1 Department of Cardiology, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Nantong University, 226001 Nantong, Jiangsu, China

2 Department of Cardiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, 210029 Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

3 Department of Cardiology, Children's Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, 210093 Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Premature ventricular complex (PVC) induced cardiomyopathy (PVC-CMP) and exacerbated left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) are common in clinical scenarios. However, their precise risk factors are currently unclear.

We performed a systematic review of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Chinese-based literature database (CBM) to identify observational studies describing the factors associated with PVC-CMP and post-ablation LVSD reversibility. A total of 25 and 12 studies, involving 4863 and 884 subjects, respectively, were eligible. We calculated pooled multifactorial odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each parameter using random-effects and fixed-effects models.

The results showed that 3 independent risk factors were associated with PVC-CMP: being asymptomatic (OR and 95% CI: 3.04 [2.13, 4.34]), interpolation (OR and 95% CI: 2.47 [1.25, 4.92]), and epicardial origin (epi-origin) (OR and 95% CI: 3.04 [2.13, 4.34]). Additionally, 2 factors were significantly correlated with post-ablation LVSD reversibility: sinus QRS wave duration (QRSd) (OR and 95% CI: 0.95 [0.93, 0.97]) and PVC burden (OR and 95% CI: 1.09 [0.97, 1.23]).

the relatively consistent independent risk factors for PVC-CMP and post-ablation LVSD reversibility are asymptomatic status, interpolation, epicardial origin, PVC burden, and sinus QRS duration, respectively.

Keywords

- premature ventricular complexes

- left ventricular systolic dysfunction

- risk factors

- meta-analysis

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) often coexist in clinical practice. Until 2016, PVC was recognized as a reversible cause of dilated cardiomyopathy, known as PVC-induced cardiomyopathy (PVC-CMP) [1]. Despite numerous efforts to investigate predictors of PVC-CMP [2, 3, 4, 5], it remains challenging to differentiate PVC-CMP from other types of dilated cardiomyopathy complicated by frequent PVC. Furthermore, it is unclear why some patients with frequent PVC develop cardiomyopathy while others do not [6, 7, 8]. Identifying which patients and when PVC elimination is needed to promote cardiac reverse remodeling, which remains an unresolved issue. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the risk factors for PVC-CMP and the reversibility of LVSD following ablation, with or without a definitive etiology.

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis following the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) protocol [9] throughout the study’s design, implementation, analysis, and reporting. We did not find related randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available at the time, so we did not register the study.

We systematically searched 3 English-based literature databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science) and 1 Chinese-based literature database (CBM) for cross-sectional studies, case-control studies, and cohort studies from January 1990 to July 2021. We used subject headings (MeSH and Emtree) and text words related to PVC and LVSD. The full literature search strategy is presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Studies meeting the following criteria were eligible: (1) published in a peer-reviewed journal in English or Chinese; (2) reported correlative factors of PVC-CMP (compared with PVC patients without LVSD) or post-ablation LVSD reversibility; (3) reported odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (or provided sufficient data for calculation). We excluded studies involving cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and acute myocardial injuries, such as acute myocardial infarction, myocarditis, and Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. 2 investigators independently assessed the eligibility of each study, resolving disagreements through consensus.

Data extraction was completed by 2 investigators and checked by 2 others using pre-designed forms (Supplementary Material 2). Extracted data included the first author, year of publication, journal, study design, study location, inclusion and exclusion criteria, cohort size, multivariate analysis model, variable inclusion criteria, and OR and 95% CI for each variable and covariate included in the statistical models.

Quality assessment was carried out using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for

cohort studies [10]. 3 items about the selection, comparability, and outcome were

checked. A score of

We combined the OR and corresponding 95% CI for each variable obtained through multivariate analysis. To minimize reporting bias, we conducted meta-analyses only for factors with multifactorial risk estimates reported in more than half of the studies.

We used StataSE (version 16.0, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) to conduct

the meta-analyses (Meta forestplot) and assess potential publication bias (Meta

funnelplot). Risk estimates were calculated using the generalized least squares

method by assuming linearity of the natural log-scale ORs. Cochran’s Q statistic

and I2 statistic were used to quantify heterogeneity among included studies.

