1 Laboratory of Applied Metabolomics and Pharmacognosy (LAMP), Institute of Evolution, University of Haifa, 3498838 Haifa, Israel

Academic Editor: Jen-Tsung Chen

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided an opportunity for repurposing of drugs, including complex, natural drugs, to meet the global need for safe and effective antiviral medicines which do not promote multidrug resistance nor inflate medical costs. The author herein describes his own repurposing of herbal tinctures, previously prepared for oncology, into a possibly synergistic, anti-COVID 41 “herb” formula of extracts derived from 36 different plants and medicinal mushrooms. A method of multi-sample in vitro testing in green monkey kidney vero cells is proposed for testing the Hypothesis that even in such a large combination, antiviral potency may be preserved, along with therapeutic synergy, smoothness, and complexity. The possibility that the formula’s potency may improve with age is considered, along with a suitable method for testing it. Collaborative research inquiries are welcome.

Keywords

- botanical

- harmine

- licorice

- medicinal mushroom

- Peganum harmala

- synergen

- virus

- virucidal

When the reality of the pandemic really hit home in March 2020 at the time of our first national “lockdown”, I had, stashed away in my subterranean laboratory numerous containers of medicinal herbs and their concentrated tinctures that I had prepared over the previous year for use with oncology patients. I began to wonder if any of that could be “repurposed” as antivirals against COVID-19. But when two totally unrelated friends from vastly different places, times, and contexts independently contacted me, a physician-pharmacognosist, around the same time asking if I had any herbal solution for COVID, I went down to the lab to see what I could do with what I had. Upstairs, I also had the computer to search the Internet and literature of the world.

I discovered, for example, that among COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China, 91% had received Chinese herbal medicines as part of their hospital therapeutic programs [1].

Redundancy, required for synergy, may benefit medical interventions just as it may benefit viruses [2, 3].

In phytotherapy, synergy may be “pharmacodynamic” affecting multiple targets; “pharmacokinetic” by improving drug transport, permeation, and bioavailability; diminishing side effects; or deactivating drug resistance [4]. Plant drugs may inhibit target-modifying and drug-degrading enzymes, or inactivate cellular efflux pumps [5].

