1 State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Arrhythmia Center, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, 100037 Beijing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: Atrioventricular block (AVB) is thought to be a rare

cardiovascular complication of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), though

limited data are available beyond case reports. We aim to describe the baseline

characteristics, proteomics profile, and outcomes for patients with

COVID-19-related AVB. Methods: We prospectively recruited patients

diagnosed with COVID-19-related AVB between November 2022 and March, 2023.

Inclusion criteria were hospitalization for COVID-19 with the diagnosis of AVB. A

total of 24 patients diagnosed with COVID-19 without AVB were recruited for

control. We analyzed patient characteristics and outcomes and performed a

comparative proteomics analysis on plasma samples of those patients and controls.

Results: A total of 17 patients diagnosed with COVID-19-related AVB and

24 individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 infection without AVB were included. Among

patients with COVID-19-related AVB, the proportion of concurrent pneumonia was

significantly higher than controls (7/17 versus 2/24, p

Keywords

- COVID-19

- atrioventricular block

- comparative proteomics analysis

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused a worldwide pandemic that continues to be relevant globally. Alongside the respiratory system, an arrhythmogenic effect of COVID-19 has been recognized. Tachyarrhythmias such as atrial tachycardia, sinus tachycardia, and ventricular arrhythmias are documented as the most frequent dysrhythmias [1, 2, 3]. Though bradyarrhythmia presenting as atrioventricular block (AVB) and sinus bradycardia are less frequently reported, they are thought to have a worse prognosis [4, 5].

Although increasing amounts of data have reported the incidence of COVID-19-related AVB, however, the clinical characteristics, classification, and outcomes have not been well summarized. Moreover, several hypotheses as cytokine storms, direct viral damage, hypoxia, and immune disorders, have been thought to influence the cardiac conduction system, but the concrete pathogenesis of COVID-19-related AVB remains unknown [6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

In this study, we recruited 17 COVID-19-related AVB patients and summarized their clinical characteristics and outcomes. We hypothesized COVID-19 induces molecular changes that can be detected in the patient’s sera and used mass spectrometry assays for data-independent acquisition to comparatively analyze the proteomics profile of COVID-19-related AVB patients and several control groups.