For outcomes with high heterogeneity (I2

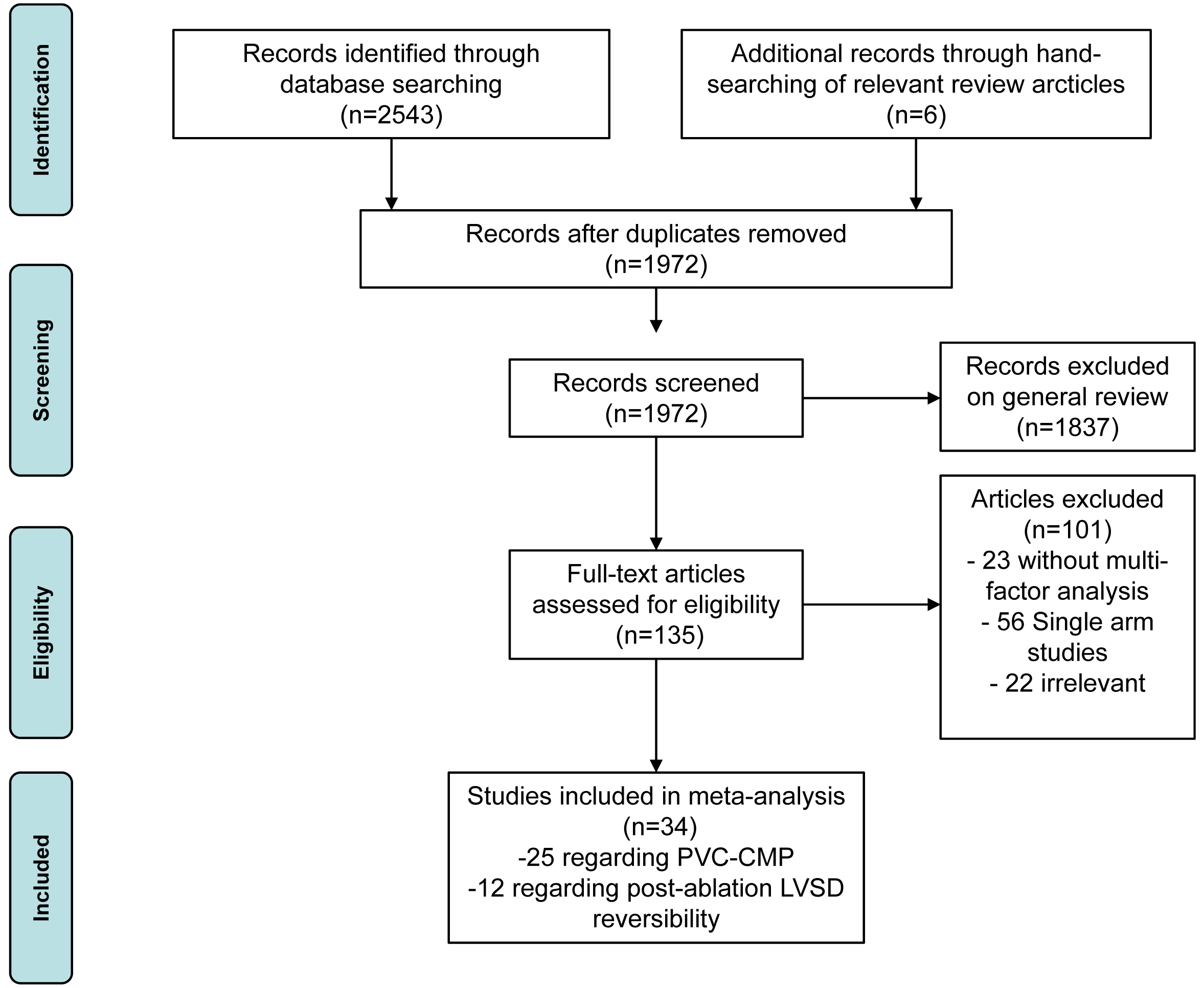

We screened 2553 articles, of which 587 duplicates and 1835 articles with titles or abstracts were excluded. After a thorough review of the remaining 97 papers, 34 articles were included for further analysis (Fig. 1). The characteristics of eligible studies are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]). Among them, 25 studies, involving 4863 subjects, focused on PVC-CMP [2, 3, 4, 5, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33], while 12 studies, involving 884 subjects, addressed factors related to post-ablation LVSD reversibility [6, 17, 26, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. PVC-CMP, premature ventricular complexes induced cardiomyopathy; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

| First author, year | Journal | Study type | Country/region | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | Cohort size | Observe events |

| Koca H, 2020 [31] | Pace-Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology | cross-sectional | Turkey | symptomatic PVCs scheduled for RFCA | SHD/PVC recurrence | 150 | LVEF |

| Krishnan B, 2017 [26] | JACC Clin Electrophysiol | cohort | America | PVC |

known cause of LVD | 61 | LVEF |

| Latchamsetty R, 2015 [3] | JACC Clin Electrophysiol | retrospective cohort | America; Germany | RFCA for frequent idiopathic PVCs | prior infarcts or delayed enhancement identified by CMRI | 1185 | LVEF |

| Lee A, 2019 [29] | Heart Lung Circ | retrospective cohort | Australia | patients for ablation of PVCs | with pre-existing scar substrate | 152 | LVEF |

| Mao J, 2021 [33] | Sci Rep | retrospective cohort | America | undergone PVCs ablation | CAD/VHD/ARVC and cardiac sarcoidosis | 51 | LVEF |

| Niwano S, 2009 [14] | Heart | prospective cohort | Japan | frequent OT PVCs ( |

any detectable heart disease | 239 | ∆LVEF |

| Olgun H, 2011 [16] | Heart Rhythm | cross section | America | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | / | 51 | LVEF |

| Park KM, 2017 [4] | Int J Cardiol | Bidirectional cohort | Korea | symptomatic frequent PVCs ( |

SHD | 144 | LVEF |

| Parreira L, 2019 [30] | Cardiology Research | retrospective cohort | Portugal | frequent PVCs ( |

history of documented AF or AFL | 285 | HF end point |

| Sadron Blaye-Felice M, 2016 [5] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | France; Switzerland | patients referred for PVC ablation | frequent nonsustained VT | 168 | LVEF |

| Voskoboinik A, 2020 [2] | Heart Rhythm | cross section | America | PVCs (average daily burden |

SHD | 206 | LVEF |

| Yamada S, 2018 [27] | J Interv Card Electrophysiol | cross section | Taiwan | RVOT PVCs undergoing ablation | SHD/DCM | 130 | LVEF |

| Yokokawa M, 2012 [18] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | PVCs undergoing ablation | SHD | 294 | LVEF |

| Ban JE, 2013 [19] | Europace | cross section | Korea | frequent PVCs ( |

SHD | 127 | LVEF |

| Kanei Y, 2008 [13] | Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol | cross section | Japan | frequent ( |