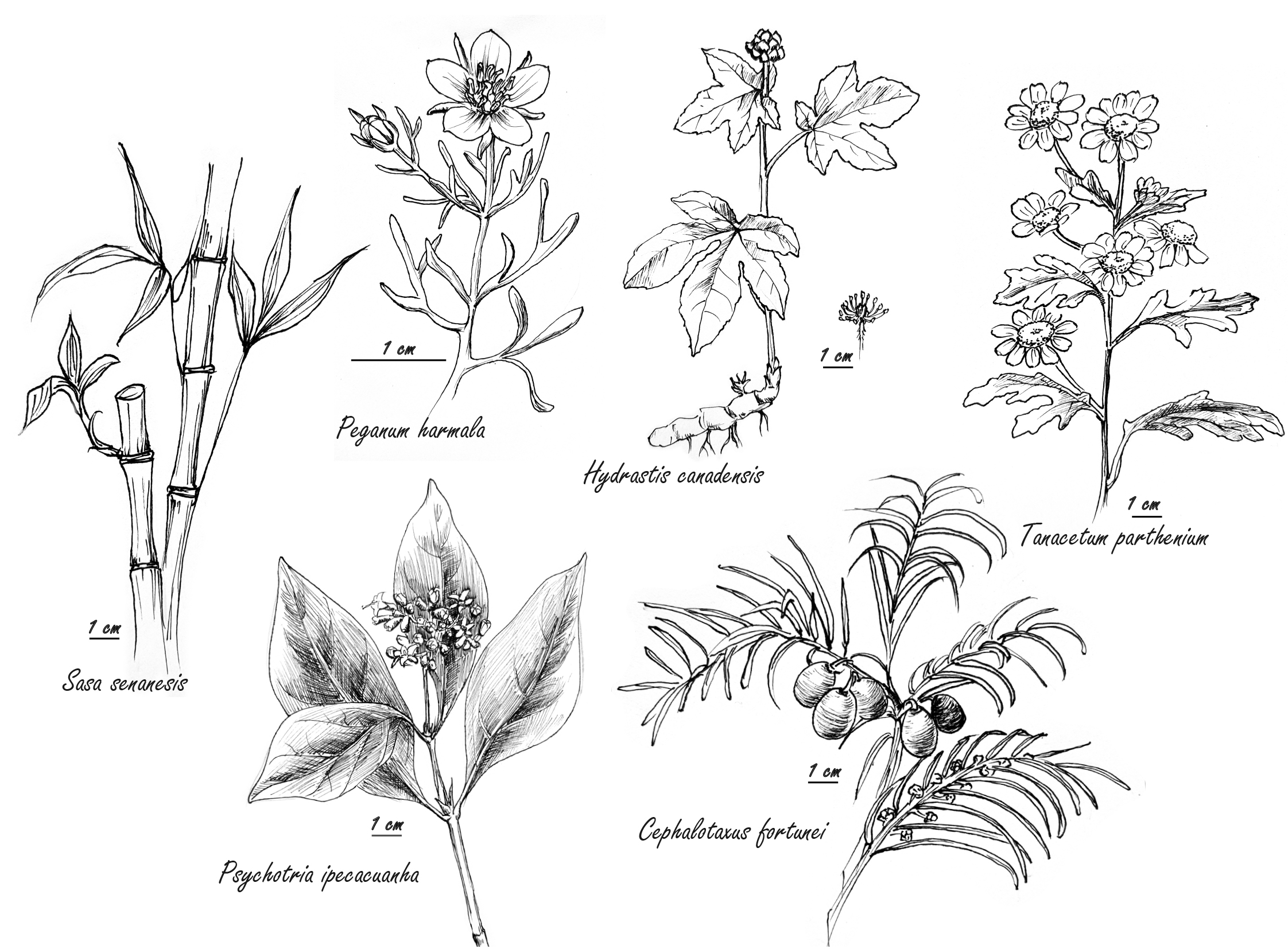

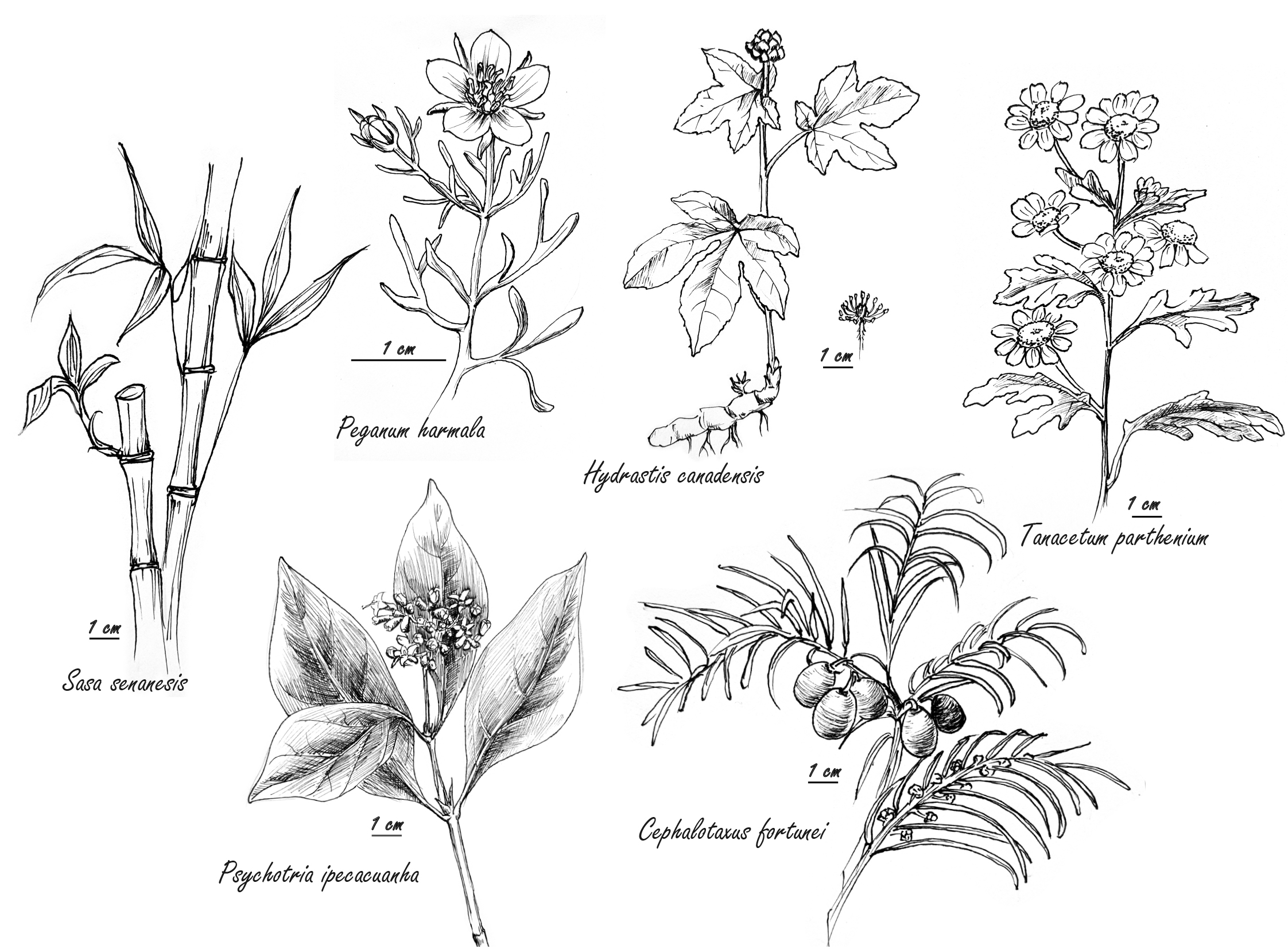

Harmine, from the methanolic extract of Peganum harmala (Fig. 1) seeds, synergized with the conventional antiviral agent acyclovir against human Herpes simplex virus Type 2 in vitro. The P. harmala extract alone, though not cytoprotective, was virucidal both during the entry of viruses and during release of newly formed virions [6]. Similarly, an alkalized aqueous extract of the leaves of Sasa senanesis synergized in vitro with acyclovir against herpes simplex virus, while alone, S. senansis suppressed human immuno-virus (HIV) [7].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Selected herbs with antiviral properties cited in text or tables.

