1 Department of Medicine, BronxCare Health System, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

2 Department of Medicine, University of Medical Sciences and Technology (UMST), 12810 Khartoum, Sudan

3 Department of Medicine, Salaam Clinic, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

4 Department of Radiology, Texas Medical Center Memorial Hermann Hospital, Houston, TX 77030, USA

5 American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine, Cupecoy, Sint Maarten

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most prevalent sustained cardiac arrhythmia, is intricately linked with atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation (AFTR), a condition distinguished from ventricular functional tricuspid regurgitation by its unique pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications. This review article delves into the multifaceted aspects of AFTR, exploring its epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation, and management strategies. Further, we elucidate the mechanisms underlying AFTR, including tricuspid annular dilatation, right atrial enlargement, and dysfunction, which collectively contribute to the development of tricuspid regurgitation in the absence of significant pulmonary hypertension or left-sided heart disease. The section on diagnostic evaluation highlights the pivotal role of echocardiography, supplemented by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging and computed tomography (CT), in assessing disease severity and guiding treatment decisions. Management strategies for AFTR are explored, ranging from medical therapy and rhythm control to surgical and percutaneous interventions, underscoring the importance of a tailored, multidisciplinary approach. Furthermore, the article identifies gaps in current knowledge and proposes future research directions to enhance our understanding and management of AFTR. By providing a comprehensive overview of AFTR, this review aims to raise awareness among healthcare professionals and stimulate further research to improve patient care and outcomes in this increasingly recognized condition.

Keywords

- atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation

- atrial fibrillation

- right atrial remodeling

- tricuspid annular dilatation

- leaflet tethering

- right ventricular function

- surgical tricuspid valve repair

- transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions

- tricuspid valve replacement

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, affecting millions of people worldwide [1]. AF is associated with various cardiovascular complications, including stroke, heart failure, and valvular heart disease [2]. Recently, there has been growing recognition of the link between AF and isolated tricuspid regurgitation (TR), particularly atrial functional TR (AFTR) [3, 4].

AFTR differs from ventricular functional TR (VFTR), with different pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications [3, 5]. Secondary (or functional) TR results from the deformation of the tricuspid valve complex with morphologically normal leaflets. Moreover, secondary TR is mainly associated with right ventricular dilatation and/or dysfunction, annular dilatation, and/or leaflet tethering. These issues are usually secondary to left-sided valvular heart disease (especially affecting the mitral valve), atrial fibrillation, or pulmonary hypertension [6]. AFTR is characterized by TR secondary to right atrial enlargement and atrial cardiopathy, without significant pulmonary hypertension or left-sided heart disease [3, 7]. Despite its increasing prevalence and prognostic significance, AFTR remains an underappreciated and understudied condition [8, 9].

The prevalence of AF is increasing due to the aging population and improved life expectancy with chronic diseases [10]. In AFTR, TR is a surrogate marker of atrial cardiopathy, which precedes AF [11]. The natural history of TR and right heart chamber remodeling in patients with AF has been poorly assessed; however, restoring sinus rhythm appears beneficial for reducing TR severity and promoting reverse remodeling [12].

This review article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of AFTR, focusing on its pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation, and management strategies. We discuss its epidemiology, association with AF, and impact on outcomes, highlighting key echocardiographic findings. We also address management in specific populations and summarize current treatment options, identifying gaps in understanding and proposing future research directions to enhance patient care.

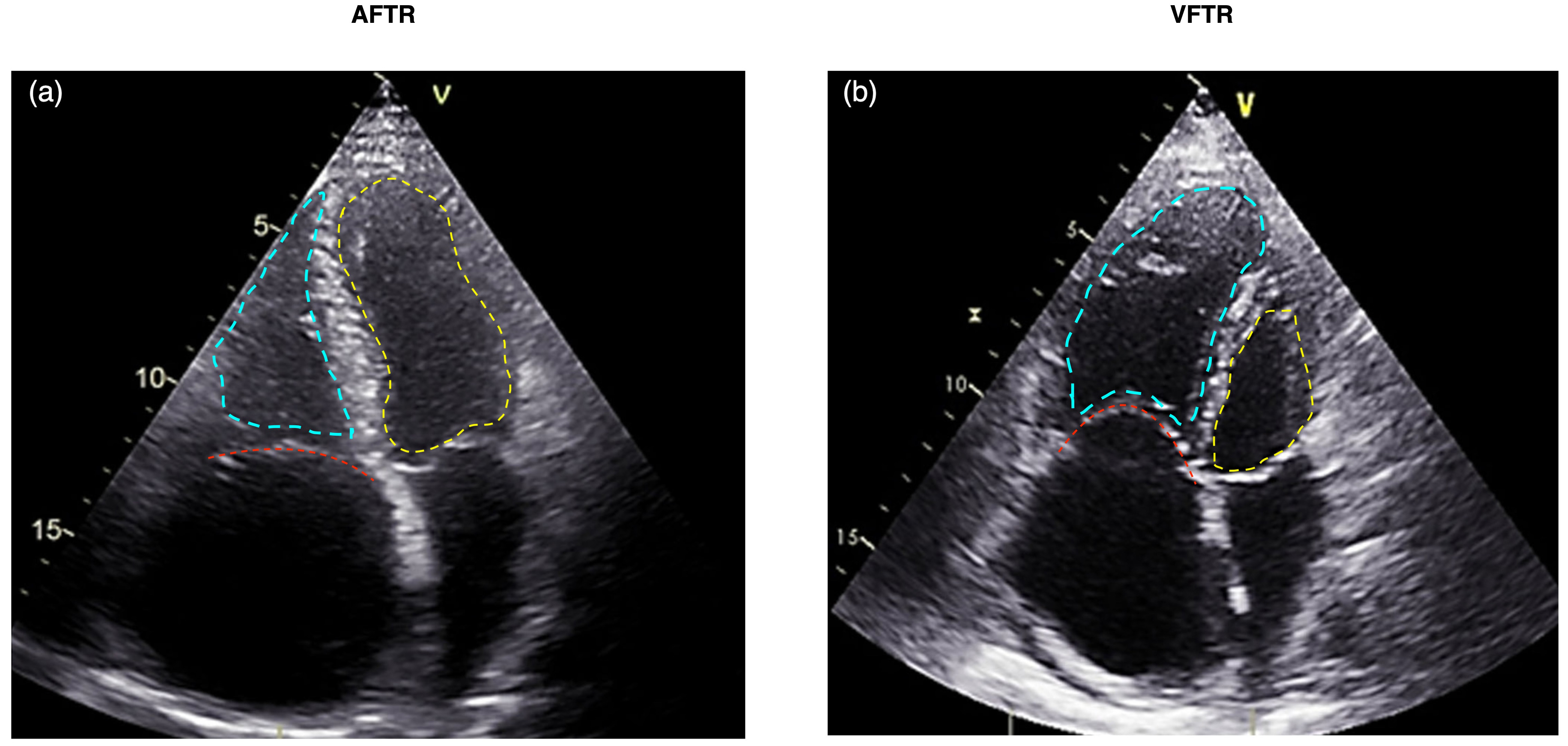

AF is a common arrhythmia that can lead to various cardiovascular complications, including AFTR [3]. Indeed, AFTR is a distinct entity from VFTR (Fig. 1), with different pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications [3].