IHD, SHD, or other cause of LVSD | 108 | LVEF |

| Billet S, 2019 [28] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | France | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | frequent non-sustained VT ( |

33 | LVEF |

| Kawamura M, 2014 [21] | J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol | prospective cohort | America | undergoing successful ablation of PVCs | other causes of cardiomyopathy | 214 | LVEF |

| Hamon D, 2016 [24] | J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol | prospective cohort | America; France | frequent PVCs ( |

/ | 102 | LVEF |

| Ghannam M, 2021 [32] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America; France | frequent PVCs referred for ablation | / | 351 | LVEF |

| Carballeira Pol L, 2014 [20] | Heart Rhythm | prospective cohort | America; France | structural or genetic heart disease | 45 | LVEF | |

| Bas HD, 2016 [23] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | SHD | 107 | LVEF |

| Deyell MW, 2012 [17] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | patients with successful ablation of PVCs | / | 103 | LVEF |

| Yifan Mu, 2015 [22] | Cardiovascular & PulmonaryDisease | retrospective cohort | China | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | multifocal PVC; SHD; other cause of LVD | 287 | LVDD normalized after ablation |

| Liyun Zhang, 2016 [25] | CHINA MODERN MEDICINE | retrospective cohort | China | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | SHD; other cause of LVD | 96 | LVEF normalized to |

| Baman TS, 2010 [15] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | frequent PVCs referred for catheter ablation | CAD | 174 | LVEF |

| Koca H, 2020 [31] | Pace-Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology | cohort | Turkey | symptomatic PVCs scheduled for RFCA | SHD/PVC recurrence | 39 | LVEF normalized to |

| Krishnan B, 2017 [26] | JACC Clin Electrophysiol | cohort | America | PVC |

known cause of LVD | 31 | LVEF normalized to |

| Maeda S, 2017 [34] | J Interv Card Electrophysiol | retrospective cohort | America | PVC-CMP underwent ablation | SHD | 55 | ΔLVEF |

| Mao J, 2021 [33] | Sci Rep | retrospective cohort | America | PVC-CMP undergone ablation | CAD/VHD/ARVC and cardiac sarcoidosis | 19 | ΔLVEF |

| Mountantonakis SE, 2011 [6] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | frequent PVCs ( |

/ | 69 | ΔLVEF |

| Penela D, 2015 [35] | Heart Rhythm | prospective cohort | Spain; Argentina | frequent PVC ( |

survivors of SCD, sustained VT or syncope, previous ICD, or diagnosis of ARVC | 66 | removing the PP-ICD indication |

| Penela D, 2020 [36] | Europace | prospective cohort | Spain; Italy; Romania | frequent PVCs ( |

/ | 215 | improvement of at least 5 absolute points in LVEF |

| Penela D, 2017 [37] | Heart Rhythm | prospective cohort | Spain; Argentina | frequent PVCs ( |

SHD | 81 | improvement of at least 5 absolute points in LVEF |

| Penela D, 2013 [38] | J Am Coll Cardiol | prospective cohort | Spain; Argentina; Netherlands | frequent PVCs ( |

/ | 80 | improvement of at least 5 absolute points in LVEF |

| Deyell MW, 2012 [17] | Heart Rhythm | retrospective cohort | America | underwent successful ablation of PVCs ( |

a known cause for LVD or a history of sustained VT/appropriate ICD discharges or SCD | 37 | reversible (10% increase to a final LVEF of 50%) |

| Abdelhamid MA, 2018 [39] | Indian Heart J | cohort | Egypt | PVCCM ( |

sustained VT, CAD, atrial arrhythmias, NYHA III /IV, epicardial origin of PVCs | 77 | ΔLVEF |

| Wojdyła-Hordyńska A, 2017 [40] | Kardiol Pol | retrospective cohort | Germany; Poland | symptomatic frequent PVCs refractory to medical therapy, and with LVSD | sustained VT | 109 | / |

Abbreviations: PVC, premature ventricular complex; RFCA, radiofrequency catheter ablation; SHD, structural heart disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVDD, left ventricular diastolic diameter; CMRI, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging; CAD, coronary artery disease; VHD, valvular heart disease; ARVC, arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; AF, atrial fibrillation; AFL, atrial flutter; VT, ventricular tachycardia; PP-ICD, primary prevention (PP) implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD); PVC-CMP, premature ventricular complex (PVC) induced cardiomyopathy; SCD, sudden cardiac death; LVD, left ventricular dysfunction; HF, heart failure; OT, outflow tractc; RVOT, right ventricle outflow tract; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; IHD, ischemic heart disease; LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

For PVC-CMP, 19 studies were designed as cohort studies

(prospective/retrospective) with a follow-up time of 14–100 months and 6 studies

were cross-sectional [2, 13, 16, 19, 27, 31]. Studies were located in

Europe [3, 5, 20, 24, 28, 30, 31, 32], America [2, 3, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 32, 33], Asia [4, 13, 14, 19, 22, 25, 27] and Australia [29], and 10

developing countries, 10 developed countries and 5 multicenter studies [3, 5, 20, 24, 32]. Most of the 25 studies included symptomatic frequent PVC patients

referred for catheter ablation other than 2 [2, 30]. A total of 7 did not

emphasize the exclusion of the structural heart disease (SHD) [5, 16, 17, 24, 28, 30, 32]. The reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (

12 cohort studies from America [6, 17, 26, 33, 34, 37, 38], Europe [35, 36, 37, 38, 40], Egypt [39] and Turkey [31] explored the characteristics of patients who obtained complete or partial cardiac function restoration after PVC ablation after the 4–18 month follow-ups. 5 studies [6, 35, 36, 38, 39] incorporated coronary heart disease (CHD). The evaluation criteria for cardiac function reversibility was LVEF normalization [17, 26, 31, 40], LVEF increased by more than 5–10% or 5 absolute points [6, 33, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39], and removing the primary prevention (PP) implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) (PP-ICD) indication [35].