Different natural products from a single plant or medicinal mushroom may also

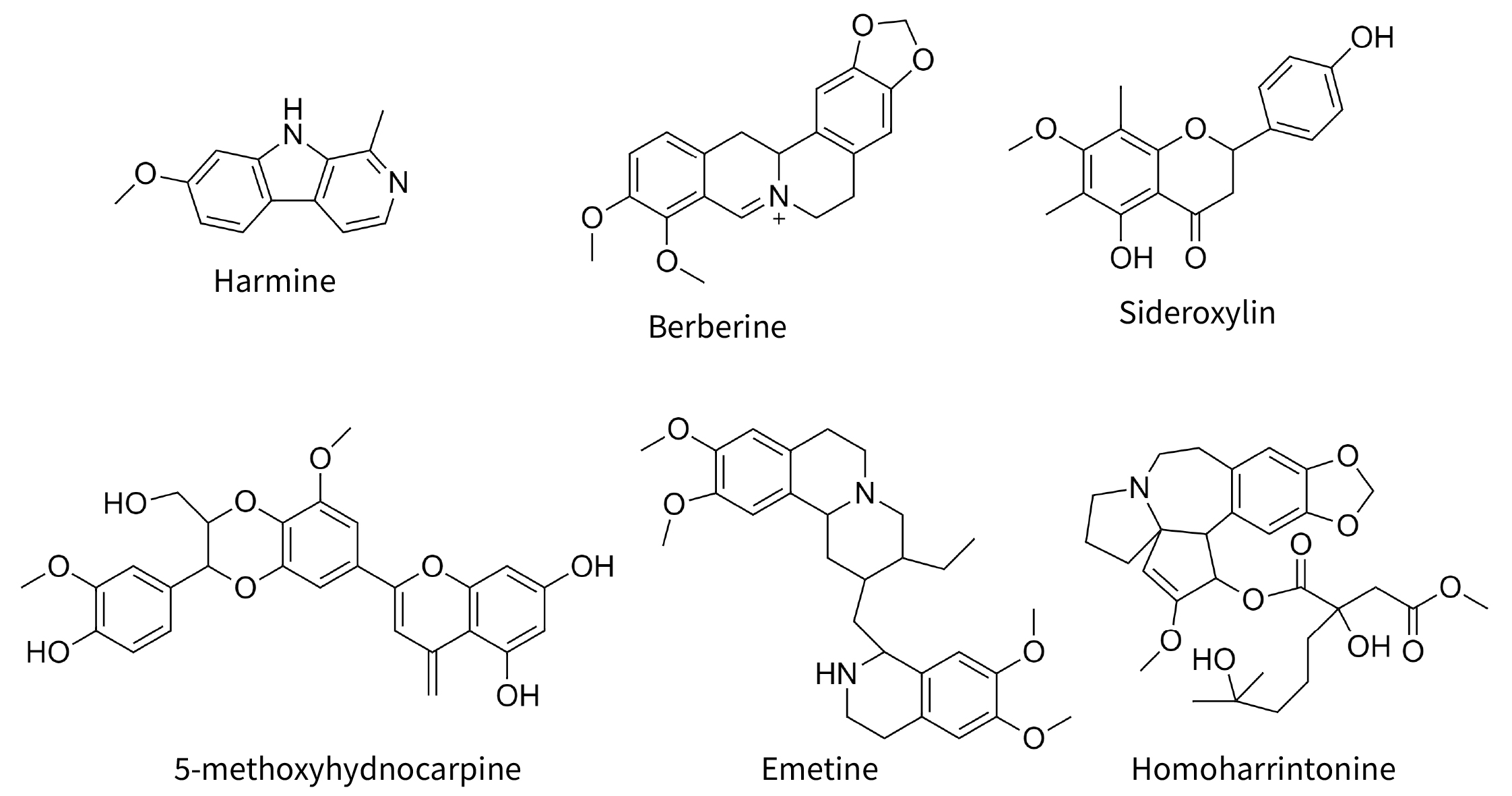

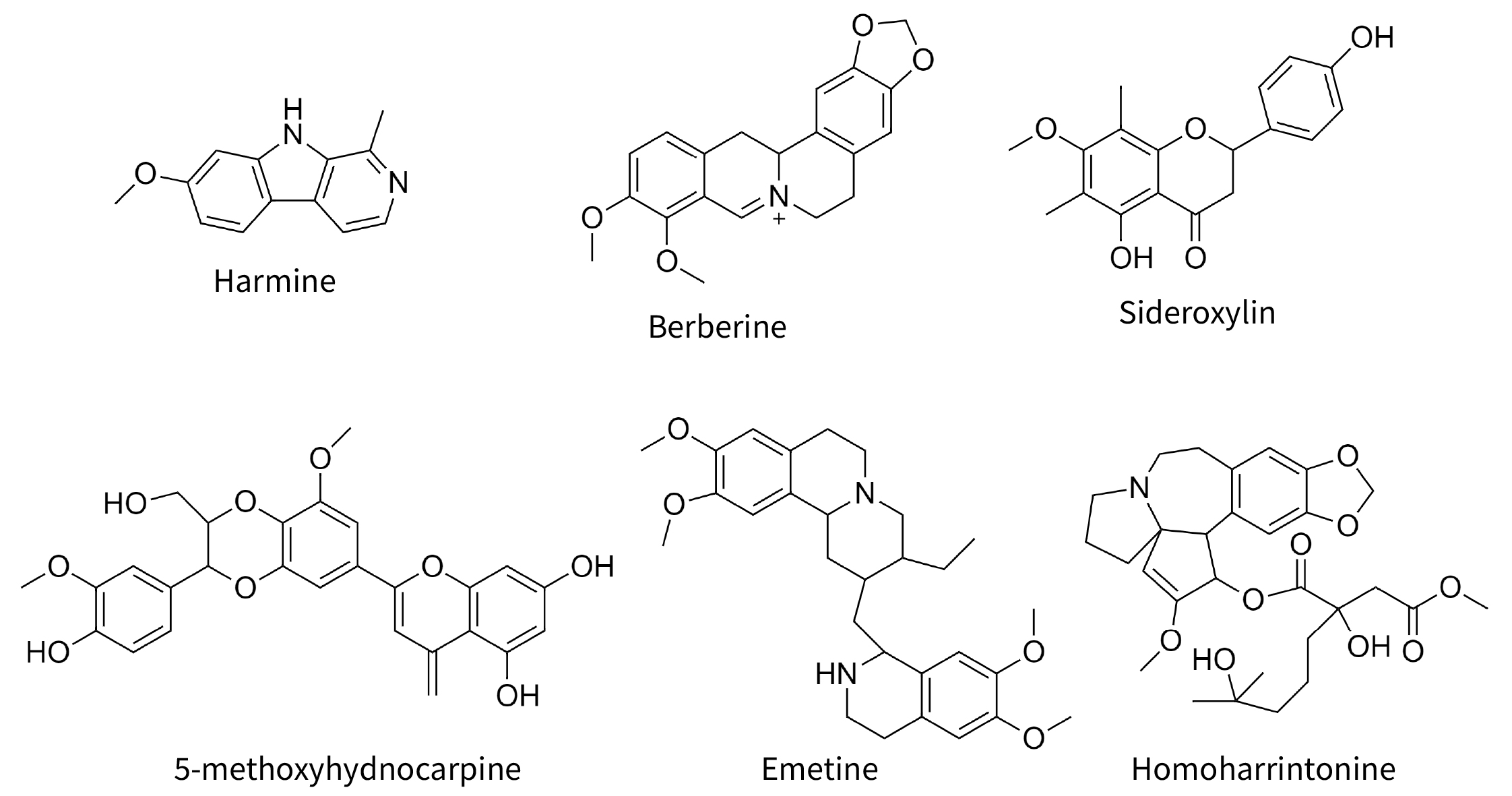

synergize with each other. Berberine (Fig. 2) an alkaloid prominent in

the yellow roots of Coptis chinensis and goldenseal,

Hydrastis canadensis, is typically regarded as the “active”

in these plants, but when the complex H. canadensis extract, or its

isolated novel flavonoid, 3,3’-dihydroxy-5,7,4’-trimethoxy-6,8-C-dimethylflavone,

itself without antibiotic activity is combined with berberine, the effective

antibiotic dose (IC

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Selected molecules cited in text. Harmine and berberine are common alkaloids with antiviral properties. The other four compounds are synergens, not antiviral in themselves, but increasing the antiviral potency of true antiviral compounds.

Synergy may occur in phytochemical interactions within and between different foods to improve or weaken their medicinal potency and utilization [11, 12]. Improvement of solubility of a complex often improves its absorption and so augments synergies [13].

To measure synergy within a super-complex mixture of three complex mixtures all

derived from the same pomegranate fruits (Punica granatum), we used a

simplified method. Extracts from pomegranate seeds (pressed oil), peels (aqueous

extract), and juice (fermented, concentrated, and extracted with ethyl acetate)

were tested individually and in combinations for their ability to inhibit

invasion of human PC-3 human prostate cancer cells in vitro. We fixed a

dry weight dosage of each component to 1 mg/1 mL medium. This 1 mg was constant

whether 1 component, 2 components, or 3 components were tested, which were equal

in % dry weight to each other. Using this assessment, each component, used

alone, effected an approximately 60% inhibition of invasion. When oil and peel,

or oil and fermented juice components were combined in a 1:1 ratio totaling 1

mg/mL, we observed a 90% inhibition. When we combined equally all three

components, oil, peel extract, and fermented juice extract to total 1 mg/mL, we

found

Pure compounds can be quantified with molarity, but complex botanical extracts can only be measured by dry weight. In the above example, an isobologram assessment for the fermented juice and peel fractions is feasible since their largely overlapping chemistry is aimed at common targets. However, because the oil’s chemistry is so different, and likely involves different mechanisms and targets for its physiological effects than peel or juice, isobologram assessment was unsuitable for measuring the combination effect between the pomegranate’s lipid and aqueous compartments [16]. In general, synergy involves different sites of actions, while simple addism serves same sites of action [17].