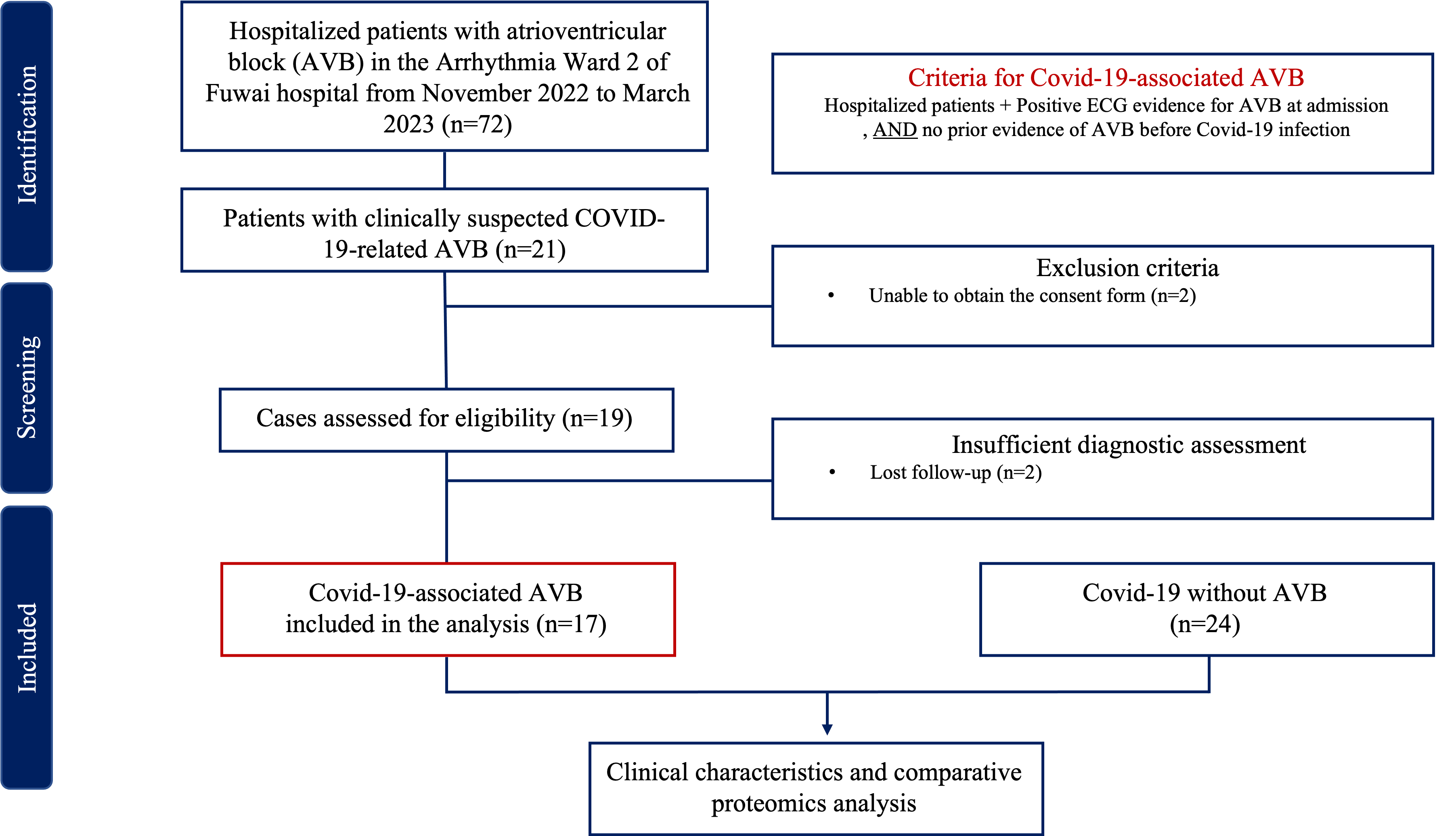

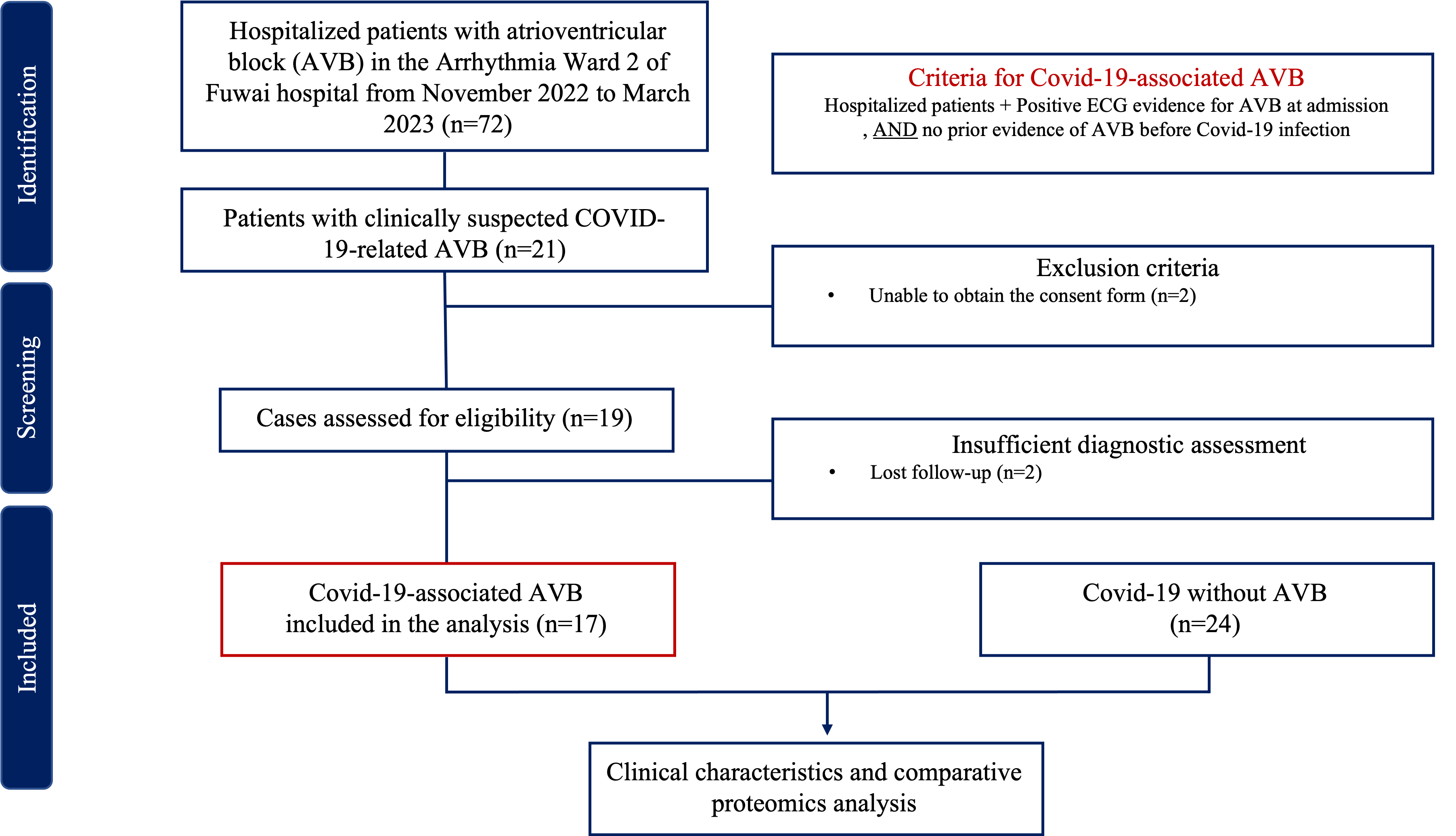

This is a single-center, prospective, observational study. A total of 17 patients diagnosed with COVID-19-related AVB, and 24 individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 without AVB were recruited from November 2022 to March 2023. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in Fig. 1. This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Fuwai Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. We obtained informed consent from all participants. All COVID-19-related AVB patients enrolled in this study have to fulfilled the inclusion criteria: (1) Definite SARS-CoV-2 infection evidenced by positive RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab or rapid antigen detection test. (2) No prior evidence of AVB from resting electrocardiogram and/or ambulatory electrocardiogram before the COVID-19 infection. Among the suspected cases of COVID-19-related AVB, cases were excluded for the following reason: (1) Unable to obtain the consent form.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flow chart of inclusion and exclusion criteria. ECG, electrocardiogram; AVB, atrioventricular block; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Medical history, clinical characteristics, laboratory tests, and outcomes were obtained from in-hospital medical records. A transthoracic echocardiogram was performed according to the latest guidelines. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured by Simpson’s biplane technique. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation included T1 and T2 mapping, late gadolinium enhancement (LGE), and conventional cine. For patients who were in need of a permanent pacemaker, sensed and paced atrioventricular intervals were programmed as 170 and 200 ms at follow-up.

Proteins of serum pools were separated using the Human 14 Multiple Affinity Removal System Column (LOT-51886560, Agilent Technologies, Beijing, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol [11]. The low and high-abundance proteins were collected respectively, desalinated, and concentrated using an ultrafiltration tube. Then we added SDT buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 4% SDS), boiled for 15 min and centrifuged at 14,000 g for 20 min. We used the BCA Protein Assay Kit (LOT-5000001, Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA) to quantify the supernatant. The sample was then stored at –80 °C.

We added the DTT (LOT-161-0404, Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA) to each sample and mixed it.

Iodoaceamide (LOT-163-2109, Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA) was added to block reduced cysteine

residues and then incubated for 30 min in darkness. Next, the samples were

filtrated and washed with 100 µL UA buffer and 100 µL 25 mM

NH