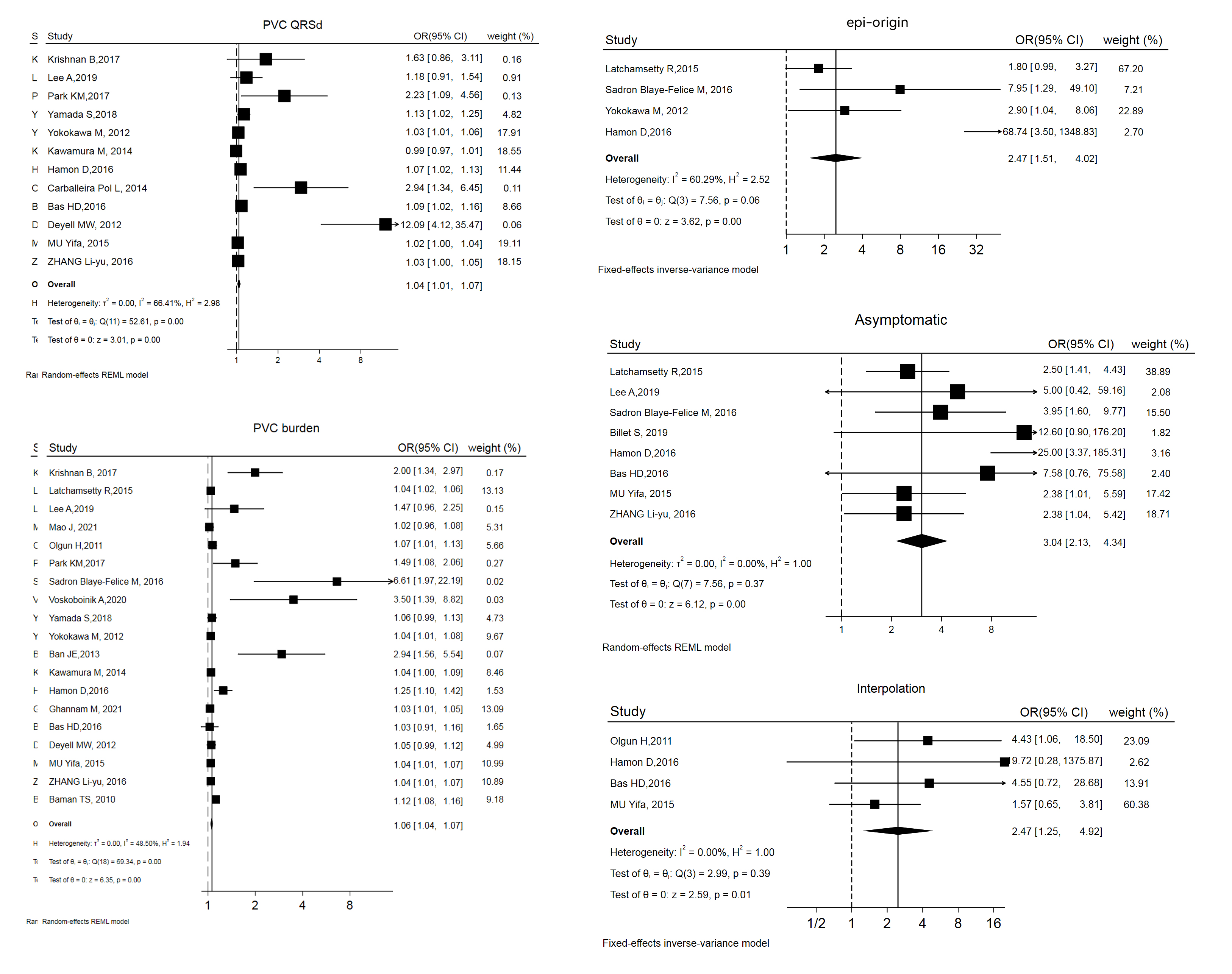

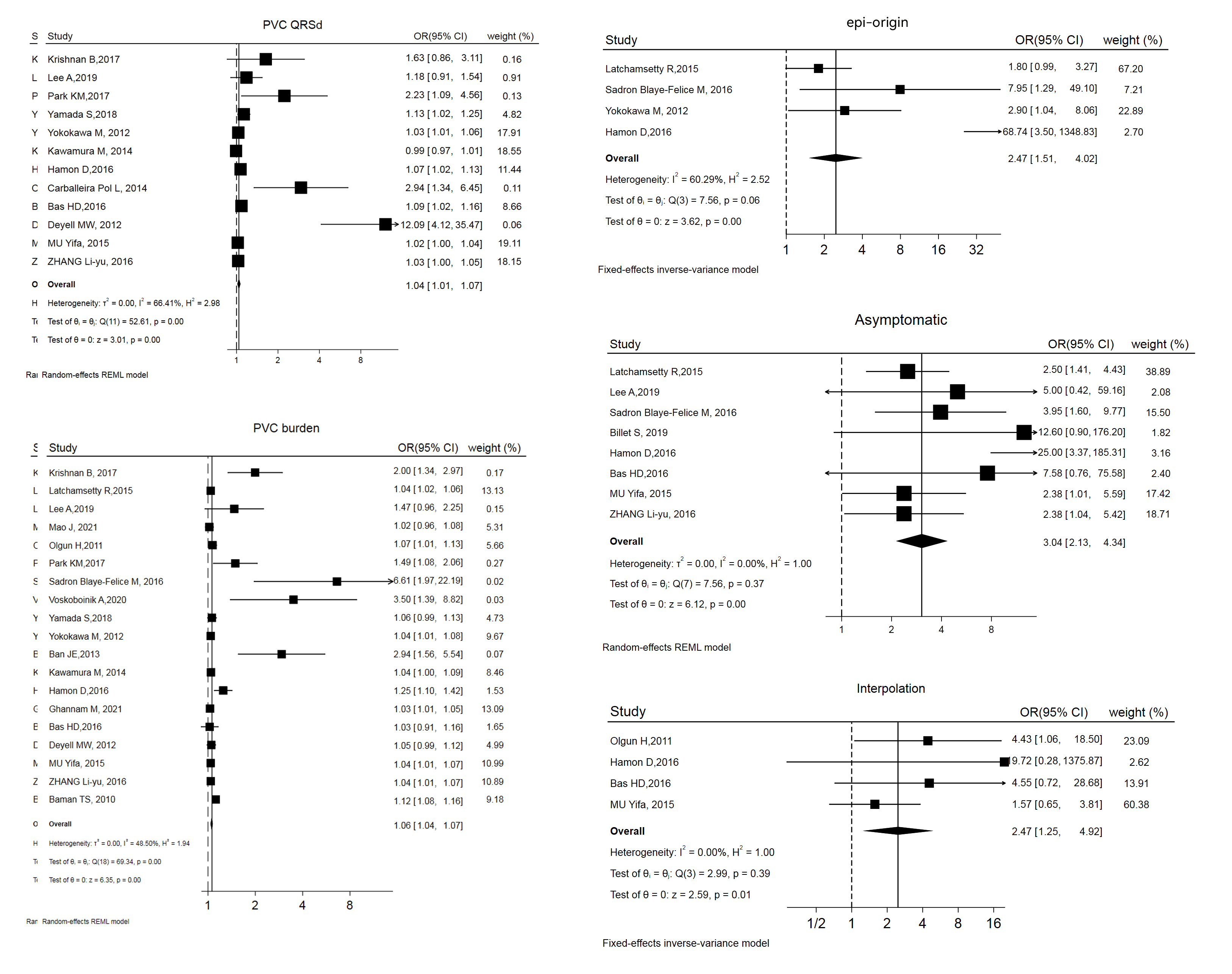

The variables and confounders are shown in Table 2 (Ref. [2, 3, 4, 5, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]). 5 of them were included in more than 1 study, with multifactorial risk estimates (OR and 95% CI) reported in more than 50% of these studies. Merging the results revealed that 3 factors were significantly related to PVC-CMP: being asymptomatic (OR and 95% CI: 3.04 [2.13, 4.34]), interpolation (OR and 95% CI: 2.47 [1.25, 4.92]), and epicardial origin (epi-origin) (OR and 95% CI: 3.04 [2.13, 4.34]). Forest plots and funnel plots are displayed in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between the 5 parameter and PVC-CMP. PVC-CMP, premature ventricular complexes induced cardiomyopathy; PVC, premature ventricular complex; QRSd, QRS wave duration; epi, epicardial; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

| First Author, Year | Age | Sex: male | Asymptomatic | PVC burden | PVC QRSd | PVC CI | LV-originated | Epi-originated | Single PVC | Ns-VT | RVOT | Interpolation | Inclusion | Others |

| Koca H, 2020 [31] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Smoker; DM; NT-proBNP; AAD | |||||

| Krishnan B, 2017 [26] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

BMI; CAD; CHF; AAD | |||||

| Latchamsetty R, 2015 [3] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | p |

CAD; HTN; AAD |

| Lee A, 2019 [29] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | p |

BMI; Scar; Smoker; CAD; AF; AAD | |||

| Mao J, 2021 [33] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | fixed | LV GLS; Scar; AAD |

| Niwano S, 2009 [14] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | / | Basal LVEF; AAD | |||

| Olgun H, 2011 [16] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | p |

AAD | ||

| Park KM, 2017 [4] | ⚫ | N/A* | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

HTN; AAD; Sinus QRSd | |||

| Parreira L, 2019 [30] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | Fixed | CAD; HTN; DM; PAC; AAD | ||

| Sadron Blaye-Felice M, 2016 [5] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

AAD; Sinus QRSd | |||||

| Voskoboinik A, 2020 [2] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | p |

BMI; CAD; HTN; Superior axis; AAD | ||||||

| Yamada S, 2018 [27] | N/A | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