Herbal synergy may describe synergistic interactions between phytochemicals within a single herb, and/or synergistic effects between different herbs in a single formula [18]. Prescribing different drugs together to achieve synergistic benefits is common practice with antimycotics [19]. In nutrition, synergy among fruits and vegetables, which may be intensified or modulated during intestinal absorption, improves or impairs their overall clinical effectiveness [20]. Further, synergistic mixtures require lower levels of use with superior efficacy [21]. The concept of synergy, i.e., a whole or partially purified extract of a plant being better than a single isolated ingredient, underlies the philosophy of herbal medicine [22].

Similar to the pomegranate synergy described above, three different fractions, namely alkaloids, lignans, and organic acids of the roots of Isatis tinctoria were evaluated for antiviral activity against respiratory syncytial virus in a mouse model. Each fraction exhibited antiviral properties, the strongest effect was when all three fractions were combined [23].

In the past, combination treatments for influenza were favored if they did not contribute to the emergence of drug resistant strains of virus or result in increased costs of treatment. If they did not prolong the virus’s eclipse phase, they were required to be used in combination with antiviral drugs that did [24].

The plant alkaloids emetine, from Psychotria ipecacuanhaand homoharringtonine, fromCephalotaxus fortunei synergized with the broad spectrum antiviral, Remdesivir, or the anti-HIV retroviral, Lopinavir, against SARS-CoV-2 [25]. Synergy was observed between hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as probable competitive inhibitors to the SARS-CoV-2 virus at the host’s cell membranes [26]. Synergy was also central to a proposal for testing various deoxynucleosides with 5-fluorouracil which had become ineffective when used alone due to coronavirus recognition [27]. Recent three dimensional methods have been advanced to quantify synergy between different modern antiviral drugs, which could be as high as 180 fold when stimulated by a synergen [28, 29].