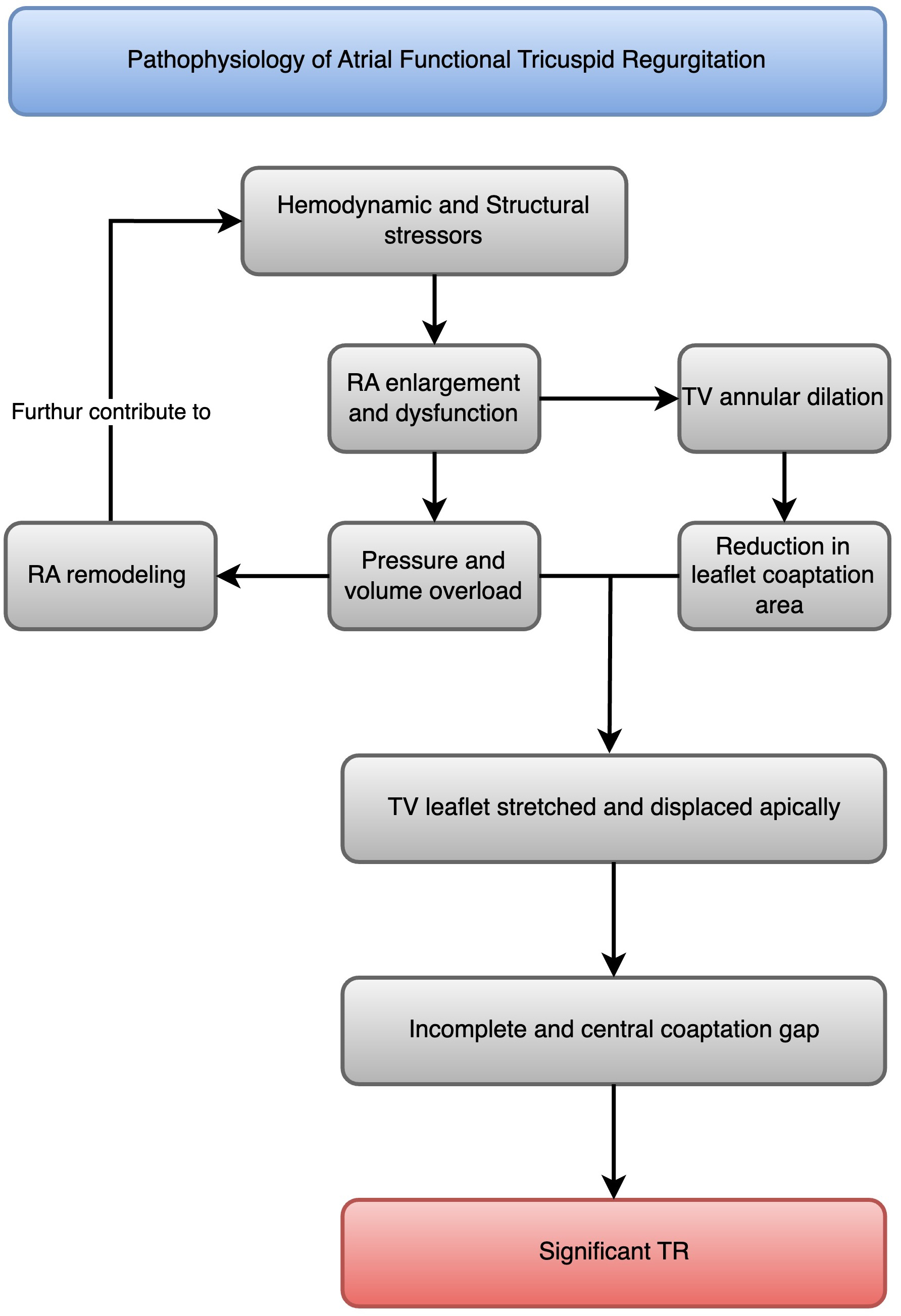

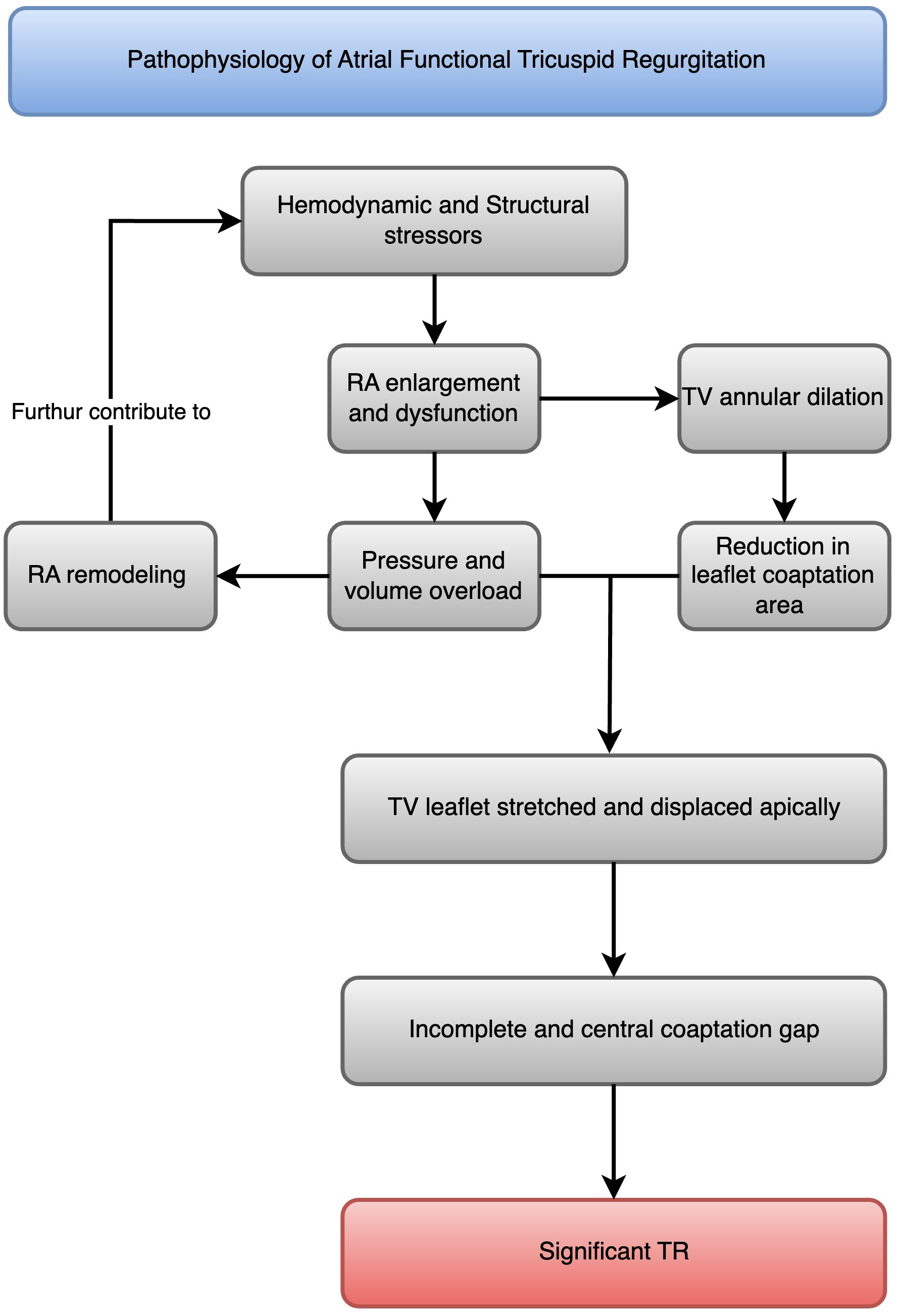

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Pathophysiology of atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation. A flowchart that illustrates the progression from atrial fibrillation to right atrial enlargement and dysfunction, which leads to tricuspid annular dilatation, TV leaflet tethering, malcoaptation, and atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation (AFTR). RA, right atrial; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; TV, tricuspid valve.

In patients with AF, the right atrium undergoes progressive enlargement and dysfunction due to irregular and rapid electrical activity [13]. The structural changes in atrial myocytes caused by AF include (1) an increase in cell size, (2) accumulation of glycogen around the cell nucleus, (3) loss of sarcomeres in the center of the cell, (4) changes in connexin expression, (5) alterations in mitochondrial shape, (6) fragmentation of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, (7) even spread of nuclear chromatin, and (8) changes in the quantity and location of structural cellular proteins [14]. The most noticeable change is the enlargement of atrial cells along with myolysis and the buildup of glycogen around the cell nucleus [14]. These alterations affect atrial contractility and compliance, leading to atrial dilatation [14]. The right atrial remodeling process is characterized by increased collagen deposition, fibrosis, and loss of atrial muscle mass, further contributing to atrial dysfunction [15].