PDI; AAD | |||||

| Yokokawa M, 2012 [18] | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

AAD | |||

| Ban JE, 2013 [19] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | p |

Retrograde P-wave; AAD | |||||||

| Kanei Y, 2008 [13] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A* | N/A | fixed | Mean HR; AAD | ||||

| Billet S, 2019 [28] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | p |

AAD | |||||||||

| Kawamura M, 2014 [21] | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

BMI; AAD | ||||

| Hamon D, 2016 [24] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | p |

SHD; AAD; Sinus QRSd | |

| Ghannam M, 2021 [32] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Scar; AAD; Sinus QRSd | |||||

| Carballeira Pol L, 2014 [20] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | p |

AAD | ||||||

| Bas HD, 2016 [23] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | p |

Variation; AAD | |

| Deyell MW, 2012 [17] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

AF; AAD; Sinus QRSd | |||||||

| Yifan Mu, 2015 [22] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A* | N/A | ⚫ | fixed | Superior axis; course of disease | ||||

| Liyun Zhang, 2016 [25] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | fixed | Mean HR; course of disease | ||

| Baman TS, 2010 [15] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

/ | ||||||

| Yield (%) | 12.0 | 28.0 | 57.1 | 79.2 | 66.7 | 46.1 | 38.5 | 50.0 | 30.0 | 44.4 | 40.0 | 57.1 | / | / |

Abbreviations: PVC, premature ventricular complex; QRSd, QRS wave duration; CI, coupling interval; epi, epicardial; Ns-VT, non-sustained ventricular tachycardia; RVOT, right ventricle outflow tract; DM, diabetes mellitus; AAD, anti-arrhythmic drugs; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; HTN, hypertension; AF, atrial fibrillation; LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PAC, premature atrial complex; PDI, peak deflection index; HR, heart rate; SHD, structural heart disease.

Annotations: ⚫ indicates that the

variable included in the model and with the odds ratios (OR) provided;