Many papers were published over the past two years regarding herbal treatments or potential treatments for COVID-19 [30, 31]. A sampling of this research, presented according to plant name, is presented in Table 1.

| Number | Latin name of the source of the crude drug | Reference(s) |

| i | Acanthopanacis gracilistylus | [41] |

| ii | Aconitum lateralis | [42] |

| iii | Adenophora stricta | [43] |

| iv | Agastache rugosa | [43] |

| v | Aglaia sp. | [41] |

| vi | Alhagi pseudalhagi | [41] |

| vii | Allium porrum | [41] |

| viii | Alium ursinum | [41] |

| ix | Alstonia scholaris | [41] |

| x | Amelanchier alnifolia | [41] |

| xi | Ammi visnaga | [45] |

| xii | Anemarrhena asphodeloides | [46] |

| xiii | Angelica sinensis | [41, 47, 51] |

| xiv | Anthemis hyaline | [41] |

| xv | Arctium sp. | [48] |

| xvi | Ardisia japonica | [46] |

| xvii | Armenia caramara | [49] |

| xviii | Aster tataricus | [41] |

| xix | Artemisia apiacum | [50] |

| xx | Astragalus membranaceus | [50, 51] |

| xxi | Atractylodes sp. | [50] |

| xxii | Bambusa sp. | [50] |

| xxiii | Benincasa hispida | [50] |

| xxiv | Boenninghausenia sessilicarpa | [41] |

| xxv | Broussonetia papyrifera | [41] |

| xxvi | Bupleurum chinense | [41, 50, 52] |

| xxvii | Camellia sinensis | [41] |

| xxviii | Cassia fistula | [41] |

| xxix | Cassia tora | [41] |

| xxx | Chrysanthemum sp. | [46, 50] |

| xxxi | Cibotium barometz | [41] |

| xxxii | Cibotium barometz | [41] |

| xxxiii | Cimicifuga racemosa | [41] |

| xxxiv | Cistanche sp.. | [41] |

| xxxv | Citrus sinensis | [41] |

| xxxvi | Cladrastis lutea | [41] |

| xxxvii | Codonopsis pilosula | [47] |

| xxxviii | Coix lacryma-jobi | [50] |

| xxxix | Corydalis bungeana | [53] |

| xl | Crocus sativus | [44, 45] |

| xli | Cymbidium sp. | [41] |

| xlii | Cyrtomium fortunei | [43] |

| xliii | Dendrobium nobile | [43] |

| xliv | Desmodium canadense | [41] |

| xlv | Dianthus sp. | [41] |

| xlvi | Dioscorea batatas | [41] |

| xlvii | Dryopteris crassi | [42, 54, 61] |

| xlviii | Ephedra sinica | [41, 46, 50, 54, 61] |

| xlix | Epipactis helleborine | [41] |

| l | Erigeron breviscapus | [46] |

| li | Eriobotrya japonica | [46] |

| lii | Eupatorium sp. | [43] |

| liii | Euphorbia helioscopia | [46] |

| liv | Fagopyrum cymosum | [46] |

| lv | Tussilago farfara | [64] |

| lvi | Foeniculum vulgare | [45] |

| lvii | Forsythia suspensa | [41, 45, 54, 56, 61] |

| lviii | Fortunes bossfern | [46] |

| lix | Fritillaria verticillata | [41] |

| lx | Galanthus nivalis | [41] |

| lxi | Gentiana scabra | [41] |

| lxii | Ginkgo biloba | [41, 51] |

| lxiii | Gleditsia spina | [62] |

| lxiv | Glycyrrhiza sp. | [41, 46, 50, 54, 56, 61, 69] |

| lxv | Griffithsia | [41] |

| lxvi | Gypsum Fibrosum | [41, 46, 45, 63] |

| lxvii | Hedysarum multijugum | [46] |

| lxviii | Heteromorpha sp. | [41, 43] |

| lxix | Hippeastrum sp. | [41] |

| lxx | Houttuynia cordata | [41, 45, 52, 54, 55] |

| lxxi | Hovenia dulcis | [46] |

| lxxii | Hymenaea verrucosa | [45] |

| lxxiii | Inula sp. | [46] |

| lxxiv | Isatis indigotica | [52, 53] |

| lxxv | Isatis tinctoria | [54, 61] |

| lxxvi | Laurus nobilis | [45] |

| lxxvii | Lavandula stoechas | [45] |

| lxxviii | Ledebouriella multiflora | [46, 56] |

| lxxix | Lepidium sativum | [56] |

| lxxx | Ligusticum striatum | [51] |

| lxxxi | Lindera aggregata , | [52] |

| lxxxii | Lonicera japonica | [41, 46, 51, 54, 56, 61] |

| lxxxiii | Lycoris radiata | [41, 52] |

| lxxxiv | Magnolia officinalis | [63] |

| lxxxv | Melia sp. | [41] |

| lxxxvi | Mentha haplocalyx | [50] |

| lxxxvii | Mentha piperita | [41] |

| lxxxviii | Morus nigra | [41] |

| lxxxix | Myrtus communis | [45] |

| xc | Narcissus pseudonarcissus | [41] |

| xci | Nepeta cataria | [46, 48] |

| xcii | Nerium oleander | [46] |

| xciii | Nicotiana tabacum | [41] |

| xciv | Nigella sativa | [41, 52] |

| xcv | Notopterygium forbesii | [51] |

| xcvi | Ophiopogon sp. | [63] |

| xcvii | Paeonia alba | [41, 57] |

| xcviii | Panax ginseng | [56] |

| xcix | Panax notoginseng | [43] |

| c | Panax quinquefolius | [63] |

| ci | Paris polyphylla | [42] |

| cii | Paulownia tomentosa | [41] |

| ciii | Pelargonium sidoides | [41, 52] |

| civ | Peucedanum sp. | [46] |

