibodies suppressed NLRP3 inflammasome in a mouse model of chronic

kidney disease (CKD) and stimulated autophagy by modulating AMPK and AKT/mTOR

[151]. Pterostilbene, a stilbene analog to resveratrol, also activated autophagy

and targeted NLPR3 inflammasome activation. In NRK-52E cells, pterostilbene

inhibited TGF-

Another source of compounds that can be used to control the autophagic activity in nephropathies could be phenolic acids. Rosmarinic acid and lycopene alone and in combination showed promising effects against gentamicin-derived nephrotoxicity. Bayomy et al. [153] found that these bioactive compounds improved the histological damage, increased the expression of Bcl2, an antiapoptotic marker, decreased Bax protein levels, and proapoptotic marker, enhanced LC3/B expression, and decreased the elevated levels of blood urea nitrogen and renal malondialdehyde. It is yet unclear, nevertheless, how these substances’ beneficial benefits relate to the autophagic process. Ferrulic acid could represent a potential management strategy for diabetic nephropathy. In vivo, ferulic acid has the capacity of restore the autophagic process compromised in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and mice and offers renoprotection [117, 147]. In vitro, 75 µM ferulic acid administration to NRK-52E cells exposed to high glucose, had beneficial effects regarding apoptosis, oxidative stress, and autophagy. Interestingly, the blockade of autophagy abrogated the cell survival offered by ferulic acid [117].

Mangiferin, a polyphenol mainly found in Mangifera indica (Mango), is effective in preventing diabetic nephropathy progression. The chronic administration of 12.5–50 mg/kg/day mangiferin by oral gavage protected against diabetic-linked renal pathological lesions. Western blotting and TEM analysis revealed that the autophagic process was stimulated. Wang et al. [154] claimed that the autophagic regulation occurs via the AMPK-mTOR-ULK1 pathway, due to the increase of phosphorylation of AMPK and ULK1 and the decrease in the phosphorylation of mTOR. Despite its activity against many age-related disorders, the questions regarding the renoprotective potential of this bioactive polyphenol remain unanswered. However, this natural compound stimulates AMPK-mTOR autophagy and enhances HEK293T cell survival [160].

Finally, curcumin can modulate autophagy in renal diseases impacting different

molecular pathways. This polyphenol had therapeutic bioactivity in a rat model of

passive Heymann nephritis. 300 mg/kg/day curcumin administration diminished the

kidney pathological changes in the animals, ameliorated oxidative stress, and

increased the number of autophagic vacuoles, measured by a p62 immunofluorescence

assay. Based on Western blot analysis of a set of autophagic and antioxidant

proteins, the authors suggest that curcumin’s effect could be exerted through the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/Heme

Oxygenase-1 (NRF2/HO-1) pathways [155]. In another study, Zhu et

al. [156] suggested that curcumin modulates the AKT/mTOR pathway to avoid the

TGF-

Polyphenols represent a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention as potential modulators of autophagy in the context of cardiovascular, hepatic, and renal diseases. However, a critical examination of existing studies underscores a significant gap in research methodologies. Many investigations, despite demonstrating the influence of polyphenols on autophagic factors, often fall short of providing comprehensive assessments of autophagy flux. The absence of experiments utilizing autophagic inhibitors or genetic inhibition of autophagy to validate the modulation of autophagy raises concerns about the robustness and specificity of the reported findings. Most of the studies in bibliography described steady-state levels of autophagic proteins, including ATG5, LC3 or p62 [161]. Although alterations of these markers could be indicative of changes in autophagic function, dynamic assays to monitor quantitively autophagic degradation will be necessary to accurately quantify the potential of polyphenol on autophagic function.

Additionally, a significant challenge in advancing the clinical application of polyphenols for modulating autophagy lies in the lack of reliable techniques to directly measure autophagy in humans. Currently, most methods to assess autophagy are based on cellular or animal models, where markers such as LC3-II levels or autophagosome counts can be readily quantified [162]. However, translating these findings to human studies is problematic due to the absence of non-invasive, standardized methods to accurately measure autophagic activity in vivo [163, 164]. This limitation has resulted in a scarcity of clinical trials specifically assessing autophagy as an endpoint, thereby hindering our understanding of how polyphenols and other interventions impact this crucial cellular process in human health. Other issues regarding the use of polyphenols could be that both the therapeutic doses of different polyphenols and the lack of studies evaluating synergistic effects of combinatorial treatments. Of note, a low dose of polyphenol could enhance the autophagic process while a high dose of the same phytocompounds could suppress the degradative pathways. Further experimental design should be performed in the future to characterize optimal polyphenol dosage and biological impact on autophagic routes.

The use of polyphenols as therapeutic agents in human pathologies entails several challenges that need to be addressed. Polyphenols are characterized by their low bioavailability [165]. Their absorption by the gastrointestinal is often poor, and these molecules tend to be degraded easily due to their high chemical instability. Polyphenols are constantly subjected to modifications due to their interaction with the gut microbiota and other bioactive molecules [166]. Additionally, interindividual variability in effects, and a lack of robust clinical evidence makes that further studies will be required to establish optimal therapeutic doses of different polyphenols and to optimize the use of this promising molecules in these pathological contexts.

It is to note that the aim of this review is to compile and synthesize all available information from the literature regarding the activation of autophagy by polyphenols within the context of age-related processes. The focus is on gathering and presenting the current understanding of how polyphenols influence autophagy as a potential mechanism for mitigating age-associated cellular and physiological decline. This review does not intend to assess the quality of the experimental designs, or the appropriateness of the statistical approaches used in the studies. Instead, it seeks to provide a comprehensive overview of the findings, irrespective of the methodologies employed, to better understand the potential role of polyphenols in promoting healthy aging through autophagy activation.

Conceptualization (EB and LGM); Investigation (APM, NAS, ADB, AL, EB and LGM); Visualization (APM, NAS); Writing — original draft preparation (APM, NAS, EB and LGM); Writing — review and editing (ADB and AL); Supervision (EB and LGM); Funding acquisition (EB and LGM). All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to its accuracy or integrity. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by RYC2018-024434-I, MINECO PID2023-151873OB-I00 (to EB) and IDOC23-06 (to LGM).

Given their role as the Guest Editor member, Eloy Bejarano and Lucia Gimeno-Mallench had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Kavindra Kumar Kesari. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.