Tricuspid annular dilatation is a key mechanism of AFTR [16]. The tricuspid annulus is a complex, saddle-shaped structure that becomes more planar and circular in patients with AF [17]. This geometric change reduces the leaflet coaptation area and leads to TR [18]. Studies have shown that tricuspid annular diameter is significantly larger in patients with AFTR than those with VFTR [4].

Leaflet tethering and malcoaptation result from AFTR due to atrial dilatation [19]. Furthermore, leaflet tethering and malcoaptation are increasingly observed in VFTR [19]. As the right atrium enlarges and the tricuspid annulus dilates, the tricuspid leaflets stretch and displace apically, leading to incomplete coaptation [20]. This results in a central coaptation gap and significant TR [21].

While AFTR is primarily driven by right atrial enlargement and dysfunction, VFTR is caused by right ventricular dilatation and dysfunction secondary to left-sided heart disease or pulmonary hypertension [20]. In VFTR, the right ventricle undergoes remodeling and becomes more spherical, leading to tricuspid annular dilatation and leaflet tethering [22]. The right atrium may also enlarge in VFTR, but it is usually a consequence rather than a cause of TR [22].

The distinction between AFTR and VFTR has important clinical implications (Fig. 2) [21]. Patients with AFTR may have a better prognosis than those with VFTR, as the right ventricle is often preserved in AFTR [23]. However, AFTR is associated with increased morbidity and mortality compared to patients without TR [24]. The management strategies for AFTR and VFTR may also differ, with a greater emphasis on rhythm control and right atrial volume reduction in AFTR [3]. Leaflet tethering of more than 10 mm (measured in A4C) is a distinct feature of VFTR [25]. The comparison between AFTR and VFTR is presented in Table 1 (Ref. [3, 20, 21, 22, 25]).