| cv | Phellodendron sp. | [41] |

| cvi | Phragmitis sp. | [43] |

| cvii | Pinellia sp. | [42] |

| cviii | Platycodon grandiflorus | [48, 50] |

| cix | Pogostemon cablin | [48, 54, 61, 63] |

| cx | Polygonatum multiflorum | [41] |

| cxi | Prunus armeniaca | [47, 50, 56, 63] |

| cxii | Prunus serrulata | [41] |

| cxiii | Psoralea corylifolia | [41, 51] |

| cxiv | Punica granatum | [41, 45] |

| cxv | Pyrrosia lingua | [52] |

| cxvi | Rehmannia glutinosa | [48] |

| cxvii | Rheum australe | [45] |

| cxviii | Rheum officinale | [41, 54, 55, 61] |

| cxix | Rheum palmatum | [41] |

| cxx | Rhodiola crenulata | [54, 61] |

| cxxi | Rosa nutkana | [41] |

| cxxii | Salvia miltiorrhiza | [41] |

| cxxiii | Sambucus formosana | [41] |

| cxxiv | Sambucus nigra | [41] |

| cxxv | Sauge officinale | [45] |

| cxxvi | Schizonepeta tenuifolia | [56] |

| cxxvii | Scrophularia scorodonia | [41, 43, 48, 52, 56] |

| cxxviii | Scutellaria baicalensis | [41, 44, 48, 53] |

| cxxix | Sophora flavescens | [41, 51] |

| cxxx | Sophora subprostrata | [41] |

| cxxxi | Stephania tetrandra | [41] |

| cxxxii | Strobilanthes cusi | [41] |

| cxxxiii | Tamaricis cacumen | [46] |

| cxxxiv | Tamarindus indica | [45] |

| cxxxv | Taraxacum mongolicum | [53] |

| cxxxvi | Thuja orientalis | [41] |

| cxxxvii | Thymus vulgaris | [41] |

| cxxxviii | Toona sinensis | [41, 64] |

| cxxxix | Torilis sp. | [41] |

| cxl | Torreya nucifera | [41, 52] |

| cxli | Trichosanthes sp. | [47] |

| cxlii | Tripterygium regelii | [41] |

| cxliv | Tripterygium wilfordii | [65, 66] |

| cxlv | Tulipa sp. | [41] |

| cxlvi | Urtica dioica | [41] |

| cxlvii | Veratrum sabadilla | [41] |

| cxlviii | Zingiber officinale | [41, 44, 52] |

| cxlix | Ziziphus jujuba | [41] |

When a wine or fine spirit ages, its chemistry becomes more complex, or alternatively, its complexity increases. Aggregates of polyphenols increase during aging, and are associated with increased pharmaceutical potency [32, 33]. One bottle of Pinot Noir recovered from a French wine cellar and estimated to be between 200 and 300 years old was reported to have a higher amount of such aggregates, with its resveratrol also preserved [34]. Although during vinification a maximum phenolic concentration is achieved in about nine days, the antioxidant properties can continue to increase for many years, presumably related to the formation of such aggregation of polyphenols [35] and additional changes in flavanols and anthocyanins with the subjective sense being being mellow and smooth [36]. In one recent study, aging in wine resulted in increased inhibition of topoisomerase-2 [37], an enzyme required for viral replication [38].

Complexity may also occur in pharmaceuticals when many, even thousands, of compounds constitute the drug. Such “complex drugs” have some advantages, such as being able to impact multiple targets at once, and being less likely to cause drug resistance [39].

When I made a pilot mixture of ethanolic extracts from the tissues of 34 different herbs and two mushrooms for preventing or treating COVID-19 two years ago, I was guided by several constraints. Initially, the first constraint was whether I had the herb or foodstuff in my possession, and later, whether I could obtain it during increasing COVID-19 restrictions. Second, was that the material must be legal. Use of certain herbs may be prohibited by law. Third, the herb should not be too toxic. And finally, if possible, the solution should taste good, or at least, not taste too bad.

In herbal therapeutics, herbs of specific “temperament” such as being hot or cold, are used to balance or correct their opposites in the “temperament” of a patient. However, when designing a formula aimed to suit all for a specific task (preventing or treating COVID-19), it should have “round edges” and be well tolerated by persons regardless of their individual “temperaments”. So it was in this spirit that I combined the mostly certified organic, and if not organic, then usually wildcrafted herbs in the original formulation. Those herbs, extracted and concentrated to fit in a 1 liter laboratory bottle, have now aged for almost two years. In their present form, they might offer a point of departure for further studies.