Then each sample was desalted on C18 Cartridges (LOT-Empore™ C18, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), concentrated, and reconstituted in formic acid. The peptide was measured by 280 nm UV light. Calibration peptides were spiked into the sample for DIA experiments.

We used a Q-Exactive HF-X mass spectrometer to analyze each sample by the Easy-nLC 1200 chromatography system in the data-independent acquisition (DIA) mode. Each DIA cycle contained one full MS–SIM scan, and 44 DIA scans covered a mass range of 350–1800 m/z.

The FASTA sequence database was searched with Spectronaut

We use the Anderson-Darling test and Shapiro-Wilk test to evaluate the normality

of continuous variables. Continuous variables that passed the normality test were

reported as mean and standard deviation. Continuous variables that failed the

normality test were recorded as median and quartile 1 (Q1) to quartile 3 (Q3).

The unpaired t-test and Mann-Whitney test were used to analyze the

continuous variables. We use Fisher exact test to compare the categorical

variables. All statistical analyses were two-tailed. p value

Baseline characteristics of all 17 COVID-19-related AVB patients are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 59.9 years old, 29.4% of the patients were female, and all had received a COVID-19 vaccination before the onset of AVB. The diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection was confirmed by a positive RT-PCR nasopharyngeal swab (76.5%) or rapid antigen detection test (82.4%). Eleven (64.7%) patients had intermittent cough, and 13 (76.5%) patients had fever during COVID-19. Noticeably, all 17 patients had palpitation, 8 patients (47.1%) had syncope onset, 5 patients (29.4%) complained of chest pain. Nine patients (52.9%) had permanent AVB, and 8 patients (47.1%) had paroxysmal AVB. Seven patients (41.2%) had AVB with pneumonia. The median length of stay was 7.0 days (Q1–Q3: 6.0–9.0) with a maximum hospital stay of 15 days.

| All | AVB with COVID-19 | COVID-19 without AVB | p value | ||

| Overall | 41 | 17 | 24 | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years, mean |

56.8 |

59.9 |

54.7 |

0.17 | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 14 (34.1) | 5 (29.4) | 9 (37.5) | 0.74 | |

| BMI, kg/m |

24.6 |

23.7 |

25.3 |

0.13 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 14 (34.1) | 11 (64.7) | 3 (12.5) | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (7.3) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.12 | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 4 (9.8) | 4 (23.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.06 | |

| Current or previous smoker, n (%) | 14 (34.1) | 7 (41.2) | 7 (29.2) | 0.51 | |

| Current or previous cancer, n (%) | 3 (7.3) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (4.2) | 0.56 | |

| Autoimmune disorder, n (%) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.41 | |