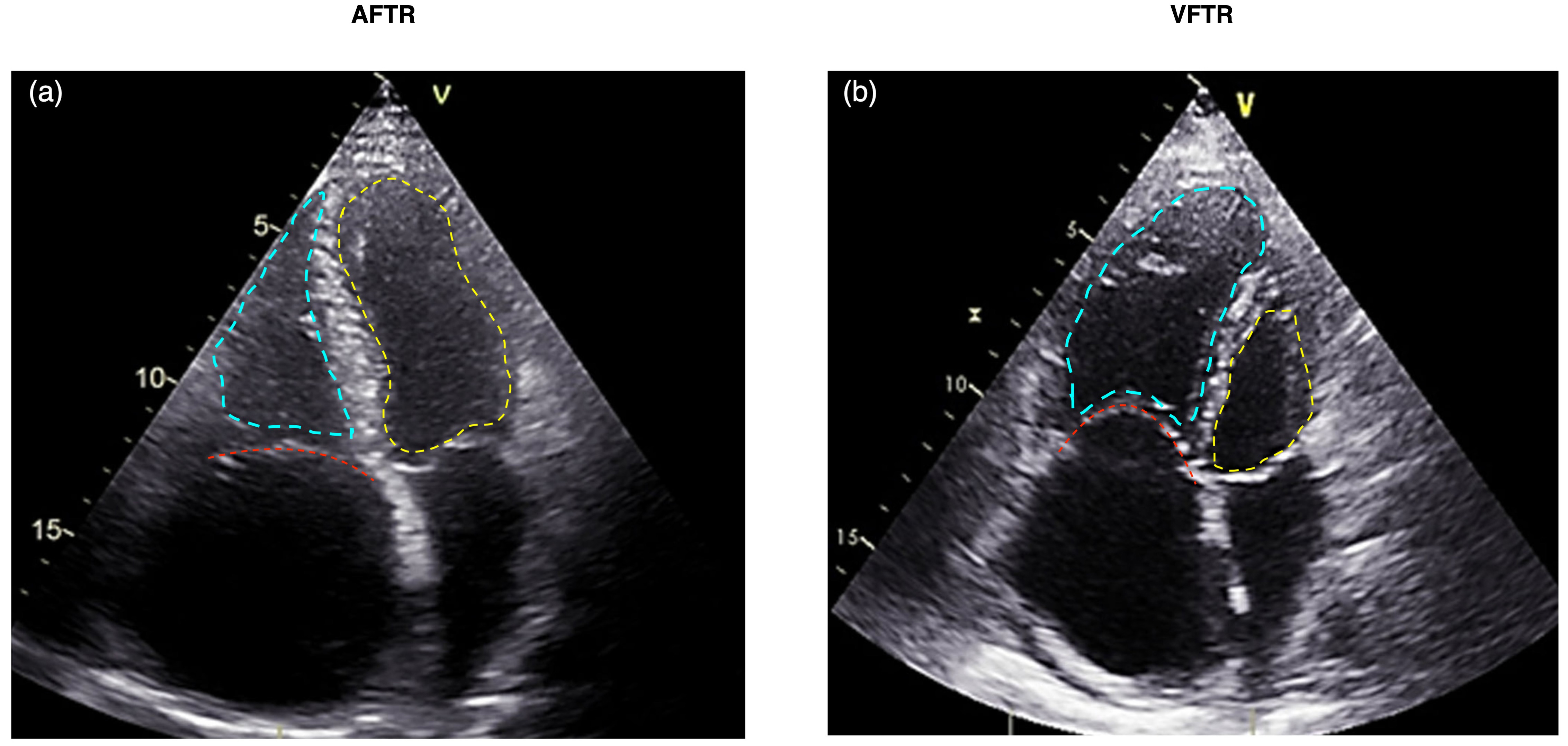

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Echocardiographic comparison of AFTR (a) versus VFTR (b). The tricuspid valve is highlighted with a red dashed line, the left ventricle with a yellow dashed line, and the right ventricle with a blue dashed line. (a) Displays AFTR characterized by annular dilatation due to right atrial enlargement, absence of tethering, and a triangular-shaped right ventricle. (b) Illustrates VFTR with a dysfunctional right ventricle where the basal RV diameter exceeds the annular dilatation. AFTR, atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation; VFTR, ventricular functional tricuspid regurgitation; RV, right ventricle.

| Feature | AFTR | VFTR |

| Pathophysiology | Right atrial enlargement and dysfunction | Right ventricular dilatation and dysfunction |

| Common causes | Persistent/permanent atrial fibrillation [20, 21] | Left-sided heart disease, pulmonary hypertension [21, 22] |

| Diagnostic criteria | Tricuspid annular dilatation, right atrial area enlargement, absence of significant pulmonary hypertension, or left-sided heart disease [20] | Right ventricular dilatation, evidence of pulmonary hypertension, or left-sided heart disease [21] |

| Leaflet tethering ( |

Absent [25] | Present [25] |

| Management strategies | Rhythm control, diuretics, transcatheter interventions [3] | Surgical repair/replacement, transcatheter interventions, management of underlying cause [3] |

| Prognosis | Variable, depends on successful management of atrial fibrillation and right atrial size reduction [25] | Generally poorer due to underlying heart disease [25] |

AF is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, with a global prevalence of 33.5 million individuals [1]. The prevalence of AFTR in the general population is not well-established, as AFTR is often underdiagnosed and underreported, yet it has been noted that the prevalence of AFTR increases with age and is more common in women than in men [8]. However, studies have shown that the prevalence of TR in patients with AF ranges from 25% to 50% [10]. Moreover, in a community-based study, moderate or severe TR prevalence in patients with AF was 6.5% [26].

There is a strong association between AF and TR severity [10]. Patients with AF have a higher TR prevalence and severity compared to those without AF [8]. In a study by Abe et al. [12], the prevalence of moderate or severe TR was significantly higher in patients with AF (25.8%) compared to those with sinus rhythm (15.5%). The severity of TR also correlates with the duration and burden of AF [10]. Patients with persistent or permanent AF have a higher prevalence of severe TR compared to those with paroxysmal AF [8].

AFTR is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [8]. Patients with AFTR have a higher risk of heart failure, stroke, and all-cause mortality compared to those without TR; this is mainly due to more pronounced atrial cardiopathy in the later stages of TR [24]. Research by Benfari et al. [27] found that the presence of severe TR was associated with a 2-fold increased risk of mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction [21]. The impact of AFTR on mortality is independent of other risk factors, such as age, sex, and left ventricular function [8].

While echocardiographic and clinical parameters are essential for diagnosing and monitoring AFTR, patient-centered outcomes such as quality of life and functional status are equally important in assessing the impact of the disease and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

Several studies have demonstrated that AFTR is associated with significant impairments in quality of life and functional capacity. In a study by Topilsky et al. [8], patients with severe TR reported worse scores on the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) compared to those with mild or moderate TR. Similarly, Santoro et al. [9] found that patients with severe TR had significantly lower scores on the Short Form-36 (SF-36) questionnaire, indicating reduced physical and mental well-being.

As assessed by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification or 6-minute

walk test (6MWT), functional status is also impaired in patients with AFTR. In a

study by Mehr et al. [28], 92% of patients with severe TR were in NYHA

class III or IV at baseline, and the mean 6MWT distance was 239

The natural history of TR and right heart chamber remodeling in patients with AF is not well-defined [7]. However, studies have shown that TR severity tends to progress over time in patients with AF [29]. In a study by Utsunomiya et al. [3], the prevalence of severe TR increased from 11% at baseline to 25% after a mean follow-up of 32 months in patients with AF. The progression of TR is associated with ongoing right atrial and ventricular remodeling, characterized by chamber enlargement, dysfunction, and fibrosis [7]. Restoring sinus rhythm through cardioversion or ablation may reduce TR severity and reverse remodeling of the right heart chambers [12].

Accurate diagnosis and assessment of AFTR are crucial for guiding management strategies and predicting patient outcomes. Echocardiography is the primary imaging modality for evaluating AFTR, while other techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and computed tomography (CT), can provide complementary information [30]. The key echocardiographic parameters used to assess the severity of AFTR and the cut-off values are presented in Table 2 (Ref. [31, 32]).

| Grades of TR severity | VC [31, 32] | EROA [31, 32] | R vol. [31, 32] |

| Mild | 3 mm | - | |

| Moderate | 4.0–6.9 mm | - | - |

| Severe | - | - | |

| Massive | 14–20 mm | 60–79 mm2 | 60–74 mL |

| Torrential |

Note: This table summarizes the key echocardiographic parameters used to determine AFTR severity and the cut-off values. Abbreviation: VC, vena contracta; EROA, effective regurgitant orifice area; R vol., regurgitant volume; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; AFTR, atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation.