I hypothesize that the combination of 41 herbal extracts which I have designated as “Core-Own-A” (Table 2) will be more effective in preventing or diminishing COVID-19 viral infection than any single one of its components, or even of smaller combinations of its components. Furthermore, I hypothesize that the efficacy and synergy within the combination will be enhanced during its aging.

| Source | Crude part | % | Action | Reference(s) | ||

| (Roman Numeral Rankings in the second column are for building the progressive formulae for testing as described in the text.) | ||||||

| 1 | xxxiii | Acorus calamus | Dried rhizome | 1 | inhibition of early stage Dengue viral RNA replication in vitro | [67] |

| 2 | xxx | Angelica sinensis | Dried root | 3 | Inhibited murine leukemia virus replication in vivo and enhanced CD4(+)/CD8(+) ratio | [68] |

| 3 | ii | Astragalus membranaceus | dried root | 15 | Inhibited influenza virus growth in vitro | [69] |

| 4 | xxxii | Atractylodes macrocephala | Dried rhizome, atractylon | 3 | Alleviated influenza virus induced pulmonary injury; suppression of H3N2 growth | [70, 71, 77] |

| 5 | xxxi | Bupleurum falcatum | Dried root | 2 | Inhibited growth of Hepatitis C virus in vitro | [72] |

| 6 | xxix | Ceanothus americanus | Dried root | 1 | Novel alkaloids, ethnographic antiviral use | [73, 74] |

| 7 | x | Cinnamomum cassia | Dried stem | 1 | non-toxic inhibition of H7N3 bird flu virus in vitro | [75, 76, 77] |

| 8 | ix | Citrus reticulata | Dried pericarp | 6 | impaired respiratory syncytial virus replication and entry into human epithelial cells | [78, 79] |

| 9 | xxxiv | Commiphora myrrha | dried stem gum | 1 | virucidal for enveloped respiratory syncytial virus B | [79, 80] |

| 10 | xxviii | Cordyceps militaris | Dried fruiting body | 1 | Benefits mouse H1N1 2009 influenza survival, clinical COVID-19 convalescence | [81, 82, 83, 84, 85] |

| 11 | xxxxi | Curcuma longa | Dried rhizome | 0.2 | Higher affinity to SARS-CoV-2 “catalytic core” than standard antiretroviral Lopinavir | [86] |

| 12 | xxvii | Eleutherococcus senticosus | Dried root | 2 | RNA virus-specific inhibition of replication in RSV and influenza A | [87, 88] |

| 13 | xi | Eriobotrya japonica | Dried leaf | 2 | increasing cytokines and activating interferon gamma host antiviral defense | [89, 90] |

| 14 | xii | Forsythia suspensa | Dried fruits | 4 | improved outcome and less inflammation in influenza A infected mice | [58, 59, 62, 63, 91, 92, 93, 94] |

| 15 | xiii | Ginkgo biloba | Dried leaf | 2 | inhibiting H3N2 influenza A 1968 pandemic virus, via inhibition of reverse transcriptase | [95, 96, 97, 98] |

| 16 | i | Glycyrrhiza glabra | Dried roots | 4 | inhibition of SARS-associated coronavirus isolates main viral protease inhibition; blocks viral cell attachment | [59, 60, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 196] |

| 17 | xxxv | Humulus lupulus | Dried flowers | 1 | suppression of 5 H1N1 and H7N1 influenza A strains via redox disruptions | [111, 112] |

| 18 | xxvi | Houttuynia cordata | Dried rhizome | 1 | inhibition of SARS-CoV 3C-like protease and RNA polymerase in vitro | [113, 114, 115] |

| 19 | viii | Hypericum perforatum | Dried aerial parts | 3 | Blocks angiotensin-converting enzyme type 2 receptor, key entry of SARS-CoV-2, dose dependently inhibited its replication | [96, 97, 98, 99, 116, 117, 119] |

| 20 | vii | Isatis tinctoria | Dried root | 3 | Strong anti-SARS-CoVs-3CL protease, inhibits hepatitis b virus in vitro | [55, 61, 120, 121, 122] |

| 21 | xiv | Ledebouriella seseloides | Dried root | 4 | Strong inhibition of novel coronavirus, influenza virus, long history of safe use | [123, 124] |

| 22 | xxv | Lentinula edodes | Dried fruiting body | 0.5 | reduced phagocytic index in vitro, possible preventive of Covid-19 cytokine storm | [125, 126] |

| 23 | xv | Lonicera japonica | Dried flowers | 1 | use against SARS coronavirus and H1N1 swine flu | [59, 127, 128, 129] |

| 24 | xxxvi | Mentha piperita | Dried leaf | 2 | Reduced inflammatory response to RSV in vitro, anti HIV, good taste, promotes patient compliance | [130, 131, 132] |

| 25 | xxxx | Musa acuminata | Dried peels | 3 | Anti HIV lectins, sweet taste | [133, 134] |

| 26 | xxxvii | Olea europaea | Dried leaf | 2 | Anti HSV, anti EBV, anti HSV, anti influenza in vitro | [135, 136, 137, 138, 139] |

| 27 | xxxviii | Oldenlandia diffusa | Dried leaf | 1 | Contains cyclotides with anti HIV | [140] |

| 28 | xvi | Panax ginseng | Dried root | 1 | Prevents viral respiratory infections, possibly also COVID cytokine storm, anti HSV, reduces viral virulence | [59, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147] |

| 29 | xxii | Peganum harmala | Seeds | 0.1 | Anti influenza virus, anti HSV2, possible role in COVID | [148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154] |

| 30 | vi | Pueraria lobata | Dried root | 4 | Inhibits influenza virus neuraminidase, in silico targeting of COVID-19 targets, suppression of HIV attachment | [155, 156, 157] |

| 31 | xvii | Punica granatum | Dried pericarps | 1 | Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 spike binding to human ACE2 receptor (in vitro), virucidal to many viruses | [158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169] |