| PR interval before COVID-19 infection, ms, mean |

135.0 |

141.5 |

135.6 |

0.52 | |

| ECG on admission | |||||

| Third-Degree AVB, n (%) | 14 (34.1) | 14 (82.4) | - | ||

| Permanent AVB, n (%) | 9 (22.0) | 9 (52.9) | - | ||

| Pneumonia on CT scan, n (%) | 9 (22.0) | 7 (41.2) | 2 (8.3) | 0.02* | |

| Laboratory tests on admission | |||||

| WBC, ×10 |

6.0 (4.7–7.3) | 6.8 (5.2–8.9) | 5.7 (4.3–6.9) | 0.01* | |

| Lymphocyte count, ×10 |

1.6 (1.3–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–1.8) | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | 0.09 | |

| hs-cTnI, ng/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.002 (0.002–0.007) | 0.005 (0.003–0.027) | 0.002 (0.002–0.003) | ||

| NT-pro BNP, pg/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 67.5 (20.4–228.0) | 241.0 (122.5–1684.0) | 33.5 (17.8–66.5) | ||

| MYO, ng/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 31.2 (22.6–50.0) | 39.0 (29.4–76.0) | 27.6 (20.4–43.4) | 0.04* | |

| CK-MB, U/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.3) | 1.2 (0.6–1.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.03* | |

| CRP, mg/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 2.6 (1.8–5.0) | 4.8 (2.7–6.7) | 2.0 (1.6–3.4) | ||

| D-dimer, µg/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.3 (0.2–1.2) | 1.2 (0.2–3.7) | 0.2 (0.2–0.3) | ||

| ALT, IU/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 22.0 (15.5–34.0) | 21.0 (14.5–31.5) | 27.0 (15.5–38.5) | 0.28 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (Q1–Q3) | 72.9 (59.8–84.7) | 69.4 (61.4–93.2) | 72.9 (60.8–81.2) | 0.63 | |

| Albumin, g/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 45.0 (39.9–46.4) | 41.9 (38.0–45.3) | 45.5 (44.5–47.6) | ||

| Echocardiography on admission | |||||

| LVEDD, mm, mean |

47.2 |

49.3 |

45.7 |

0.01* | |

| LVEF, %, mean |

64.7 |

63.7 |

65.4 |

0.37 | |

AVB, atrioventricular block; BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; MYO, myoglobulin; CK-MB, MB isoenzyme of creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALT, alanine transaminase; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. * indicates statistically significant; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; SD, standard deviation; ECG, electrocardiogram; CT, computed tomography.

In laboratory tests, the level of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin-I (median

0.005 versus 0.002 ng/mL, p

| All | AVB with COVID-19 | COVID-19 without AVB | p value | ||

| Overall | 19 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Demographics | |||||

| Age, years, mean |

51.0 |

55.7 |

46.8 |

0.26 | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 9 (47.4) | 3 (33.3) | 6 (60.0) | 0.37 | |

| BMI, kg/m |

25.6 |

25.1 |

26.1 |

0.58 | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | 5 (55.6) | 2 (20.0) | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 3 (15.8) | 3 (33.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.09 | |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.47 | |

| Current or previous smoker, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 0.63 | |

| Current or previous cancer, n (%) | 3 (15.8) | 2 (22.2) | 1 (10.0) | 0.58 | |

| Autoimmune disorder, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.47 | |

| ECG on admission | |||||

| Third-Degree AVB, n (%) | 9 (47.4) | 9 (100.0) | - | ||

| Permanent AVB, n (%) | 6 (31.6) | 6 (66.7) | - | ||

| Laboratory tests on admission | |||||

| WBC, ×10 |

6.3 (5.3–7.4) | 7.4 (5.2–9.4) | 6.1 (5.0–7.0) | 0.18 | |

| Lymphocyte count, ×10 |

1.5 (1.2–2.2) | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.5 (1.3–2.4) | 0.56 | |

| hs-cTnI, ng/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.002 (0.002–0.009) | 0.005 (0.002–0.027) | 0.002 (0.002–0.005) | 0.12 | |

| NT-pro BNP, pg/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 96.1 (18.2–256.0) | 206.0 (116.0–1098.0) | 36.2 (16.9–75.3) | ||

| MYO, ng/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 33.8 (23.6–49.8) | 48.5 (22.7–92.2) | 27.6 (23.1–41.2) | 0.21 | |

| CK-MB, U/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 1.3 (0.5–2.9) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.13 | |

| CRP, mg/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 3.7 (2.1–5.7) | 5.7 (4.7–9.7) | 2.1 (1.5–2.3) | ||

| Creatinine, mg/dL, median (Q1–Q3) | 65.2 (56.6–79.4) | 66.1 (62.0–114.1) | 58.2 (50.8–74.5) | 0.06 | |

| D-dimer, µg/mL, median (Q1–Q3) | 0.4 (0.2–3.2) | 2.9 (0.7–4.8) | 0.2 (0.2–0.5) | 0.03* | |

| ALT, IU/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 25.0 (14.0–40.0) | 26.0 (13.0–36.5) | 21.5 (14.8–53.8) | 0.82 | |