Echocardiography is the cornerstone of AFTR diagnosis and assessment [28] since it allows for evaluating tricuspid valve morphology, right heart chamber sizes, and the severity of TR. The following key parameters should be assessed during the echocardiographic evaluation of AFTR.

4.1.1.1 Grades of TR

Mild TR is defined by an effective regurgitant orifice area (EROA) of

4.1.1.2 Tricuspid Annular Diameter

Tricuspid annular dilatation is a hallmark of AFTR [4]. The normal tricuspid

annular diameter in adults is 28–35 mm, and values

4.1.1.3 Right Atrial Area

Right atrial enlargement is a key AFTR feature associated with TR severity [3].

The right atrial area should be measured in the apical 4-chamber view at

end-systole, tracing the right atrial endocardial border [30]. A right atrial

area

4.1.1.4 Right Ventricular Free Wall Longitudinal Strain

Right ventricle (RV) free wall longitudinal strain (RVFWLS) is a sensitive marker of RV

dysfunction and can be assessed using speckle-tracking echocardiography [33].

Reduced RVFWLS (fewer negative values) is associated with more severe TR and

worse outcomes [36]. In a study by Prihadi et al. [7], patients with

severe TR had significantly lower RVFWLS than those with mild or moderate TR

(–15

Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography provides unique insights into the complex geometry of the tricuspid valve and right heart chambers in patients with AFTR [37]. Three-dimensional echocardiography allows a more accurate assessment of tricuspid annular size, leaflet morphology, and coaptation defects compared to 2D echocardiography [16]. In a study by Ton-Nu et al. [16], 3D echocardiography demonstrated that patients with functional TR had larger tricuspid annular areas, more planar annular shapes, and greater tethering distances than controls. Indeed, 3D echocardiography can also guide interventional procedures for AFTR, such as transcatheter tricuspid valve repair [38].

CMR is a valuable tool for assessing right heart chamber sizes, function, and flow dynamics in patients with AFTR [39, 40]. CMR is considered a gold-standard tool for assessing TR severity and provides a high spatial resolution that can accurately quantify RV volumes and ejection fraction [40]. In a study by Hahn et al. [41], CMR-derived RV end-diastolic volume and ejection fraction were independent predictors of mortality in patients with severe TR. CMR can also visualize the tricuspid valve apparatus and identify structural abnormalities [40].

CT can provide detailed anatomical information about the tricuspid valve and right heart chambers in patients with AFTR [42, 43]. CT allows for precise measurement of tricuspid annular dimensions, leaflet morphology, and relationship with surrounding structures [43]. This information can be particularly useful for planning surgical or transcatheter interventions for AFTR [42]. In a study by Hinzpeter et al. [42], CT-derived tricuspid annular dimensions and leaflet angles predicted procedural success and outcomes after transcatheter tricuspid valve repair.

AFTR can occur in various clinical settings and patient populations. Thus, understanding the prevalence, mechanisms, and clinical implications of AFTR in these specific groups is essential for tailoring management strategies and improving patient outcomes.

Atrial septal defects (ASDs) are associated with an increased prevalence of AFTR [38]. The left-to-right shunt in ASDs leads to right atrial and ventricular volume overload, which can cause tricuspid annular dilatation and leaflet tethering [44]. In a study by Toyono et al. [44], the prevalence of moderate or severe TR in patients with ASDs and chronic AF was significantly higher than in those with ASDs and sinus rhythm. The underlying pathomechanism of TR in ASD patients is complex and involves several factors. The left-to-right shunt increases right heart preload, leading to right atrial and ventricular enlargement. Chronic shunting can lead to pulmonary hypertension, further exacerbating right ventricular dilatation and tricuspid annular enlargement.

The presence of AF in ASD patients can worsen atrial remodeling and contribute to tricuspid annular dilatation. Interestingly, ASD closure can lead to a sudden reduction in right heart preload [45]. This abrupt change in hemodynamics can unmask pre-existing TR or even worsen it in some cases. The mechanism involves reduced right ventricular filling, potentially leading to geometric changes that affect tricuspid valve coaptation, altered right atrial and ventricular compliance due to sudden volume reduction, and possible right ventricular dysfunction in patients with longstanding volume overload [45]. The presence of AFTR in patients with ASDs is associated with worse functional capacity and increased mortality. Surgical or transcatheter closure of ASDs can reduce TR severity and improve right heart chamber sizes and function in many cases. However, persistent AF after ASD closure may limit the reversibility of AFTR and warrant concomitant tricuspid valve intervention [38].

AFTR is a common complication after cardiac transplantation, with a reported prevalence of 20–50% [46]. The mechanisms of AFTR in this setting include donor–recipient size mismatch, right ventricular dysfunction, and biatrial anastomosis technique [47]. Biatrial anastomosis, which involves suturing the atria of the donor and recipient together, can lead to atrial enlargement and distorting of the tricuspid valve apparatus [48]. In a study by Wartig et al. [46], patients with biatrial anastomosis had a significantly higher prevalence of moderate or severe TR compared to those with bicaval anastomosis (45% vs. 15%); TR occurs due to structural changes in the atrial chambers. The presence of AFTR after cardiac transplantation is associated with reduced exercise capacity, right ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality [46]. Management strategies for AFTR in this population include diuretics, pulmonary vasodilators, and tricuspid valve intervention in selected cases [47].

AFTR can develop or worsen after left-sided valve surgery, particularly in patients with pre-existing AF [49]. The mechanisms of AFTR in this setting include right ventricular dysfunction due to cardiopulmonary bypass, pericardial constraint, and progression of underlying atrial and valvular disease [50]. In a study by Dreyfus et al. [50], the prevalence of moderate or severe TR increased from 27% preoperatively to 68% at 5 years after mitral valve surgery in patients with pre-existing AF. The presence of AFTR after left-sided valve surgery is associated with reduced functional capacity, right ventricular dysfunction, and increased mortality [51]. Management strategies for AFTR in this population include aggressive treatment of AF, optimization of medical therapy, and consideration of concomitant or staged tricuspid valve intervention [52, 53, 54, 55, 56]. In a study by Chikwe et al. [52], concomitant tricuspid valve repair during left-sided valve surgery was associated with improved long-term survival and reduced TR progression compared to left-sided valve surgery alone.