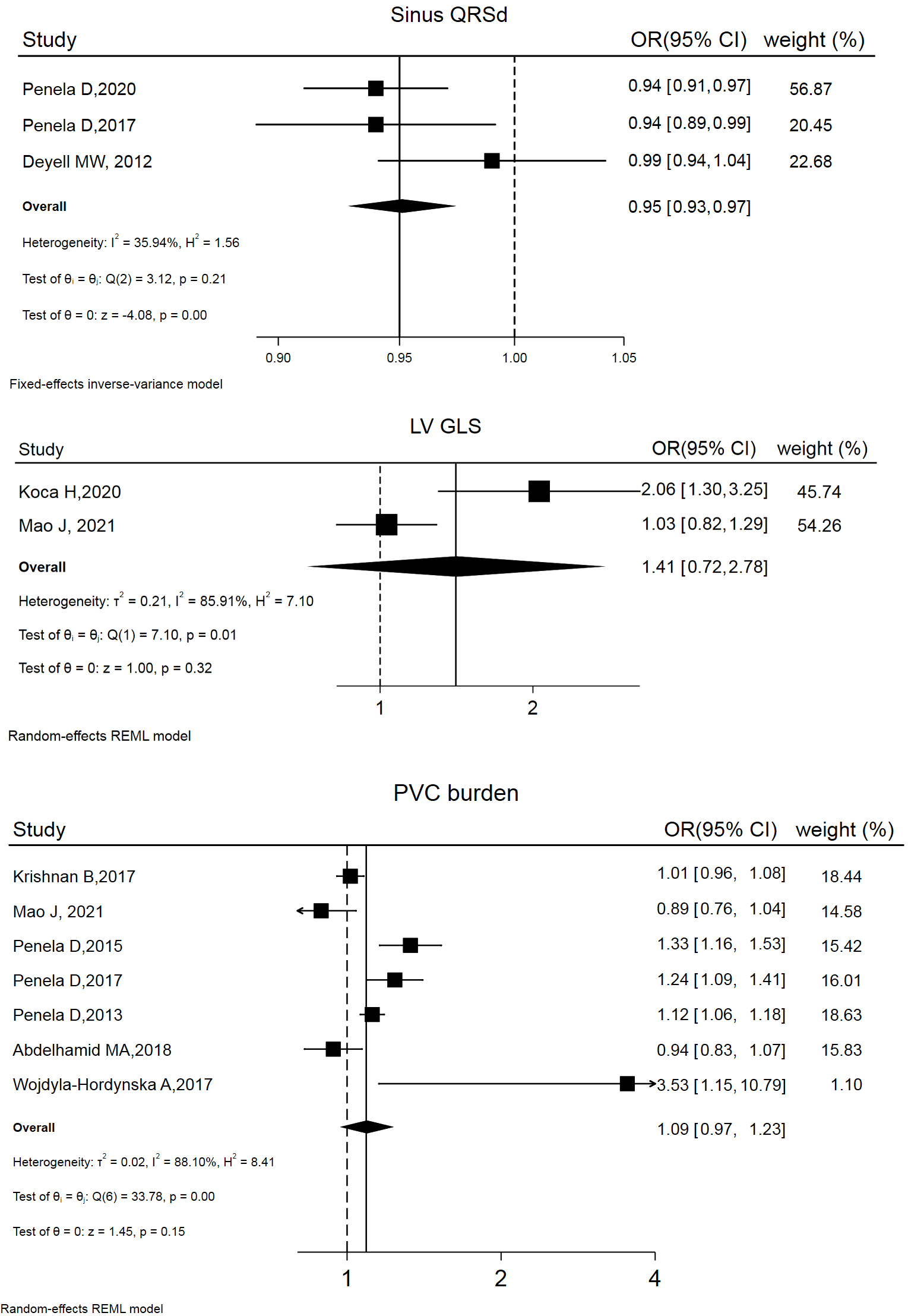

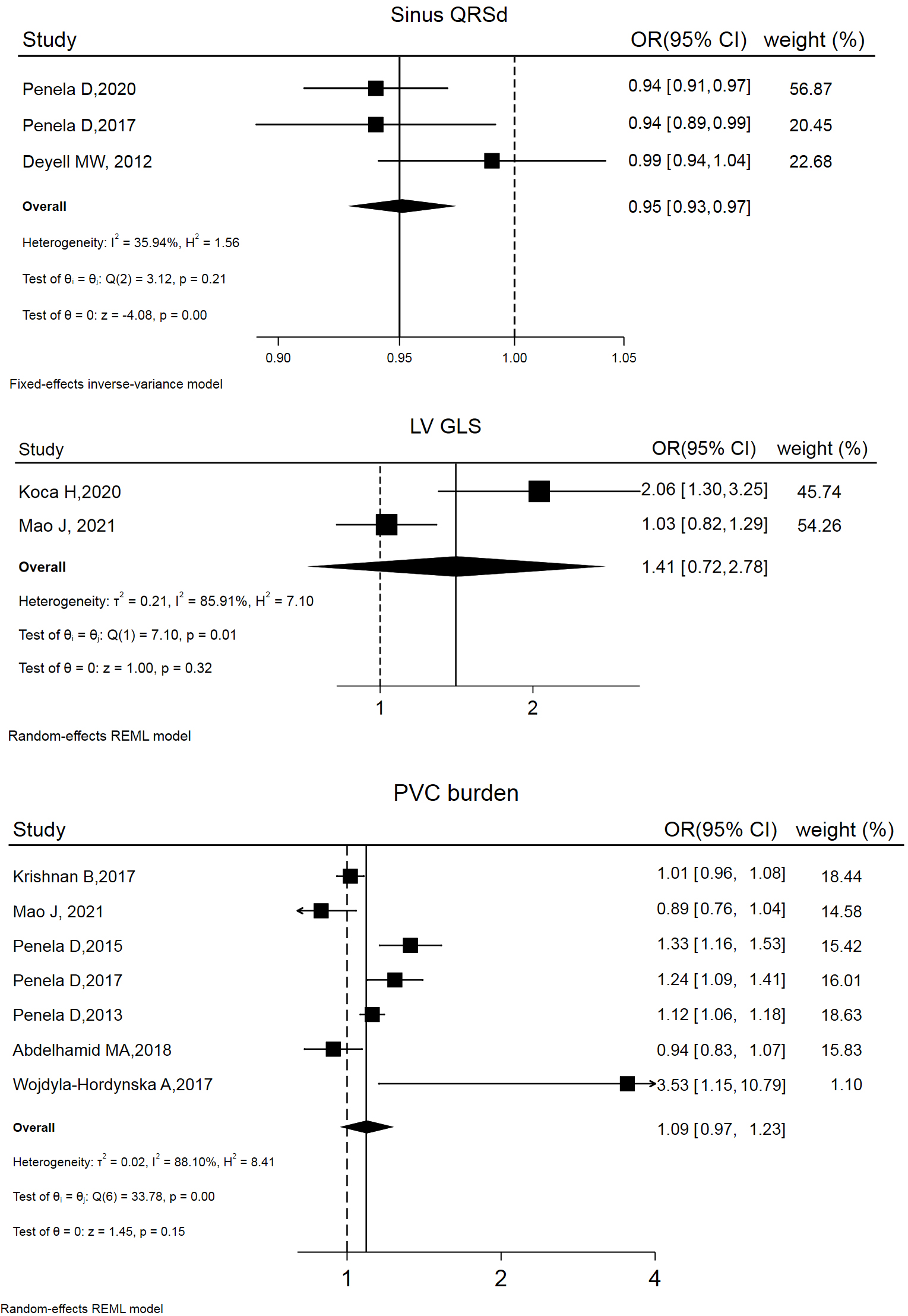

12 studies addressed LVSD reversibility. Factors involved in models predicting post-ablation LVSD reversibility are summarized in Table 3 (Ref. [6, 17, 26, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]). The risk estimates (OR and 95% CI) of 3 variables were combined, yielding the following results: left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV GLS) (OR and 95% CI: 1.41 [0.72, 1.78]), PVC burden (OR and 95% CI: 1.09 [0.97, 1.23]), and sinus QRS wave duration (QRSd) (OR and 95% CI: 0.95 [0.93, 0.97]). Forest and funnel plots are displayed in Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the association between the 3 parameter and post-ablation LVSD reversibility. LVSD, left ventricular systolic dysfunction; PVC, premature ventricular complex; QRSd, QRS wave duration; LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

| First Author, Year | Basal LVEF | PVC burden | PVC QRSd | Sinus QRSd | PVC CI | Single PVC | LV GLS | Inclusion criteria | Others |

| Koca H, 2020 [31] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | p |

Age; NT-proBNP; LVDD | ||

| Krishnan B, 2017 [26] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | p |