| Albumin, g/L, median (Q1–Q3) | 45.3 (40.1–46.5) | 43.6 (35.4–45.6) | 45.9 (45.2–48.1) | 0.02* | |

| Echocardiography on admission | |||||

| LVEDD, mm, mean |

47.6 |

50.3 |

45.2 |

0.01* | |

| LVEF, %, mean |

64.3 |

61.3 |

63.0 |

||

AVB, atrioventricular block; BMI, body mass index; WBC, white blood cell; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; NT-pro BNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; MYO, myoglobulin; CK-MB, creatine kinase; CRP, C-reactive protein; ALT, alanine transaminase; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic diameter; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SD, standard deviation; ECG, electrocardiogram. * indicates statistically significant; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

All 17 COVID-19-related AVB patients received dual-chamber pacemaker

implantation. Atrial leads were all placed in the right atrial appendage,

ventricular leads were implanted at the left bundle branch area (10 patients) and

right ventricular septum (7 patients). No complication occurred during procedure.

The intrinsic QRS duration was 112.8

At implantation, sensed and paced atrioventricular intervals were programmed as

170 and 200 ms for standardization. The mean threshold, impendence, and sense of

ventricular leads were 0.5 mV, 578.6

We obtained 8895 peptides in total, with an average number ranging from 5492 to 5815.2 in COVID-19-related AVB patients and controls. We quantified and mapped these peptides to corresponding protein sequences with the MaxQuant software package [12]. We identified 397 human proteins, with an average range ranging from 293 to 312.3.