Managing AFTR is challenging and requires a multidisciplinary approach tailored to the individual patient. Treatment options include medical therapy, surgical interventions, and percutaneous procedures. The choice of intervention depends on various factors, including TR severity, underlying cardiac conditions, patient characteristics, and institutional expertise [57]. The indications, advantages, disadvantages, and outcomes of surgical and percutaneous interventions for AFTR are presented in Table 3 (Ref. [58, 59, 60, 61, 62]).

| Characteristic | Surgical interventions | Percutaneous procedures |

| Indications | Concomitant left-sided valve disease and acceptable surgical risk [58] | High surgical risk, isolated TR, and prior cardiac surgery [61] |

| Advantages | Definitive repair or replacement and concomitant procedures possible [59] | Less invasive and shorter recovery time [62] |

| Disadvantages | Higher perioperative risk and longer recovery time [60] | Limited long-term data and a potential need for reintervention [62] |

| Outcomes | Improved symptoms and survival, but significant morbidity and mortality [60] | Promising early results [62], but long-term durability unknown |

Note: This table compares the indications, advantages, disadvantages, and outcomes of surgical and percutaneous interventions for AFTR. Abbreviation: TR, tricuspid regurgitation; AFTR, atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation.

Diuretics and salt restriction are the mainstay of medical therapy for patients with AFTR and right heart failure symptoms [57]. Loop diuretics, such as furosemide, can help reduce peripheral edema and improve functional capacity [63]. However, aggressive diuresis may lead to renal dysfunction and electrolyte abnormalities, requiring careful monitoring [63].

Rhythm control strategies, including antiarrhythmic drugs and catheter ablation, may benefit patients with AFTR [12]. Restoration and maintenance of sinus rhythm can improve right atrial and ventricular function, potentially reducing TR severity [12]. In a study by Abe et al. [12], successful catheter ablation for AF was associated with a significant reduction in TR severity and improvement in right ventricular function. A study by Soulat-Dufour et al. [64] found that actively restoring sinus rhythm (SR) by cardioversion and/or ablation is connected with reduced functional atrioventricular regurgitation.

Current guidelines recommend concomitant tricuspid valve repair for patients

with severe TR (stages C and D) undergoing left-sided valve surgery [58].

However, there is growing evidence to support earlier intervention in patients

with moderate TR (stage B) and tricuspid annular dilation (

Surgical techniques for AFTR include tricuspid valve repair (annuloplasty) and replacement. Ring annuloplasty is preferred for suitable valve morphology, offering lower operative mortality and better long-term outcomes than replacements [59]. A meta-analysis by Veen et al. [49] showed ring annuloplasty associated with lower recurrent TR risk and improved survival versus suture annuloplasty. However, for tricuspid valve replacement, a recent meta-analysis by Scotti et al. [60] revealed relatively poor outcomes, with 12% operative mortality and frequent complications. Long-term outcomes for bioprosthetic TVR showed incidence rates of 6 per 100 person-years for death and 8 per 100 person-years for significant TR recurrence. Notably, this analysis did not differentiate between AFTR and VFTR, highlighting the need for future studies to address this distinction [60]. In a study by Gammie et al. [65], it was found that adding concomitant tricuspid annuloplasty (TA) during mitral valve repair (MVR) reduced the rate of treatment failure at 2 years compared to MVR alone. Treatment failure was defined as the composite of death, re-operation for tricuspid regurgitation, progression of TR by two grades from baseline, or the presence of severe TR at 2 years [65]. However, this reduction in TR progression was associated with a higher risk of permanent pacemaker implantation [65].