BMI; Asymptomatic; CHF; CAD; LV-originated; AAD | ||

| Maeda S, 2017 [34] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); HTN; AAD |

| Mao J, 2021 [33] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | ⚫ | ⚫ | Fixed | Sex (male); Age; NT-proBNP; LV-originated; AAD |

| Mountantonakis SE, 2011 [6] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); Age; Cardiomyopathy; LV-originated | |||

| Penela D, 2015 [35] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); Age; CAD; LV-originated | |

| Penela D, 2020 [36] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); Age; SHD; LV-originated | |||

| Penela D, 2017 [37] | ⚫ | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); Age; NT-proBNP; Scar; LV-originated | |||

| Penela D, 2013 [38] | N/A | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Sex (male); Age; SHD; Scar; epi-origin; LV-originated | |

| Deyell MW, 2012 [17] | ⚫ | ⚫ | ⚫ | p |

Age; Asymptomatic; CHF; AAD | ||||

| Abdelhamid MA, 2018 [39] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | / | Asymptomatic; SHD; epi-origin; LV-originated | |

| Wojdyła-Hordyńska A, 2017 [40] | ⚫ | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | p |

Age; gender; SHD; site of origin | |

| Yield (%) | 44.4 | 77.8 | 28.6 | 100 | 33.0 | 14.3 | 66.7 | / | / |

Abbreviations: PVC, premature ventricular complex; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; QRSd, QRS wave duration; CI, coupling interval; LV GLS, left ventricular global longitudinal strain; BMI, body mass index; LVDD, left ventricular diastolic diameter; CAD, coronary artery disease; CHF, chronic heart failure; AAD, anti-arrhythmic drugs; HTN, hypertension; AF, atrial fibrillation; LV, left ventricle; SHD, structural heart disease; epi, epicardial.

Annotations: ⚫ indicates that the variable included in the

model and with the OR provided;

To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to examine the independent risk factors of PVC-CMP and post-ablation LVSD reversibility. We identified 3 elements (asymptomatic PVCs, interpolation, and epicardial origin) that can independently predict PVC-CMP and 2 parameters (PVC burden and sinus QRS duration) significantly correlated with post-ablation LVSD reversibility.

PVC burden has been reported as a predictor for PVC-CMP [2, 5, 14], but the

results have been controversial. Some studies suggested that at least a 10% PVC

burden is required to induce PVC-cardiomyopathy [15, 41], while others disagreed

[42, 43, 44]. Our meta-analysis showed that PVC burden had a weak relationship with

PVC-CMP (OR and 95% CI: 1.06 [1.04, 1.07]), but significant publication bias was

observed (Fig. 2 and Funnel plots in the Supplemental Material). Based

on the literature review and our clinical experience, we tend to believe that PVC

burden alone is not a strong risk factor for PVC-CMP. Del Carpio Munoz et al.

[45] found that PVCs originating from the right ventricle (RV) with a lower daily

burden than from the left ventricle (10% vs. 20%) resulted in LVEF impairment.

This suggests that the location of PVCs may also play a role. Another reason for

this discrepancy may be the misestimation of PVC burden by 24-hour Holter

monitoring due to its day-to-day variability. Several studies have suggested that

a PVC QRS duration

Not all patients diagnosed with PVC-CMP will benefit from PVC ablation in terms of improving cardiac function [17, 26, 34]. In cases of SHD, PVC ablation is generally considered helpful for cardiac reverse remodeling [6, 7, 8]. It appears that determining the extent and timing of PVC’s causal role in cardiomyopathy is complex, possibly dynamic. A previous meta-regression [48] and a recent systematic review [49] indicated that PVC burden, LVEF, QRS duration, the absence of underlying cardiomyopathy, younger age, variability in the frequency of PVCs, and lower left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), but not the origin of PVCs, were predictive of post-ablation LVEF improvement. According to this meta-analysis, 2 factors independently correlated with post-ablation LVEF improvement: a greater PVC burden and a narrower sinus QRS duration. Basal LVEF and concurrent SHD do not appear to be crucial. As previously mentioned, the extent to which ventricular asynchrony caused by PVCs worsens cardiac function is a key consideration in determining the benefit of PVC elimination (ablation) for cardiac resynchronization therapy. It is logical to assume that a higher PVC burden results in a greater degree of asynchrony, and a narrower sinus QRS duration indicates better synchronization achieved through PVC ablation.

The principal strength of this study lies in the systematic literature search conducted by independent reviewers who searched comprehensive medical literature databases. We extracted and combined risk estimates (OR and 95% CI) obtained through multifactorial analysis, taking publication bias into consideration. Additionally, all included studies exhibited relatively high quality.

However, this study has several limitations. First, there is considerable heterogeneity among the included studies in terms of design, inclusion criteria, and evaluation criteria. Some studies may share partial cohorts [35, 36, 37, 38]. Second, a selection bias is likely present because most studies enrolled patients referred for ablation due to frequent, symptomatic, and medical refractory PVCs. Third, despite contacting corresponding authors via email, the risk estimates (OR and 95% CI) for some variables included in the multifactorial analysis model are unavailable.

In conclusion, current studies show considerable inconsistency regarding the prediction of PVC-CMP and post-ablation LVSD reversibility. The relatively consistent independent risk factors for PVC-CMP and post-ablation LVSD reversibility are asymptomatic status, interpolation, epicardial origin, PVC burden, and sinus QRS duration, respectively.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

DZ, QZ and FZ provided the conception and designed the study and interpretation of data. QC analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. ZZ, PZ, JS, JY performed the research. QZ provided the funding. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by Nantong University School-level Fund Project (2022LZ003) and Nantong basic Science Research and Social livelihood Science and Technology Plan Project (JCZ2022007).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.rcm2509327.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.