To ensure the quality and reliability of the proteomic data, we analyzed the

protein mutually found in

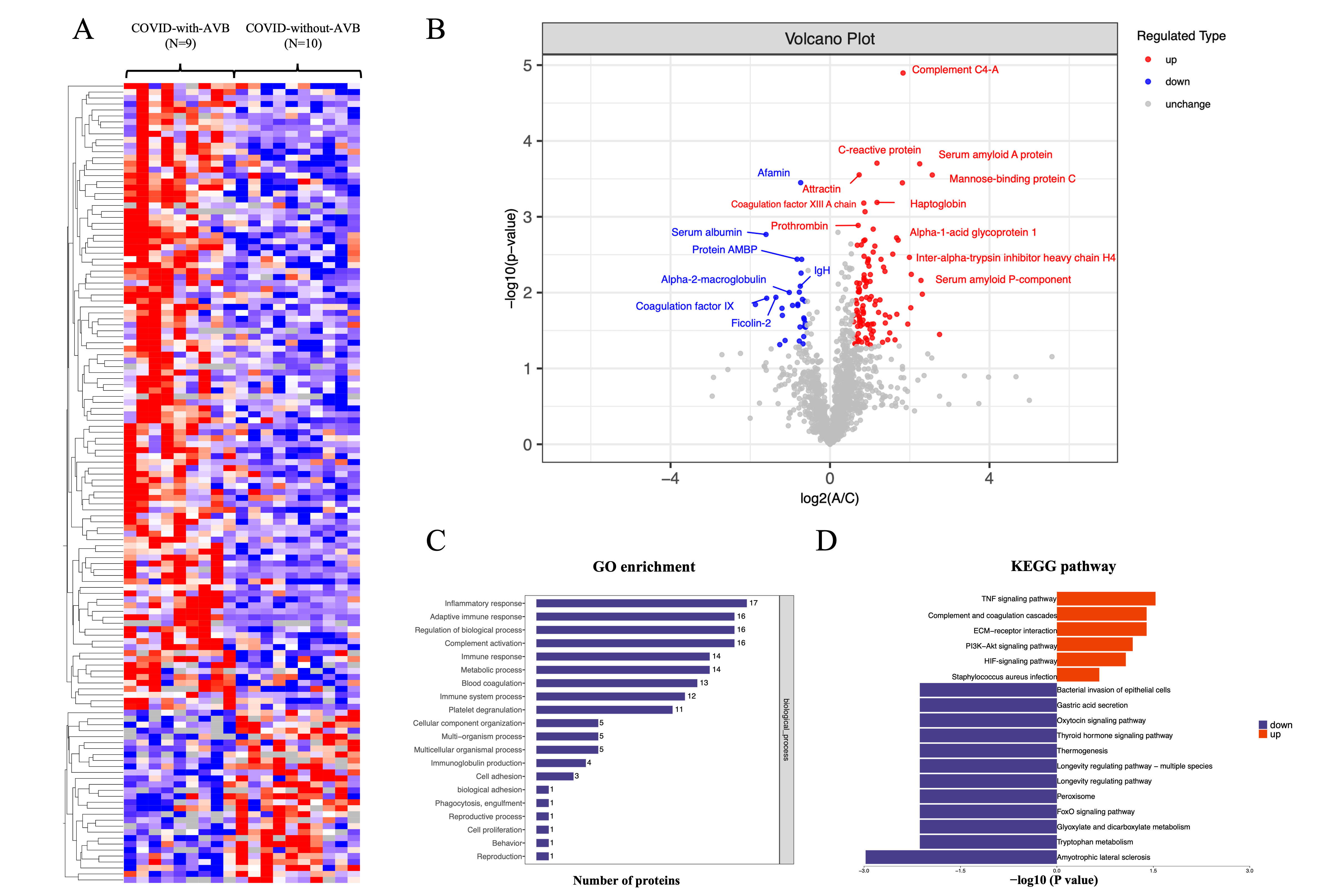

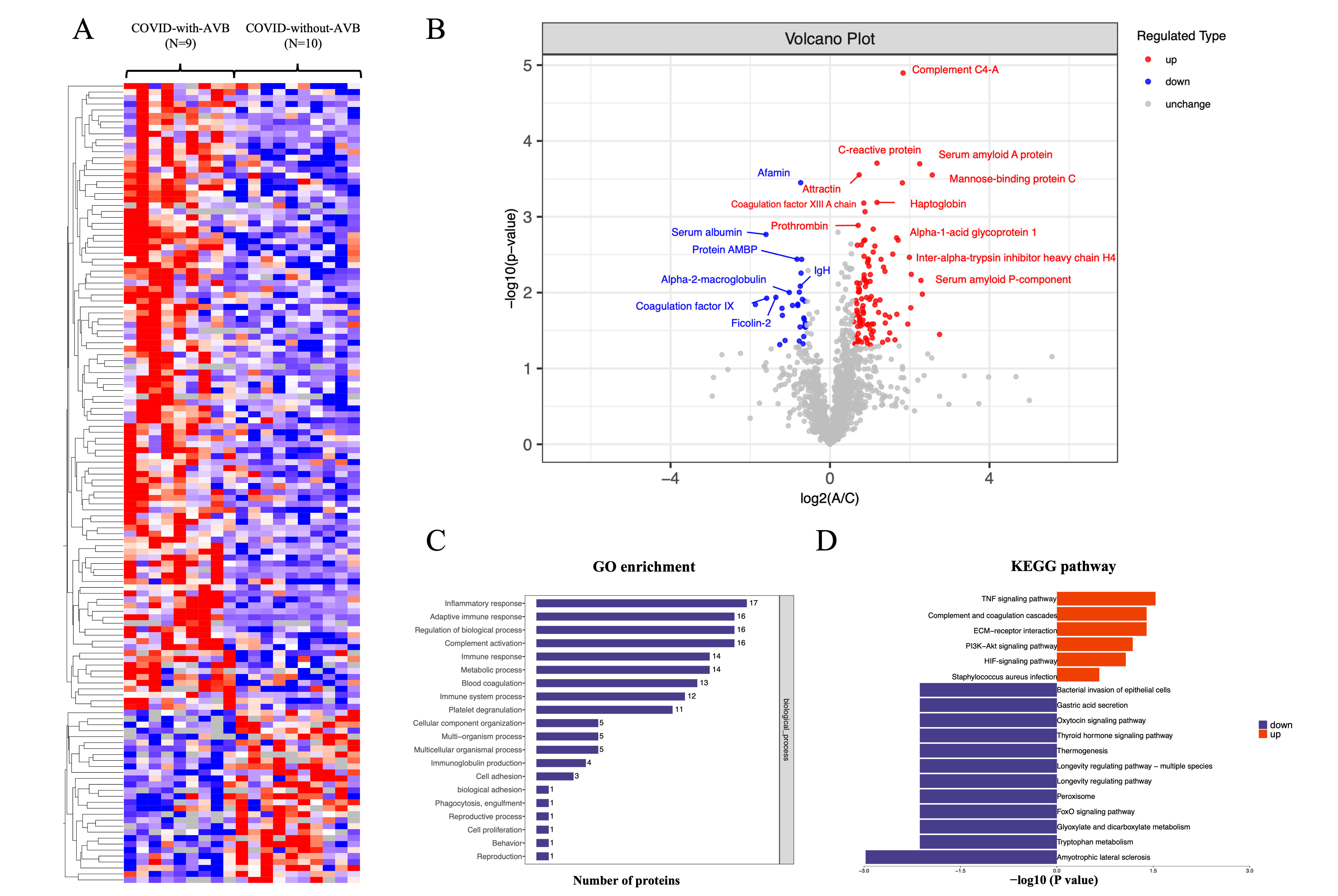

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Summary of comparative proteomics analysis of COVID-19-related AVB patients and controls. (A) The heatmap of the quantified peptides and proteins in the 19 plasma samples. (B) The volcano map of the reserved proteins in the plasma samples. (C) GO-based enrichment analysis of differential proteins of the COVID-with-AVB group and COVID-without-AVB group. (D) KEGG-based enrichment analysis of differential proteins of the COVID-with-AVB group and COVID-without-AVB group. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; AVB, atrioventricular block; GO, gene ontology; KEGG, kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes; Ig, immunoglobulin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; ECM, extracellular matrix; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; AMBP, alpha-1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor; IgH, immunoglobulin heavy chain; PI3K-Akt, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; FoxO, forkhead box O.