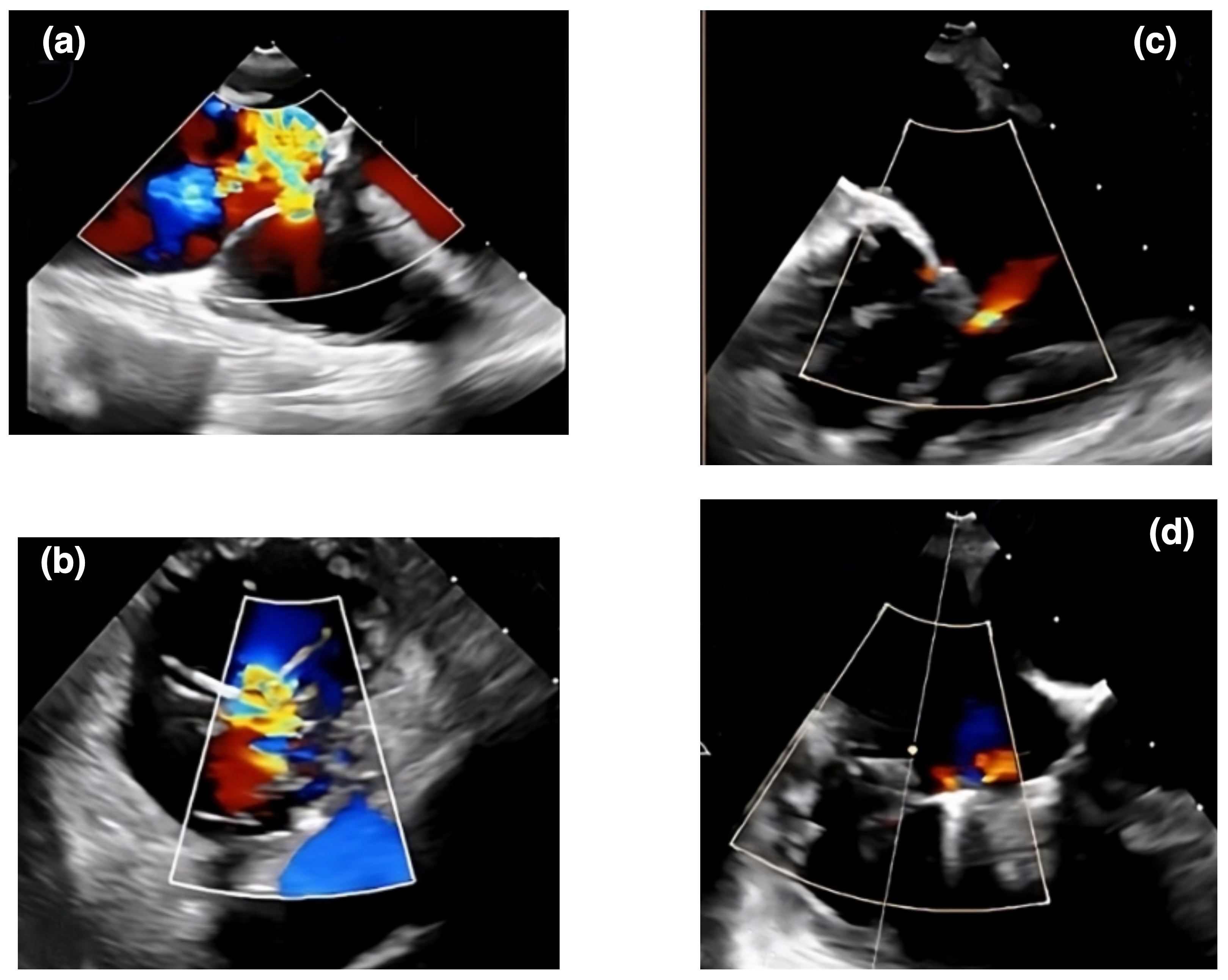

Transcatheter edge-to-edge repair using the MitraClip system (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, CA, USA) has emerged as a promising treatment option for patients with AFTR at high surgical risk [66]. The TRILUMINATE trial demonstrated significant improvements in TR grade, functional status, and quality of life 1 year after the procedure [67]. However, the long-term durability and impact on clinical outcomes remain to be established. In a propensity-matched analysis by Taramasso et al. [66], transcatheter edge-to-edge repair was associated with similar improvements in TR severity and functional status compared to medical therapy but with a higher rate of major adverse events. To accurately assess the severity and mechanisms of tricuspid regurgitation, it is crucial to employ detailed transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiograms to evaluate the tricuspid valve anatomy and effectively guide patient selection for transcatheter edge-to-edge repair [68]. For tricuspid transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (T-TEER), the TriClip and PASCAL systems are designated therapies with specific features (Fig. 3). TriClip uses a right heart-specific guide and delivery system, available in various clip sizes with independent gripper action and an active locking mechanism [69]. PASCAL offers high maneuverability and independent leaflet capture capability [70]. Both systems have received regulatory approval and are used to treat severe tricuspid regurgitation. Off-label usage of the MitraClip system for tricuspid repair should only be considered in countries where both TriClip and PASCAL are unavailable, ensuring focus on devices specifically designed for tricuspid valve intervention [71]. Future studies should continue to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and durability of these technologies compared to surgical and medical therapies [5, 57].

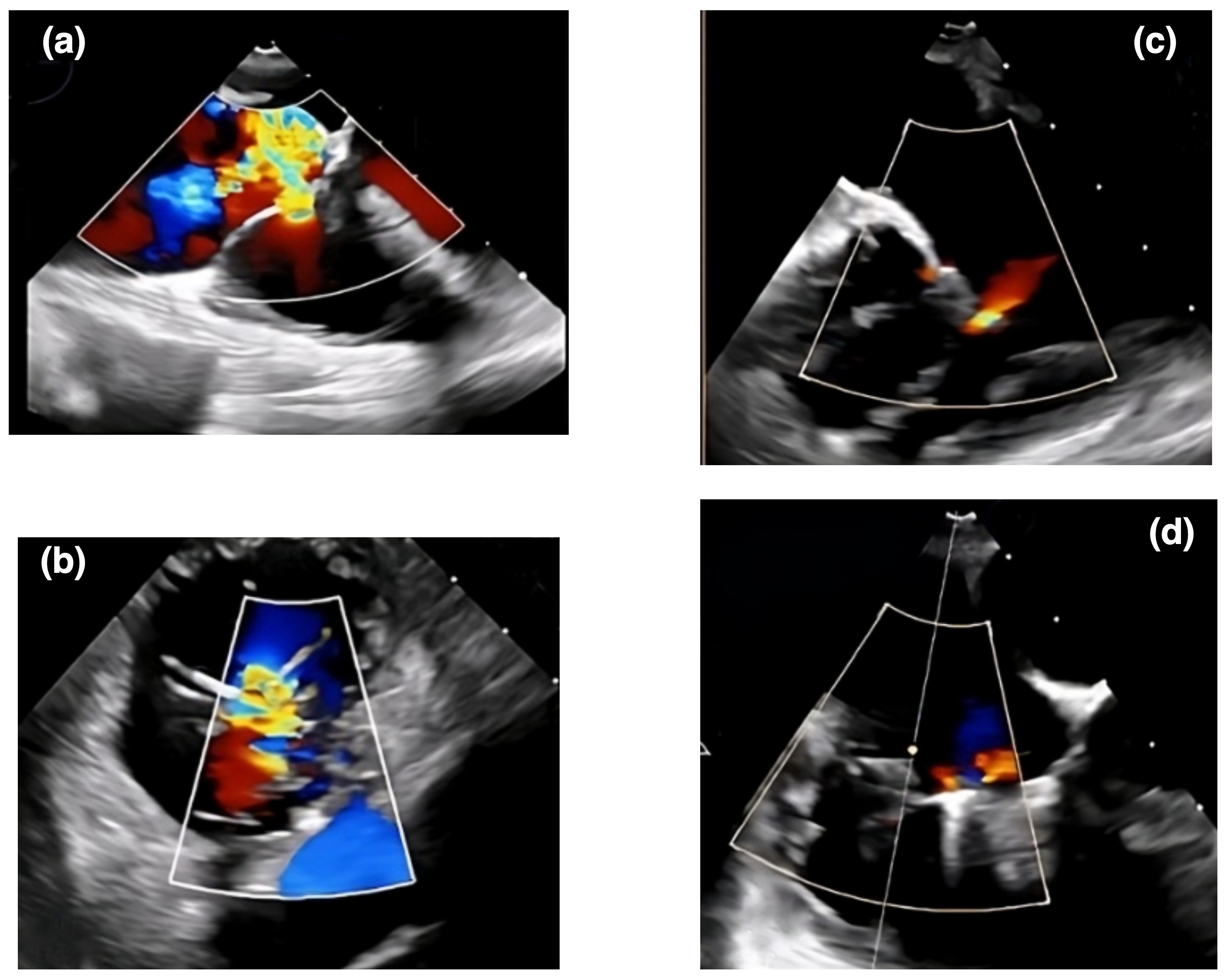

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

An echocardiographic representation of a transcatheter therapy outcome using the TriClip system for AFTR. Panels (a) and (b) show Doppler echocardiographic images of tricuspid regurgitation before a TriClip intervention. Panels (c) and (d) display echocardiographic views of tricuspid regurgitation after the TriClip intervention. AFTR, atrial functional tricuspid regurgitation.