| 32 | xviii | Punica granatum | Dried flowers | 1 | Rich source of oleanolic and ursolic acids, inhibitors of COVID-19 main protease, SARS-CoV-2 entry and associated inflammation | [168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175] |

| 33 | v | Sambucus nigra | Dried fruits | 4 | Widely used, safe antiviral, studies in COVID warranted, pleasant taste | [160, 174, 175, 176, 177] |

| 34 | xix | Sambucus nigra | Dried flowers | 1 | Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 S1 protein receptor binding domain, safe, wide use as antiviral, reduces inflammation | [178, 196] |

| 35 | xxxix | Schisandra sinensis | Dried fruits | 2 | Contains lignans with anti-HIV activity | [179, 180] |

| 36 | iii | Scutellaria baicalensis | Dried roots | 4 | Acts on multiple signaling pathways to reduce COVID-19 related organ damage, inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 3C-like protease | [61, 181, 182, 183, 184, 185, 186] |

| 37 | xx | Taraxacum officinale | Dried roots | 2 | Inhibition of replication of dengue, HCV, HBV, HIV, influenza viruses; benefits oxidative stress in liver and kidney, possible interference with SARS-CoV-2 attachment | [61, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192] |

| 38 | xxiii | Tripterygium wilfordii | Dried root | 0.1 | Potential for anti-SARS-CoV-2 Rx | [65, 66] |

| 39 | xxiv | Tripterygium wilfordii | Dried stem | 0.1 | Similar to root | [193, 194] |

| 40 | xxi | Urtica dioica | Dried leaves | 1 | Novel inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor; adjunct rx for COVID-19 | [195, 197] |

| 41 | iv | Zingiber officianale | Fresh rhizome | 8 | Extremely safe, most loved spice/herb worldwide, anti-viral, anti-influenza, stomachic, COVID-19 drug lead studies ongoing | [49, 118, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 202] |

The testing will:

1. Be able to ascertain the relative anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect (while not killing the host cell) of each of the 41 herbs from Table 2.

2. Show at which point in the complexity (i.e., higher N of herbs) either the synergism or dilution of the anti-SARS-CoV-2 effect is first noted. If it diminished, was it the increased increment of complexity, or the specific herb added at that time? Findings would point the way to further studies for more precise definition.

I propose a rapid screen of in vitro antiviral activity in standard SARS-CoV-2 infected green monkey kidney vero cells. In addition to controls which will be infected but not treated, these infected cells will be subjected to 83 different herbal interventions aimed at preventing or inhibiting the progression of the infection. The first 41 interventions will be simply the same dry weight dose of each of the 96% food grade ethanolic extracts of each of the 41 different “herbs” listed in Table 2. The first of the next 41 interventions will be extracted from the single herb, Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice). The second intervention will be licorice plus a second herb, according to the priority shown by Roman Numeral in Column 1 of Table 2, such that their total dry weight is equivalent to the dry weight of licorice only in the first intervention. Similarly, the third intervention will be licorice plus the next two more herbs according to the herb’s priority by Roman Numeral as indicated in the first column of Table 2. Successive interventions will include the herbs from the previous intervention plus one more, until in the 41st intervention, all 41 herbs will be present. The quantities of each herb in each intervention will be mathematically “weighted” to reflect their percentages in the complete 41 herb formula. Finally, a second 41 herb formula intervention, namely the aged, not the fresh, solution, will be tested (now nearly two years old) to assess possible difference in safety (intactness of the cellular hosts) and efficacy (weakening of the viral infection) of the aged relative to the freshly made formula. So, the first intervention will include one herb, the second intervention, two herbs, the third, three herbs, until the 41st, containing all 41 herbs has been achieved. Starting with licorice, Glycerrhiza, in the first experiment, additional single “herbs” will be added at each trial, one at a time, according to the Roman Numerals in Column 1 of Table 2. A 42nd intervention will employ the aged, not the fresh, 41 “herb” combination.

The hypothesis challenges the classical wisdom that “you can’t have your synergy and efficacy too” [40], as one author put it, because as you continue to add new herbs to the mix, you dilute the amounts of each herb, pushing the individual herbs into sub-effective doses. In other words, more is less, that is, more herbs means less of each. In the alternative and complementary view, more is more, because even though the amount of each herb will be less, the sum of all the herbs results in a greater, i.e., a synergistic effect.

The question of the impact of aging on the formula’s antiviral potency also goes against conventional wisdom which believes that the fresher the drug, i.e., that the closer it is to its date of production, the better, and the more potent it will be. The hypothesis that aging could improve the product may seem counterintuitive.

However, in either case, that of increasing the N, the number of herbs in a formula, or its aging, what number of herbs, or how long an aging, is optimum? When does synergy start, when does it peak, and when does it decline, and finally when does it become extinguished? These are all questions which the results of the proposed trial will possibly begin to answer, while illuminating pathways for further investigations. Practical applications for a safe and effective combination of herbal tinctures would include both internal and external uses, the latter for sterilizing sprays and for impregnating face masks.

ESL is solely responsible for all the work leading to and resulting in this paper, including researching and writing the paper, editing the paper, wildcrafting or purchasing the herbs, extracting the herbs and medicinal mushrooms, combining the extracts.

Not applicable.

The author acknowledges the help of Shelly Shen-Aridor of the University of Haifa Library for her expert, tireless, and generous assistance in locating and obtaining obscure references. Zipora Lansky drew, in pen and ink, the original artwork in Fig. 1.

This research received no external funding.

The author will provide the composition gratis to fellow researchers via academic collaborations for furthering experimental in vitro or in vivo investigations. The author declares no legal, financial, or institutional conflicts of interest.