We analyzed the difference in plasma proteins to explore the signature of

COVID-19-related permanent AVB. The definition of significant fold changes (FC)

was

The inflammatory response obtained the highest enrichment ratio scores in the KEGG and GO analyses between the COVID-with the AVB group and COVID-without the AVB group. Moreover, the proteins involved in these processes were substantially altered in three groups. These results were consistent with clinical data that the C-reactive protein showed a significant difference in the COVID-19-with the AVB group and COVID-19-without the AVB group. These findings indicated that coagulation cascades and platelet dysfunction are the consequence of COVID-19, and inflammatory disorder might contribute to the pathogenesis of COVID-19-related AVB.

In addition to proteins related to the inflammatory response and complement and coagulation cascades, we also identified several alterations to host proteins. The plasma level of tetranectin, haptoglobin, neutrophil defensin 3, and fibrinogen beta chain were significantly elevated in the COVID-19-related AVB group. Tetranectin and haptoglobin are associated with platelet degranulation. Tetranectin enables calcium ion binding activity and cellular response to transforming growth factor beta stimulus related to the acute-phase response and viral receptor activity [13]. Haptoglobin functions to bind free plasma hemoglobin, which plays a role in modulating many aspects of the acute phase response and has antibacterial activity [14]. Neutrophil defensin 3 is a cytotoxic peptide of the innate immune system involved in reaction to bacteria, fungi, and viruses [15]. The Fibrinogen beta chain is the beta component of fibrinogen and may facilitate the immune response via innate and T-cell-mediated pathways [16]. These plasma proteins imply the potential activation of platelet degranulation and immune response to COVID-19 infection.

We identified that protein alpha-1-microglobulin/bikunin precursor (AMBP) and alpha-2-macroglobulin levels were substantially reduced in the COVID-19-with the AVB group. Protein AMBP is a complex glycoprotein that is an effector molecule in regulating inflammatory processes [17, 18]. Alpha-2-macroglobulin is a cytokine transporter and protease inhibitor of inflammatory cytokines and cascades [19, 20]. Therefore, the reduction of these anti-inflammatory proteins may intensify the inflammatory response.

COVID-19 is a multisystem disease that predominantly influences the respiratory system. However, cardiovascular manifestations including myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and heart failure are not rare [21, 22, 23]. Patients with COVID-19 are at risk for certain arrhythmias, including heart rate–corrected QT interval (QTc) prolongation, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardias, and conduction system diseases. Though the incidence of COVID-19-related conduction system diseases is lower than tachycardias, they have been demonstrated to be independent drivers of mortality and adverse events. By retrospectively analyzing 756 patients with COVID-19, McCullough et al. [24] reported atrial fibrillation and flutter occurred in 5.6%, atrioventricular block in 2.6%, and intraventricular conduction block in 11.8%. They concluded that a right bundle branch block or intraventricular block (odds ratio = 2.61, p = 0.002) increased the odds of mortality. Moreover, Pavri et al. [25] revealed that abnormal PR prolongation was associated with an increased risk of endotracheal intubation and death.

The prevalence of COVID-19-related AVB has yet to be well established. In patients hospitalized with COVID-19, studies have reported new-onset AVB occurred in 0.02–11.8% in different study populations [4, 26, 27]. Coromilas et al. [26] retrospectively analyzed patients hospitalized with COVID-19 infection worldwide, and reported the incidence of AVB is 0.02%. Among generalized hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Lao et al. [27] and Antwi-Amoabeng et al. [4] reported that the incidence of AVB was 3.6% and 11.8%. In symptomatic COVID-19 cases, Kunal et al. [23] revealed 5 AVB cases (4.6%) in 109 patients. Our study retrospectively included 72 hospitalized patients with AVB from November 2022 to March 2023 and reported 17 patients with new-onset AVB associated with COVID-19.