Transcatheter tricuspid valve replacement (TTVR) is an emerging technology for

treating AFTR in patients with anatomical challenges or failed previous repairs

[61]. Early feasibility studies have shown promising results, with high

procedural success rates and significant improvements in TR severity and

functional status [61]. The EVOQUE tricuspid valve replacement system (Edwards

Lifesciences) has advanced beyond early feasibility studies and received approval

in 2022, making it available for clinical use in Europe. A study by Webb

et al. [72] reported favorable 1-year outcomes using the EVOQUE system,

including a high technical success rate, significant reduction in TR severity,

and improved functional status. At 1 year, 96% of patients had TR grade

Transcatheter annuloplasty (Cardioband), orthotopic, and heterotopic valve replacement are preferred methods for treating patients with AFTR due to their association with lower operative mortality and better long-term outcomes [62]. These procedures rely on crucial pre-procedure imaging techniques, such as cardiac computed tomography (CCT) and vascular computed tomography angiography (CTA), which provide meticulous anatomical assessments and accurate evaluations of annular size [62, 74]. Specifically, cardiac computed tomography angiography (CCTA) is used before transcatheter annuloplasty (Cardioband) to assess the structural and size characteristics of the tricuspid annulus [75]. CCTA also evaluates the distance from coronary vessels, the catheter’s insertion, the expected angle from the inferior vena cava to the right atrium, and its alignment with the tricuspid annulus. Additionally, CCTA provides the necessary angulations for fluoroscopy during implantation [75]. Several devices are available in clinical practice, including coaptation devices and annuloplasty systems, such as the Cardioband and heterotopic valve implantation techniques; however, newer generations and innovative technologies are in development [76, 77]. The Cardioband Tricuspid System is specifically designed to reduce the size of the tricuspid annulus, improving leaflet coaptation and reducing regurgitation [69].

Comparative studies of surgical and percutaneous interventions for AFTR are limited, and the optimal treatment strategy remains unclear. In a meta-analysis by Veen et al. [49], surgical tricuspid valve repair was associated with lower rates of recurrent TR and improved survival compared to percutaneous interventions. However, this analysis included mostly observational studies and was limited by heterogeneity in patient populations and treatment techniques.

Recent comparative studies have provided valuable insights into the outcomes of transcatheter tricuspid valve interventions in AFTR and VFTR patients. A study by Russo et al. [78] compared outcomes of T-TEER in AFTR and VFTR patients, finding similar procedural outcomes for both groups, with differences in mortality primarily attributed to underlying diseases. For transcatheter annuloplasty, Barbieri et al. [79] compared the procedural success of the Cardioband device in AFTR and VFTR patients, finding no significant differences between groups in annulus diameter reduction, vena contracta reduction, or effective regurgitation orifice area reduction. Improvement in TR severity of at least two grades was similar in both groups (90.0% in VFTR vs. 91.4% in AFTR) [79]. These studies demonstrate that both T-TEER and transcatheter annuloplasty can effectively treat both forms of functional TR with similar procedural success rates. Furthermore, they highlight that differences in long-term outcomes may be more related to underlying cardiac conditions than the type of functional TR.

Patients with AFTR demonstrated significantly better long-term survival than

those with VFTR. The 10-year cumulative survival rate for AFTR was 78%, whereas

it was 46% for VFTR (p

Despite the growing recognition of AFTR as a distinct entity with significant clinical implications, several gaps in our understanding of this condition still need to be addressed. Thus, future research efforts should address these knowledge gaps and explore novel therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes.

One of the major limitations in our current understanding of AFTR is the lack of standardized diagnostic criteria and severity grading [57]. The current guidelines for assessing TR severity were developed primarily for patients with left-sided heart disease and may not accurately reflect the unique pathophysiology of AFTR [28, 30]. Future studies should aim to establish specific diagnostic criteria and severity grading systems for AFTR, considering the complex interplay between atrial and right ventricular remodeling [3, 7].

Another gap in our knowledge is the natural history and prognostic implications of AFTR [8, 21]. While several studies have demonstrated an association between AFTR and adverse outcomes, the long-term trajectory of this condition and its impact on patient survival and quality of life remain poorly defined [8, 9]. Future research should focus on elucidating the natural history of AFTR and identifying prognostic markers to guide risk stratification and treatment decisions [8, 28].

Prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to better characterize the natural history of AFTR and its progression over time [29]. These studies should include patients with varying degrees of AFTR severity and assess the impact of clinical factors, such as AF burden, right ventricular function, and pulmonary hypertension, on the course of the disease [81]. Serial echocardiographic assessments and biomarker measurements could provide valuable insights into the mechanisms and predictors of AFTR progression [3, 28].

There is a lack of data on the optimal management strategies for patients with AFTR [57]. Current treatment approaches are largely extrapolated from studies of patients with left-sided heart disease and may not be directly applicable to the AFTR population [49, 63]. Prospective, randomized trials are needed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of various therapeutic interventions, such as diuretics, pulmonary vasodilators, and rhythm control strategies, in patients with AFTR [63, 82]. These studies should also assess the impact of different management strategies on patient-centered outcomes, such as functional capacity and quality of life [28, 83].

Long-term outcome data are essential for guiding clinical decision-making and patient counseling in the setting of AFTR [8, 22]. Prospective studies with extended follow-up periods are needed to evaluate the impact of AFTR on patient survival, cardiovascular events, and healthcare utilization [29, 84]. These studies should also assess the long-term durability and effectiveness of various therapeutic interventions, such as transcatheter tricuspid valve repair or replacement [66, 67].

As our understanding of the pathophysiology of AFTR continues to evolve, novel therapeutic targets and interventions may emerge [85]. For example, targeting the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) with pharmacologic agents, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or aldosterone antagonists, may help to attenuate right atrial and ventricular remodeling in patients with AFTR [10]. Similarly, novel antifibrotic therapies, such as pirfenidone or nintedanib, may have a role in preventing or reversing the structural changes associated with AFTR [86].

AFTR is a clinically significant condition with distinct pathophysiology, epidemiology, and management strategies. This review underscores the necessity of accurate diagnosis, timely intervention, and personalized treatment approaches since raising awareness among healthcare professionals is crucial for enhancing patient care and outcomes. Despite advancements, several important gaps in our understanding of AFTR remain, warranting further investigation. Thus, prospective, longitudinal studies are needed to improve the characterization of the natural history, optimal management strategies, and long-term outcomes of this condition. Therefore, randomized controlled trials for each distinct form of TR are essential to establish evidence-based treatment approaches. Moreover, novel therapeutic targets and interventions, such as RAAS inhibition, antifibrotic therapies, and innovative transcatheter devices, should be explored in future research efforts. By addressing these knowledge gaps and advancing the field of AFTR, we can significantly improve the care and outcomes of patients with these increasingly recognized and clinically significant conditions.

MM and AA conceptualized and designed the research study. SA and SS performed the research, contributing significantly to the acquisition of data. AM provided critical insights and advice on the experimental design and methodology, enhancing the study’s overall execution. FOM and SJN played a pivotal role in the analysis and interpretation of the data, ensuring the accuracy and relevance of the findings. MM took the lead in drafting the manuscript, with substantial contributions from AA, SA, SS, AM, FOM, and SJN, who critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors engaged actively in the discussion of results and contributed to the final manuscript, ensuring its integrity and accuracy. Each author has reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript, agreeing to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This work was supported by BronxCare Health System.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.