The molecular insights for the pathogenesis of COVID-19-related AVB remain to be

clarified. Several hypotheses have been proposed, including cytokine storm,

direct viral injury, and hypoxia. SARS-CoV-2 infection can induce an increased

systemic inflammatory response and cytokine storm manifested by an acute

elevation of serum Interleukin-6 (IL-6), Interleukin-1 (IL-1), tumor necrosis

factor-

Comparative proteomics analysis revealed altered proteins that are highly enriched in the inflammatory response. For instance, plasma levels of serum amyloid A protein, C-reactive protein, Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1, mannose-binding protein C, haptoglobin, and attractin were significantly elevated in the COVID-19-related AVB group. Among them, serum amyloid A protein, C-reactive protein, Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein 1, and mannose-binding protein C are acute-phase proteins that are closely related to infection and inflammation. C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A protein were also identified to be significantly elevated in previously reported COVID-19 patients [32]. C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A protein are major acute phase proteins in controlling and propagating the acute phase response. Emerging evidence indicates systemic inflammation can negatively influence autonomic function and atrioventricular conduction. Haarala et al. [33] demonstrated that reduced heart rate variability is associated with elevated C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A protein. Lazzerini et al. [28] found that atrioventricular conduction indices are increased with elevated C-reactive protein levels and are rapidly normalized in association with the reduction of inflammatory markers. Such findings corresponded with the clinical fingdings and lab results, which indicated AVB may be the sequelae of myocarditis. Blood tests from myocarditis patients often show elevated cardiac enzymes as troponin and inflammatory markers as C-reactive protein, lactate, and procalcitonin [2]. The median level of hs-cTnI and NT-pro BNP of COVID-19-relatedAVB is significantly higher than controls, which is supportive for diagnosing COVID-19-related myocarditis. Whether those acute-phase proteins are pivotal to the development of AVB in COVID-19 patient needs to be further elucidated.

SARS-CoV-2 may cause direct injury to the cardiac conduction system via the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor. Cardiomyocyte entry of SARS-CoV-2 may depend on binding the viral spike proteins to ACE2 receptors and on S protein priming by proteases. ACE2 receptors are abundant in the kidney and heart. Moreover, evidence shows ACE2 receptors be located in the cardiac conduction system [34]. Han et al. [8] revealed SARS-CoV-2 can infect primary pacemaker cells in the heart and induce ferroptosis that lead to arrhythmias. Vaduganathan et al. [9] demonstrated that angiotensin II is accumulated via virus-associated down-regulation of ACE2, resulting in adverse myocardial remodeling and arrhythmogenicity.

The majority of the literature documented that COVID-19-related AVB were transient and self-limiting. Dagher et al. [35] reported 4 patients developing a transient high-degree AVB during hospitalization, with 1 patient being implanted with a temporary pacemaker. After 10–21 days from admission, all patients were discharged in sinus rhythm and a normal PR interval. The spontaneous resolution of COVID-19-related AVB reveals the nature of the viral infection. However, cases of permanent AVB patients requiring paroxysmal or permanent pacing have been well reported. In our study, 8 paroxysmal AVB with symptomatic manifestations of bradycardia had permanent pacemaker implantation. Sensed and paced atrioventricular intervals were programmed as 170 and 200 ms to stimulate intrinsic conduction. After a mean follow-up of 2.9 months, the median VP ratio was 99.8%, which reveals the potential long-term damage to the conduction system. Therefore, the long-term follow-up of symptomatic AVB patients with spontaneous resolution is necessary.

We successfully performed left bundle branch area pacing (LBBAP) and right ventricular septal paing (RVSP) in all COVID-19-related AVB patients. No procedural-related complication occurred. The pacing parameters, including threshold, sense, and impendence remained stable at follow-up. Such finding indicated LBBAP and RVSP are both safe and effective to treat COVID-19-related AVB.

Our study has several limitations inherent to the design. The single-center nature of our study may potentially limit the sample size and introduce selection bias. Our study recruited hospitalized AVB patients associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection which lacks the confidence to demonstrate the causal relationship between AVB and COVID-19. However, based on Hill’s Criteria, we observed the temporal order of COVID-19 and the onset of AVB and carried out lab tests to exclude other potential viral causes besides SARS-CoV-2 in our cohort. Moreover, our study is consistent with other cross-sectional studies [4, 26, 27], case report [35], and review [5], which demonstrate the analogy and plausibility of AVB and COVID-19. Based on Han’s study [8], we believe it is reasonable to assume AVB may be the sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Additionally, most serum samples were collected from the patients in the late period of the disease, thus limiting the proteomic profiling of the acute phase. Our research also lacked a large independent cohort to validate the potential biomarkers. Despite these limitations, we believe our research uncovers important knowledge pertaining to COVID-19-related AVB. Further studies are necessary for further proteomic validation and the detailed pathogenesis of COVID-19-related AVB.

Our study depicts the clinical characteristics and concludes both LBBAP and RVSP are safe and effective to treat COVID-19-related AVB. We provides a valuable resource of proteomics profile in which several differential expressed proteins (Serum amyloid A protein, Tetranectin, Neutrophil defensin 3) enriched to inflammatory response, complement and coagulation cascades, and immune response. Our results sheds light on identifying the potential biomarkers and pathogenesis of COVID-19-related AVB.

The data regarding personal information is subjected to legal restriction of Chinese legislation. The request to access the data can be granted or rejected by State Key Laboratory of Cardiovascular Disease, Fuwai Hospital, National Center for Cardiovascular Diseases, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. YG collected the data and wrote the manuscript. KPC conceptualized the study, verified the data and revise the manuscript critically. ZLC and SJW performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. RHC, YD, and SZ did the data validation and revise the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the study and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Fuwai Hospital Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2022-ZX031). We obtained informed consent from all participants.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2022-I2M-C&T-B-049) and Beijing municipal science and technology commission (Z191100006619120).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.